If you’ve ever used your credit card online, or over the phone, you’ve probably been asked for something known informally as the “short code” or “security code”.

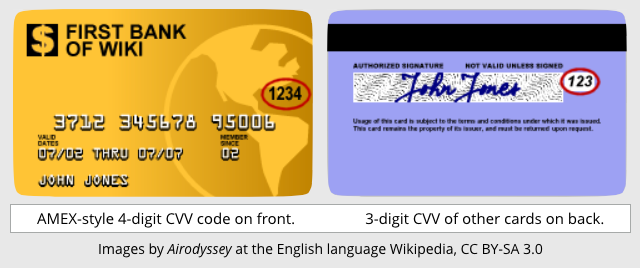

That’s usually a three-digit number physically printed (but not embossed) at the right hand end of the signature strip on the back of your card.

Three digits don’t sound enough to make much of a password, and in normal circumstances they wouldn’t be.

But for what are known as card-not-present transctions, the CVV, or Card Verification Value as it is commonly known, provides a handy degree of protection against one of the most common sorts of credit card fraud, namely skimming.

Skimming is where the crooks use a booby-trapped card reader, for example glued over the real card reader on an ATM, or cunningly squeezed into the card slot on a payment terminal, to read and record the magnetic stripe on your card.

Even if you have a Chip and PIN card, the magstripe contains almost enough information for a crook to convince a website they have your card.

For example, your name as it appears on the front of the card, the “long code”, usually 16 digits across the face of the card, and the expiry date are all there on the magstripe, ready to be copied surreptitiously and used on the web.

The CVV therefore acts as a very low-tech barrier to card-not-present fraud, because most websites also require you to type in the CVV, which is not stored on the magstripe and therefore can’t be skimmed.

Of course, there are numerous caveats here, including:

- The vendor mustn’t store your CVV after the transaction is complete. The security usefulness of the CVV depends on it never lying around where it could subsequently fall foul of cyberthieves.

- The payment processor mustn’t allow too many guesses at your CVV. With unlimited guesses and a three-digit code, even a crook working entirely by hand could try all the possibilities with a few hours.

Guessing CVVs

Researchers at Newcastle University in the UK recently decided to see just how effectively the second caveat was enforced, by trying to guess CVVs.

The initial findings were encouraging: after a few guesses on the same website, they’d end up locked out and unable to go and further.

Then they tried what’s called a distributed attack, using a program to submit payment requests automatically to lots of websites at the same time.

You can see where this is going.

If each website gives you five guesses, then with 200 simultaneous guesses on a range of different websites, you can get through 1000 guesses (200 × 5) in quick order without triggering a block on any of the sites.

And with 1000 guesses, you can cover all CCV possibilities from 000 to 999, stopping when you succeed.

Then you can go to a 201st site and order just about whatever you like, because you’ve “solved” the CVV without ever actually seeing the victim’s card.

In other words, you’d expect the payment processor’s back-end servers to keep track not just of the number of CVV guesses from each site, but the total number of guesses since your last successful purchase from any site.

According to Newcastle University, Mastercard stopped this sort of distributed guessing, but Visa did not.

Should you worry?

Considering how much credit card fraud happens without any need for CVV-guessing tricks like this, we don’t think this is a signal to give up online purchases entirely this festive season.

Afte all, if any of the sites or services you used recently kept your CVV, even if only to write it down temporarily while processing your transaction, you’re exposed anyway, so CVVs aren’t a significant barrier to determined crooks.

And if you’ve ever put your card details into a hacked or fraudulent website – even (or perhaps especially) if the transaction was never finalised – then the crooks probably already have everything they need to clone your card.

What to do?

A few simple precautions will help, regardless of your card provider:

- Don’t let your card out of your sight. Crooks working out of sight, even for just a few seconds, can skim your card easily simply by running it through two readers – a real one to process the transaction you’re expecting, and a handheld skimmer to copy your card’s data. They can also snap a sneaky picture of the back of the card to record both your signature and the CVV.

- Try to use the Chip and PIN slot when paying in person. Most chip readers only require you to insert your card far enough to connect up to the chip. This leaves most of the magstripe sticking out, making skimming the card details harder.

- If in doubt, find another retailer or ATM. Most ATMs still require you to insert your whole card, and can therefore be fitted with glued-on magstripe skimmers. If you aren’t sure, why not get hold and give it a wiggle? Skimmers often don’t feel right, because they aren’t part of the original ATM.

- Stick to online retailers you trust. Check the address bar of the payment page, make sure you’re on an encrypted (HTTPS) site, and if you see any web certificate warnings, bail out immediately.

- Keep an eye on your statements. If your bank has a service to send you a message notifying you when transactions take place, consider turning it on.

DG

A number of big banks also offer the facility of creating ‘virtual credit cards’ with a set limit and short expiration durations. Consumers should make use of such facilities when the vendor/merchant isn’t a top-tier retailer like Amazon.

MrBlz

Excellent suggestion. I use this at Citi quite often. Another good idea is to set alerts for charges. I set all my cards to alert me for charges over $20. I don’t care about getting extra texts.

Matt Parkes

Correct me if I am wrong but Amazon dont ask for CVV, I am an Amazon account holder and while Amazon store my 16 digit PAN (display the last 4 digits when I am logged in) and supposedly my expiry date and card type, they never asked for the CVV and I use the site regularly. I watched a retail watchdog type TV program recently talking about card security and they stated that Amazon do not ask for this as it helps them reduce risk of non-compliance to PCI DSS and due to their size the transaction cost placed upon them by their payment processor or acquirer due to the increase risk of fraud from not asking for the CVV was not enough to make them do otherwise. Is this true and if so this would make me extremely worried about using them in future, irrespective of the fact that they would refund me any loss if the worst happened.

Paul Ducklin

Well, they aren’t allowed to store your CVV, so they either have to ask for it every time or find another way. If the only way you can trigger a purchase using your stored details is via some other sort of authenticated login, I suppose that is considered at least as safe as asking for the CVV. If you are using two-factor authentication (2FA) and you need to use a 2FA code every time you authorise Amazon to charge something to your card, I’d say you’re OK. It’s sites where a one-time purchase can be made simply by typing in details from your card that the CVV provides a little bit of extra protection against arrant misuse.

Matt Parkes

I only enter a user name and password on Amazon, no 2FA and they only have my PAN, expiry date and card type along with name and address. There is no request for a security code whatsoever not even when i first signed up and not on return orders. Apparently they are happy to pay higher transaction costs and higher liability insurance and happy to refund me should I report fraudulent activity and it is verified. Which OK fair enough but I think I would much prefer them to be pro active than reactive when it comes to card security.

jkindall

Amazon asks for the CVV the first time you use a card you’ve added. After that transaction goes through, they don’t ask for the CVV again unless you add a new shipping address.

Derek

No Amazon NEVER requires a CVV code for transactions

Jeff

DG — Well said. I do this all the time for every on-line transaction and have for years. In addition to being able to set limits and expiration dates, my Bank of America card also ties the virtual card number to the vendor when it’s first used, so one can have a number good for a vendor for a full year (their max expiration time), and the number can’t be used elsewhere if BoA’s system is hacked.

Strangely, Discover Card was an early adopter of virtual numbers, but dropped it a couple of years ago. When I’ve asked them about this, they reassure me that they have zero fraud liability protection. But just because I have zero liability doesn’t mean that any fraud is of no cost to me — we all end paying for fraud via higher prices. I had been using Discover for virtual numbers for years, but now do all my on-line transactions with my Bank of America virtual numbers.

Jamie

The biggest online retailer doesn’t even ask for CVVs.

Anonymous

It’s because it has such an advance system that detects if the transaction is legit or not, with a 99% success rate.

Kabir

Here in India, the law requires an OTP to be sent to your mobile phone which you then have to enter on the payment page to complete the transaction, apart from the CVV.

Brad

Wonder what they are going to do once NIST ratifies that this isn’t an acceptable way of securing the transaction?

Jim Darling

Is there a law in India that everyone HAS to own a mobile phone?

Paul Ducklin

Many, if not most, developing countries have mobile phone penetration “above 100%”. OK, lots of people don’t have one and the numbers are made up by people who have two, but try travelling to African cities and see how much society and the economy depends on prepaid mobile phones. (And marvel at how ubiquitous the coverage is – if you wait more than one second for an SMS to arrive then the network is broken :-)

You don’t need a contract, and as long as you use your SIM once every now and then you will keep your number alive.

It’s not rich people in rich countries who have bankrolled the mobile phone industry in the past couple of decades – those people weren’t early adopters because they already had contracts and landlines.

Jim Darling

“Don’t let your card out of your sight. ”

~

How do you do this at a restaurant? The server always takes your card and goes off to wherever they process the transaction. Are we suppose to follow them?

Paul Ducklin

I don’t hand my card to the waiter. I go with them to the pay point. Or I draw enough cash in advance.

Outside the US, of course, things are different these days. Wherever I’ve lived in the past few years the waiter brings the payment device to you and you insert the card yourself into a slot that isn’t deep enough to read the magstripe, only to access the chip. Of course, this still isn’t perfect because a tampered device could be rigged to phish your PIN, but the fact that you have to enter the PIN makes it pointless to hand over your card – it’s no use unless you are there too.

So no one even asks for you to give them your card any more. You go to the payment device or the device comes to you.

Dave

I’m about to go travelling in India so I scraped the CVV number off the back. Both me and my family know what the number is. Is this OK?

Paul Ducklin

I do that. In theory it could cause an alert merchant to get suspicious (technically, it means the card’s been tampered with) but I’ve never been refused service because of it.

Back in the days when merchants were supposed to check your signature by turning the card over, [a] few ever even looked and [b] I never got my card turned down, even when the signature strip had worn away in my wallet leaving the words VOIDVOIDVOID right across the card.

In short: I dont think you’re supposed to scratch off the CVV, but I can’t see how it would make you less secure to do so. I wouldn’t go public about how you’ve told your whole family to remember it, though. That might be considered a violation of T&Cs, or something, so there is no point in having that detail on the record. (Speaking of the record, I am not suggesting to lie about thge issue, just that I wouldn’t volunteer the info :-)

Christopher Sourp

I have just had my debit card info stolen. Two attempts at fraudulent use was caught. I am not out any money yet. I am trying to find out if there are still online retailers that DO NOT require that you enter the CVV when making a purchase. This would help me greatly to find out if my card was skimmed or physically compromised. The consumer is given ZERO info when there card has been compromised and that is upsetting.