A Naked Security reader just drew our attention to a recently released extension in the Chrome Web Store called AccessURL that is being talked about positively on mailing lists and online lifestyle websites.

AccessURL offers to share access to your online accounts temporarily without giving away your password, so it sounds like just the ticket if you occasionally want to let colleagues tweet on your behalf, or to let a friend use your video streaming service while you’re off-grid for a few days.

Our reader wanted to know, “Is this a good idea, or in fact a really bad one?”

Our answer is simple: it’s a bad idea.

AccessURL works by copying and sharing your session cookies, and here’s why you shouldn’t do that.

Cookies explained

Web servers deal with keeping track of who and where you are using cookies, a standard way of remembering settings and configuration data while you move around on on a website.

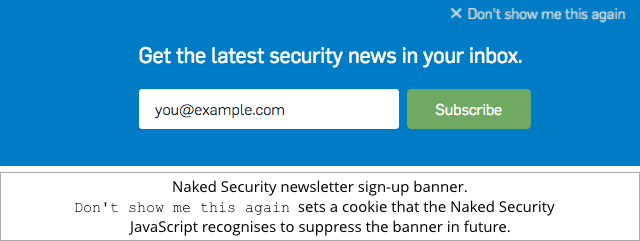

For example, Naked Security articles include a banner that looks like this, asking you if you would like to subscribe to our daily email newsletter:

If you don’t want to subscribe, and you don’t want to be asked again, you can just click on Don't show me this again, which sets a cookie that our site’s JavaScript will look out for and use to suppress the banner in future. (If you’ve ever wondered why clearing your cookies makes the banner reappear, now you know why.)

The banner vanishes because we set a cookie called nakedsecurity-hide-newsletter to have the value true.

(By “having the value true”, we mean quite literally that the cookie consists of the ASCII characters t, r, u and e to make up the word true as a string of text – the signal that you don’t want to see the banner.)

In technical jargon, cookies provide a way of maintaining state between one web request and another.

Session cookies

Without cookies, you wouldn’t be able to login to a website at all, because there would be no way of remembering your identity from one page to the next, so you’d need to put in your username and password over and over again.

So, logging in is usually handled with what’s called a session cookie or session token, a bit like our hide-newsletter cookie, but holding a unique (and time-limited) cryptographic secret that your browser includes in future requests to the same website, so the server knows it’s you returning for more.

If someone steals your session cookie, they can maliciously add it into their own web requests; in many cases, that’s enough to masquerade as you.

That’s known as a session hijack, and it means that they end up authenticated in your name, but without ever needing to know your username and password.

In fact, just over six years ago, a free hacking tool called Firesheep appeared that automated the process of session hijacking.

In those days, many sites encrypted your password, but didn’t encrypt the session after that, thus transmitting your session cookies in plain text where they could easily be eavesdropped by network sniffing tools such as Firesheep.

Firesheep got its name from the fact that it ran as a Firefox extension, and because it added you to what hacker conventions call the wall of sheep – a list of users whose authentication data has been spotted on the network unencrypted and then displayed for everyone to jeer at.

One good side effect of Firesheep is that it proved to us all that web encryption (where you use URLs beginning with https instead of just http) is important all the time, not just for the part of the session where you actually supply your password.

Indeed, in the next few years after Firesheep, all major web properties switched over to using HTTPS all the time, thus making session hijacking much harder.

These days, the easiest way to steal someone’s session cookies when they are using HTTPS is to grab their traffic before it’s encrypted or after it’s decrypted, for example by sneaking malware into the browser or onto the server.

A malicious browser plug-in, for instance, can inspect web content before it gets HTTPSified, extracting private data such the selfsame session tokens that Firesheep stole in the days before your whole session was encrypted.

Stealing session tokens instead of passwords can actually make things easier for the crooks: a session token denotes an already logged-in connection, which neatly sidesteps any two-factor authentication (2FA) that might be turned on.

Firesheep by consent

You’ve probably guessed where this is going.

AccessURL works by installing a Chrome extension that basically performs what you might call “Firesheep by consent”.

It extracts session cookies for web logins you select and shares them via the cloud with chosen friends.

The idea is that you can quickly and easily expire any session cookie you’ve already shared simply by logging out on your computer, causing the server to consider the old cookie invalid.

If you’ve shared your password with other people, the only way to “unshare” it and lock them out is to change it, assuming one of those other people hasn’t changed it already, thus locking you out instead.

So, it’s easy to say to yourself, “This cookie sharing system is better than sharing my actual password, so I’ll take the risk, even though I’m giving someone else open slather on my account, at least for a while.”

We strongly urge you not to do this.

Even if the AccessURL servers handle the cryptographic details so that the service can’t decrypt the session tokens itself (which would amplify the risk even further), it’s cloning an already-authenticated session, bypassing any 2FA and putting you at much the same short-term risk as if you handed over your account entirely.

There are typically a few things you can’t do with a session cookie alone: most online services, for example, make you enter your password again if you try to change your profile information, including updating your recovery email address or resetting your password.

But if a cloned session cookie works at all, it will probably work for most parts of your account…

…so if your friends turn out to be infected with cookie-stealing malware themselves, or occasionally leave their computers unlocked for a moment, they’re putting your online identity at direct risk, too, even though they don’t know your password.

In short: sharing session cookies sounds better than sharing passwords, but you need to treat them as two side of the same coin.

We recommend: don’t share passwords, and don’t share session cookies either.