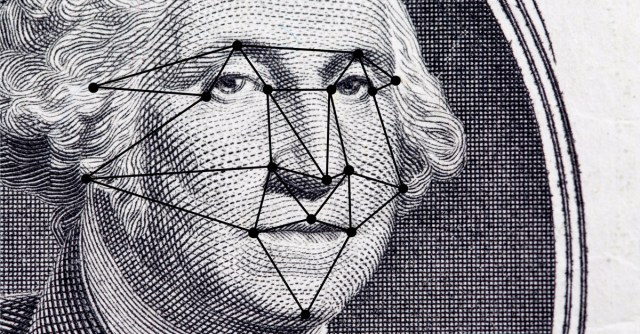

Between civil and criminal mugshot photos, the State Department’s visa and passport databases, the Defense Department’s biometric database, and the drivers’ license databases of 18 states, nearly half of all Americans are in a facial recognition database that the FBI can get at without warrants or without even having to prove they have reasonable suspicion that we’ve done anything wrong.

How did we get in there?

Illegally, that’s how. That was the assessment of last week’s House oversight committee hearing, when politicians and privacy campaigners scathingly took the FBI to task. The committee called for stricter regulation of facial recognition technology at a time when it’s exploding, both in the hands of law enforcement and in business.

The FBI is required, by law, to first publish a privacy impact assessment before it uses facial recognition technology (FRT). For years, it did no such thing, as became clear when the FBI’s Kimberly Del Greco – deputy assistant director of the bureau’s Criminal Justice Information Services Division – was on the hot seat, being grilled by the committee.

The FBI should have published the privacy impact assessment before it launched its advanced biometric database, Next Generation Identification (NGI), in 2010. That database augmented the FBI’s old fingerprint database with further capabilities, including facial recognition. Yet in spite of legal requirements, the public wasn’t informed about the database until 2015 – five years after its launch.

Instead of conducting and making public a privacy assessment, the FBI has plunged ahead with FRT, in spite of what the committee noted are “accuracy deficiencies”. In other words, FRT screws up and misidentifies people.

Studies have found that black faces are disproportionately targeted by facial recognition. According to a study from Georgetown University’s Center for Privacy and Technology, in certain states, black Americans are arrested up to three times their representation in the population, thus meaning they’re overrepresented in face databases. And just as African Americans are overrepresented, so too is their misidentification multiplied. Adding to this all is that facial FRT algorithms have been found to be less accurate at identifying black faces.

During the committee hearing, it emerged that 80% of the people in the database don’t have any sort of arrest record. Yet the system’s recognition algorithm inaccurately identifies them during criminal searches 15% of the time, with black women most often being misidentified.

During last week’s committee hearing, Elijah Cummings, a congressman for Maryland, called for the FBI to test its technology for racial bias, rejecting FBI claims that its system is “race-blind”:

If you are black, you are more likely to be subjected to this technology, and the technology is more likely to be wrong.

[The FBI’s response] is very troubling. Rather than conducting testing that would show whether or not these concerns have merit, the FBI chooses to ignore growing evidence that the technology has a disproportionate impact on African Americans.

The committee noted that human verification is often insufficient as a backup and can allow for racial bias.

The hearing came after recent revelations about the huge collection of images that the government has amassed. In August, a Government Accountability Office (GAO) report revealed that the FBI’s massive face recognition database has 30m likenesses.

Add in the repositories it can access with ease, including that of passport and drivers’ license photos – no warrants required – and in total, at the time of the GAO’s report, the FBI’s Face Services unit had access to nearly 412m images, most of which are of US people and foreigners who have committed no crime, according to the Electronic Frontier Foundation.

Alvaro Bedoya, executive director of the center on privacy and technology at Georgetown Law, last week told the committee that FRT is sorely lacking in oversight:

No federal law controls this technology, no court decision limits it. This technology is not under control.

A significant difference between the FBI’s NGI system and the existing fingerprint database it supplemented is that whereas fingerprints are collected only after a crime has been committed and a suspect has been arrested, the NGI has been proactively populated with images before any crimes have taken place.

The committee chair, Jason Chaffetz, in questioning Del Greco, asked why the FBI didn’t just collect fingerprints or DNA like it collects face images:

Why not get them all in advance? What if we had all 330m Americans’ fingerprints in advance? That would be easier, wouldn’t it?

Why not collect everybody’s DNA? How about when everybody’s born in the US, we take a little vial, a sample of blood? We’d have everybody’s DNA. And then when there’s a crime, then we could go back and say ‘Oh, well, let’s collect that DNA, and now we have 330m Americans. That would be easier, wouldn’t it?

Del Greco’s response:

We collect fingerprints with criminal law enforcement purpose. Only.

Well, exactly, Chaffetz said. What’s scary is how the FBI, and the Department of Justice, proactively try to collect everybody’s face, outside of criminal law enforcement.

And then having a system, with a network of cameras, where you go out in public, that too can be collected. And then used in the wrong hands, nefarious hands… it does scare me. Are you aware of any other country that does this? Anybody on this panel? Anybody else doing this?

His question was met by silence.

We’ve come to learn that besides the known databases – including repositories of passport photos and drivers license photos – some facial recognition databases are “top secret”. That was revealed recently in court documents relating to the case of Charles Hollin, an alleged child molester. Thanks to facial recognition, in January, Hollin was caught, after spending 18 years as a fugitive. It was Hollin’s passport photo, stored in the State Department’s passport photo databases, that led to his seizure.

Catching suspected child predators is a positive for facial recognition, but the debate about the increasingly widespread use of this new technology rumbles on – in particular, about the absence of rules that would protect privacy.

In June, the Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC) joined a coalition of 45 organizations to urge Congress to hold a hearing on the FBI’s biometric database and the risks of facial recognition, including false positives and the risk of law enforcement misusing the technology.

Case in point: in November 2012, a former police officer was awarded just over $1m after she filed suits charging privacy invasion against fellow officers who illegally accessed her driver’s license photo and address more than 500 times.

That happened in Minnesota, by the way: one of the states where it’s now illegal to search driver’s license image databases.

Beyond increasingly vast facial recognition databases, local police have also developed a taste for their own, private DNA databases: as in, databases that are beyond the reach of federal and state laws.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) announced last month that it’s suing San Diego over what it says is the police department’s unlawful policy allowing them to collect DNA samples from minors without first getting parental consent.

With regards to the FBI’s face database and its access to other face image repositories, there’s been no indication that the bureau has any intention to comply with recommendations that the GAO delivered with its August report.

Nor is it clear that the House committee’s admonishments will cause the bureau to switch up how it’s handling facial recognition, nor that it plans to assess how often the technology misidentifies innocent people.