A decade ago, spats between vendors and researchers over the disclosure of security vulnerabilities were typical daily occurrences. Tension has eased in recent years with the growing popularity of bug bounty programs.

Microsoft, for example, once issued frequent complaints about researchers irresponsibly releasing flaw details. Now the company is among those who pay hackers to take their best shot.

But as the recent case of St Jude Medical and MedSec demonstrates, disagreement remains over how best to report vulnerabilities.

To make sense of where things stand, we reached out to MedSec CEO Justine Bone, whose company disclosed security holes in St Jude Medical pacemakers, and Nick Selby, CEO of the Secure Ideas Response Team and a member of the Bishop Fox group tasked with verifying claims about the pacemakers.

Selby recently co-authored an article on the subject with Katie Moussouris, Luta Security CEO and a driving force behind Microsoft’s bug bounty program.

St Jude vs MedSec

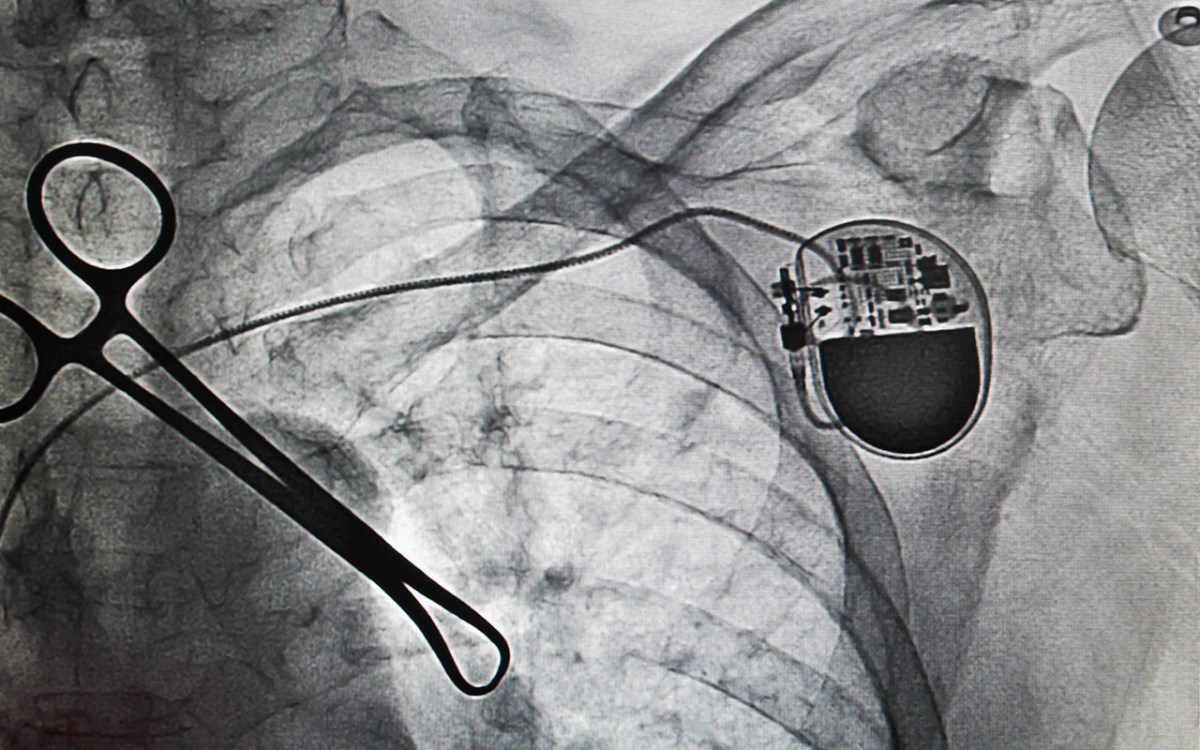

The St Jude case was back in the spotlight earlier this month when the company released security updates for its Merlin remote monitoring system, which is used with implantable pacemakers and defibrillator devices.

The move came five months after the FDA and DHS launched probes into claims that its pacemakers and cardiac monitoring technology were vulnerable to potentially life-threatening hacks.

Naked Security writer Lisa Vaas wrote about the fixes earlier this month:

The pacemaker company said it’s unaware of any security incidents related to, nor any attacks explicitly targeting, its devices. Granted, “all medical devices using remote monitoring are exposed to the risk of a potential cyber security attack,” it said. It was a begrudging acknowledgement, making mention of “the increased public attention on highly unlikely medical device cyber risks”. The tone was hardly surprising, given that the company sued IoT security firm MedSec for defamation after it published what St Jude said was bogus information about bugs in its equipment.

Flaws in communications, hardware and encryption

In a piece for the Dallas Morning News, Moussouris and Selby explained how Bishop Fox was able to verify MedSec’s findings:

Bishop Fox’s team of industry-recognized, independent cybersecurity experts found flaws in communications, hardware and encryption. Most important, the researchers found the systems lacked basic protections against reverse engineering and exploitation. They gained access with “relative ease and little requirement for sophisticated techniques” to the machine SJM claimed was secure. The public summary describes a level of seriously flawed security that neither of us has seen before. That’s shocking, because common sense tells us that medical devices demand especially high security.

An ethics disagreement

There’s no question that vendors and researchers have a better relationship and coordination system in place than what existed in the early 2000s. But this case shows there are still tensions along the way.

Indeed, St Jude wasn’t the only one to react angrily when MedSec and Muddy Waters made their disclosure. Josh Corman, director of the Atlantic Council’s Cyber Statecraft Initiative and founding member of I Am The Cavalry, was among those critical of MedSec’s handling of the matter.

“This will make it harder,” Corman told Dark Reading in September. He said device manufacturers, government agencies and cybersecurity researchers working together have made progress, but that “adversarial actions” like MedSec’s against St Jude will work against that progress.

“If you hurt relationships, you’re going to continue to have unsafe medical devices,” he said at the time.

MedSec had no choice

Though there may have been better ways to handle the disclosure, Selby said MedSec really had no alternative but to disclose what it saw. “Justine [Bone] felt that St Jude had ignored previous attempts to coordinate on the disclosures and fixes,” he said. “She didn’t lie.”

In an email exchange Friday, Bone said MedSec and partner Muddy Waters had one priority in mind when it disclosed the findings – patient safety.

“In partnering with Muddy Waters, our goals at MedSec were to allow patients to understand risks WITHOUT publicly disclosing details of the underlying vulnerabilities, and at the same time compel St Jude to act on the underlying security vulnerabilities,” Bone said. “We were disappointed that St Jude reacted with a lawsuit, but it’s good to see them finally acting on the issues.”

To drive home the seriousness of the flaws, Selby said:

To characterize the kind of poor security decisions in the ecosystem we examined, consider that, to protect your cat photos, Facebook uses encryption that is literally sixteen-trillion-trillion times stronger than that chosen by St Jude Medical used to protect communication between the Merlin@Home box and the implantable devices. STJ used 24-Bit RSA for their communications, AND they left open a 3-Byte back door.

Now what?

Given the conflicts laid bare by this case, the question now is how best to proceed going forward.

To Selby, this was the free market working as it should. It’s rare to find a set of vulnerabilities of this magnitude, and the bugs were very critical. In his opinion, the approach Bone took is a good lesson for vendors not to ignore safety problems in their products.

He said:

Is there a middle ground? It sounds crazy but I think Justine pushed us to the middle ground. The lesson here is that the researcher must be sure they are 100% accurate, and vendors must think twice before blowing off another researcher. It forces us to look at the technology and put technology and math in the driver’s seat. With both sides properly incentivized, this makes for a better responsible disclosure process going forward.

Bone said:

We as an industry work hard to tackle so many diverse problems, and once we make progress – which we have done with the evolution of bug bounty programs and other policy work — we have a tendency to take a problem-solved perspective and try to move on. However, vulnerability management is a nuanced challenge and a one-size-fits-all policy around vulnerability disclosure won’t always be effective. Disclosure is of course one part of the big picture around vulnerability management.

As messy as this particular process was, Selby thinks it’ll ultimately be for the good. “Overall, this was a positive exercise,” he said.

Jim

It truly is a vexing question. But, I think there should be a middle step for researchers who are ignored by vendors, especially when lives are on the line or deep damage is possible:

Release the information that there is a bug, but do not release the details. Then give the vendor a time limit. If action is not taken* by then, the details will be released.

* By “action is not taken”, I mean steps towards resolution, not complete resolution. If the vendor STARTS fixing the problem, then as long as work is occurring towards the end goal, the researchers should hold back their information. Only when the vendor refuses to acknowledge and begin repairs should the researcher move forward with disclosure.

In this case, if SJM had said, “OK, you have a point”, and then started patching things, the researchers should hold off. But, after their first reply, MedSec should have released info that there are flaws, but not what flaws or how to exploit them. At that point, MedSec should start the clock ticking.

NOTE: I’m not sure how long the “clock” should tick on this. But, since MedSec would be looking for movement, not solution, I would think short would be best. Days or weeks at the most.

TonyG

Can’t say I am surprised. When I accidentally discovered how to lock every user out of a well known UK bank, I tried for months to talk to the bank and they basically told me to go away. After 12 months, I told the regulator and only then did the bank contact me, admit they had a problem and were working on a solution. It was no better when they changed another service and I realised I could potentially access other people’s information (not use their account).

What is sad is that when you try to be responsible, tell them privately they have a problem, their only reaction is to tell you to go away.

Mankind has generally learned from mistakes – that is why we have laws and especially consumer protection laws. Sooner or later we may well have to legislate on how to act responsibly on this.