A security researcher who goes by @avicoder just revealed a security bungle made earlier this year by Vine.

In case you missed it, Vine is to YouTube what Twitter is to blogging: your videos are limited to just six seconds, to encourage you to upload early, upload often.

At any rate, that must have been how Twitter saw it, because it acquired Vine back in 2012, the same year that Vine was founded.

In this story, Avicoder didn’t really hack Vine, for example by finding programming bugs or other vulnerabilities in the service.

But the outcome was as good as a traditional hack – or, perhaps, even better. [Surely you mean worse? – Ed.]

Simply put, Avicoder combined openly available search tools with what’s often called “lateral thinking” in order to uncover a security blunder that meant he didn’t need to do any traditional hacking.

The story is an important reminder that just because a server isn’t announced, isn’t purposefully indexed by search engines, and isn’t linked to from anywhere…

…doesn’t mean it can’t be found.

For example, if you have example.com, most of us would assume you probably also have www.example.com, or mail.example.com, or ns1.example.com (web, mail and name servers respectively).

We might guess at backup.example.com, login.example.com, and similar names; and we’d probably expect them to be online on purpose, and carefully protected as as result.

But if we found unexpected servers such as internal.example.com, codingdatabase.example.com, or pre-release.test2.example.com, we’d definitely want to take a closer look, in case we’d stumbled across a server that wasn’t carefully protected because it wasn’t supposed to be “on the outside” at all.

A sniff of the target

That’s pretty much what Avicoder did, though the process wasn’t quite as simple as finding an intriguing server and logging in.

All that he needed to get going, however, was a sniff of the target, which is exactly what he got when he started looking at what docker.vineapp.com was all about.

Docker is an online toolkit that helps you maintain a set of working environments for software development, such as copies of the source code for each platform you support, plus one or more virtual machines (software computers) to build, try and test the product on each platform.

You can put Docker repositories on the open internet, assuming you secure them somehow, for example using passwords and two-factor authentication.

But that wasn’t what Avicoder found.

He didn’t know how to get into Vine’s Docker databases, but he knew he probably could if he kept trying, thanks to the giant hint when provoked the reponse /* private docker registry */ without needing to log in.

Indeed, after a bit of trial and error and a few false starts:

I was able to see the entire source code of Vine, its API keys and third party keys and secrets.

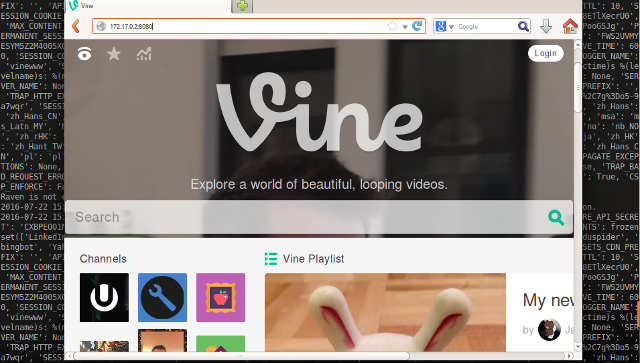

He even found a Vine virtual machine image that he could start right up and use to run his very own local clone of Vine:

(Click to see this image in the original posting.)

Just imagine how handy that would be to a phishing gang: no need to create home-made mockups of Vine’s service with fake login screens when you can run a pre-prepared visual clone that looks and feels like the real deal.

Avicoder told Twitter; Twitter took the errant server offline within minutes; and Avicoder received a bug bounty of $10080.

As far as we know, no one’s Vine account or data was attacked or compromised using this hole, so everyone benefitted.

What to do?

- Never put resources online and rely on them staying unnoticed because they are “unadvertised”. Assume that someone will find them.

- Always enable authentication to access your services, even internally. Assume that someone will find them.

- Respond quickly if someone reports servers that shouldn’t be there. Assume that someone else will find them.