Updated Friday, May 5, 6:55 AM London time, with comments from Sophos principal research scientist Chester Wisniewski

Since news began circulating last night of a phishing campaign parading around as Google Doc access links, the tale has taken strange twists and turns.

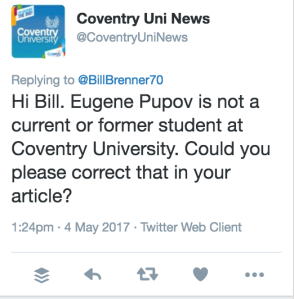

A self-described graduate student claims he was behind the blast of emails, and that they were part of a test for a school project, not a phishing attack. But according to the university he claims to be enrolled at, he’s not a student there.

Meanwhile, as the hours pass, it becomes less clear if what Google users received was truly a phishing attempt. Sophos principal research scientist Chester Wisniewski says it wasn’t, exactly:

First and foremost, this is an abuse of Google’s APIs. While at first glance it appears to be a phishing attack, the emails come from Google and you are logging into the real Google.

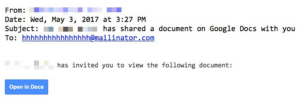

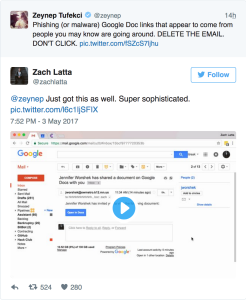

Last night, news and social media sites were ablaze with word of a new phishing campaign using fake Google Doc sharing emails to lure its prey, arriving in messages like this:

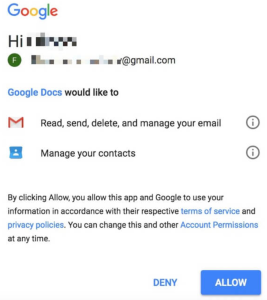

Those clicking the link got a Google login and permissions page asking that they grant the fake Docs app the ability to “read, send, delete and manage your email” as well as manage your contacts:

Rather than coming from the real Google Docs, this came from a bogus app called “Google Docs.”

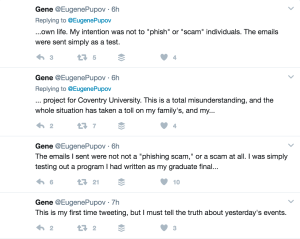

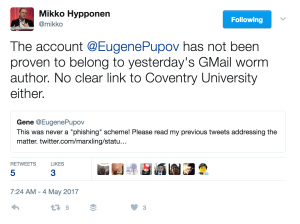

Later, someone calling himself Eugene Pupov took to Twitter claiming he sent the emails to test a program created for a graduate final. It was in no way designed as a phishing attack, he said:

Cries of phishing

At the time of writing, Pupov hadn’t returned messages seeking comment (if he responds, we’ll update this article). But his tweets expressed despair over the state of affairs. This story was carried by news outlets large and small, with ominous headlines about phishing attacks disguised as Google Doc access emails.

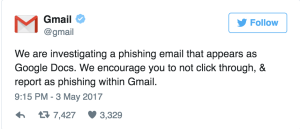

Google itself confirmed it was investigating phishing attempts last night:

Twitter was full of messages from people who received such messages. On the surface, it appears folks realized quickly that something wasn’t right with these links:

Google acted quickly, announcing steps users could take if they had indeed clicked on the link:

Wisniewski said it’s ultimately Google’s responsibility to stop these sorts of threats:

Attacks on systems that are open for anyone to sign up as a developer using OAuth have been vulnerable to this type of attack for a long time, and the onus is on Google to do a better job vetting application developers. This is no different than the abuse of the Google Play store by malware authors. There is very little individuals can do other than be forever suspicious about legitimate requests from services provided by Google, Twitter, Facebook and other online services that use OAuth with an un-vetted application developer program. Twitter’s users were attacked using these techniques a few years back. Unfortunately, Google has also fallen victim to a similar attack vector. When users see official emails from Google and official login pages used in scams, this leads the goodwill Google has garnered from its users to be potentially damaged. All providers of OAuth have a responsibility to police the use of their platforms to stop users from being tricked through official requests from services like Google, Twitter and Facebook. We do suggest that users keep an eye on social media. As the Google Doc “phishing” attempt demonstrates, Twitter is a great early-warning system. There’s little doubt that the tweeted warnings saved people from being victimized.

Is he for real?

It remains to be seen if Pupov’s claims are genuine. An email we sent to his gmail account promptly bounced back, and we’re still waiting for him to respond to our questions via Twitter. One question we have: what was the exact purpose of his project?

Other security experts, meanwhile, have pointed out that Pupov’s claims have not yet been independently verified.

According to Coventry University, he’s not registered as a student there:

What to do?

The question, after all this, is what users should do to protect themselves. If this were a cut-and-dry phishing attempt, our tips would be to:

- Be careful what you click. This one is painfully obvious, but users need a constant reminder.

- Check the address bar for the correct URL. The address bar in your web browser uses a URL to find the website you are looking for. The web address usually starts with either HTTP or HTTPS, followed by the domain name. The real websites of banks and many others use a secure connection that encrypts web traffic, called SSL or HTTPS. If you are expecting a secure HTTPS website for your bank, for example, make sure you see a URL beginning with https://before entering your private information.

- Look for the padlock for secure HTTPS websites. A secure HTTPS website has a padlock icon to the left of the web address.

- Consider using two-factor authentication for more security. When you try to log into a website with two-factor authentication (2FA), there’s an extra layer of security to make sure it’s you signing into your account.

- Keep an eye on Twitter: As the Google Doc phishing attempt demonstrates, Twitter is a great early-warning system. There’s little doubt that the tweeted warnings saved people from being victimized.

Since the details around what happened remain confused, it doesn’t hurt to take additional steps. For example, if someone believes they may have inadvertently downloaded a sketchy app, they can go to myaccount.google.com/permissions and revoke permissions for any apps they don’t trust.

Wisniewski added:

Users should check the apps they have approved to access their accounts and remove anything that may be suspicious on all OAuth-based platforms. For Google it is under your Google account -> Sign-in & Security -> Connected apps & sites. On Twitter and Facebook it is Settings & Privacy -> Apps.

John

The account Eugene Pupov on twitter was only created this month, with the first tweet being that stating it was a test. The original profile picture was associated with someone completely different, which is now not associated with the twitter profile. It is unlikely this was a test.

Bill Brenner

I share your skepticism, especially since Coventry University messaged me that he’s not really a student there.

Mahhn

Do you think the tweets were to make people less responsive to cleaning up it’s dirty work? giving the impression it might be nondestructive

Bill Brenner

That is certainly possible. Also possible is that this person was looking for attention. I doubt that, though.

Mahhn

I only know of one person that fell for this, a coworkers mate at a different employer.

Glad management gets to see the value in us blocking all public storage.

Wilderness

“Glad management gets to see the value in us blocking all public storage” That’s fantastic!

Edward

Except that google hasn’t fixed the vulnerability to completely spoof the omnibar and make the URL appear legit as well. At least the guy didn’t inject it with ransomware that would of been the most destructive attack in history I would imagine.

Keith Hanson (@keith_hanson)

This really didn’t do much at all. I know it seems like all the facts are pointing skeptically at this new user posting the story, but the code itself (my team and I dove into it after I got caught up in it) seemed amateur, rushed, and didn’t actually do much at all with the power it held.

Those facts seem to me to corroborate the student story. As for the student not being in their database – would you admit to the world under your real name as a college student? I sincerely doubt it.

John

If it were an evil person instead of a student, they have a huge number of contact lists now and a huge number of email addresses. That alone would be worth $$$$

Mario583

Mailinator is used as a spam email that can ONLY receive never send.

Paul Ducklin

The mailinator address in the worm email is the To: address, not the From:, so that address *is* receiving, not sending. You get your copy of the email via BCC.

Therefore the crook gets to keep track of how this thing is spreading.