Thanks to Gábor Szappanos of SophosLabs for the research behind this article.

Ransomware gets a lot of attention these days, and understandably so.

It’s the digital equivalent of a punch in the face: there’s no doubt what’s happened, and the crooks leave no stone unturned to make sure you know it.

Some ransomware not only creates some sort of HOW-TO-PAY document in every directory where there are scrambled files, but also changes your desktop wallpaper so that the payment instructions are visible all the time.

You can argue, however, that less visible malware attacks are even worse, especially if you only find out about them days or weeks after they started, and they include some sort of data-stealing payload.

Like the range of malware that SophosLabs researcher Gabor Szappanos (Szapi) was reviewing recently while working on a paper about Word-based attacks.

Szapi was looking at a particular subset of Word-borne hacks: what are known as exploit kits.

Exploit kits are pre-packaged, booby-trapped files that automatically try to take over applications such as Word or Flash as soon as you open up one of the malicious files.

The idea is to bypass any pop-up warnings that would usually appear (such as “you need to enable macros,” or “are you sure you want to install this software”) by crafting the exploit file so it causes a controllable crash in the application that just loaded it.

Szapi noticed that all of the exploit kits he’d covered in his paper (going by names like Microsoft Word Intruder, AK-1, AK-2, DL-1 and DL-2) had been used at some time to distribute data-stealing malware known as KeyBase.

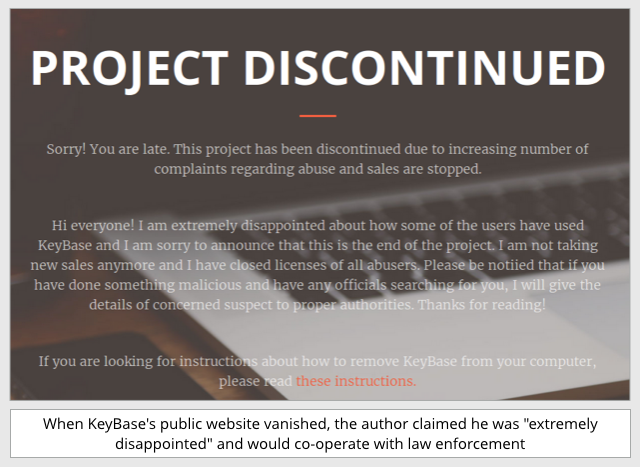

His first thought was along the lines that “KeyBase ought to be dead by now, because it’s been around for a while, it’s well-known, and the author himself took it offline long ago.”

Sadly, however, the KeyBase Trojan is alive and well, even though it’s no longer openly available.

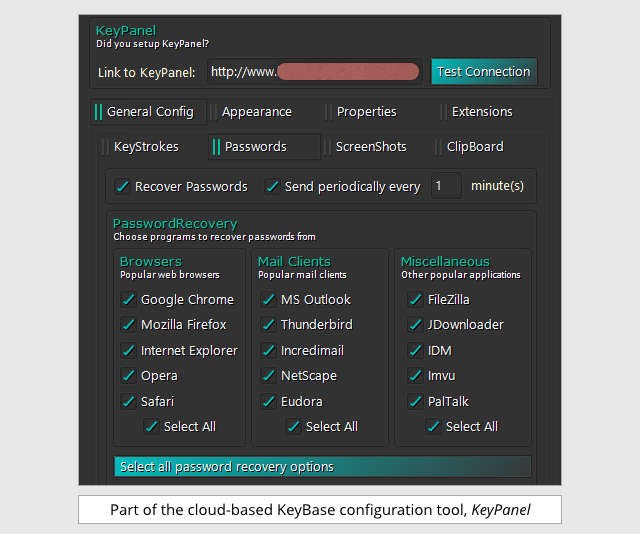

KeyBase is primarily a keylogger, meaning that it keeps track of what you type, collects up the data, and regularly uploads it to the crooks using innocent-looking HTTP requests.

When would-be cybercrooks set it up, there’s a point-and-click configuration system, so they don’t need any technical knowledge to decide what parts of your digital lifestyle to spy on:

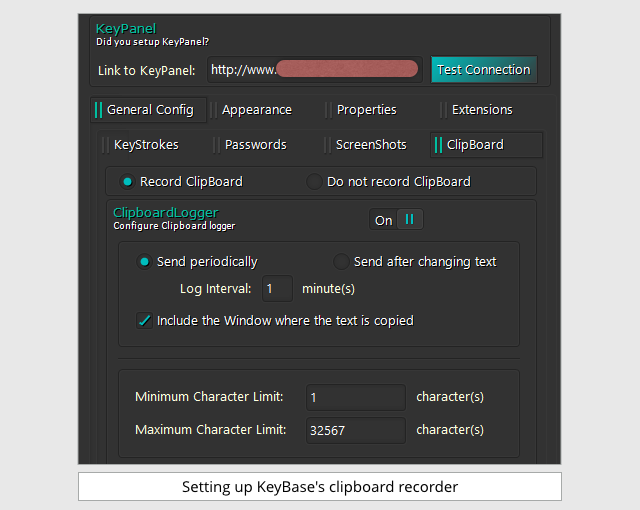

Amongst other things, they can also keep track of what passes through the clipboard:

Monitoring the clipboard gives away plenty of information about your business, because you generally use the clipboard for items of immediate importance, such as copying-and-pasting text out of emails into documents, or vice versa.

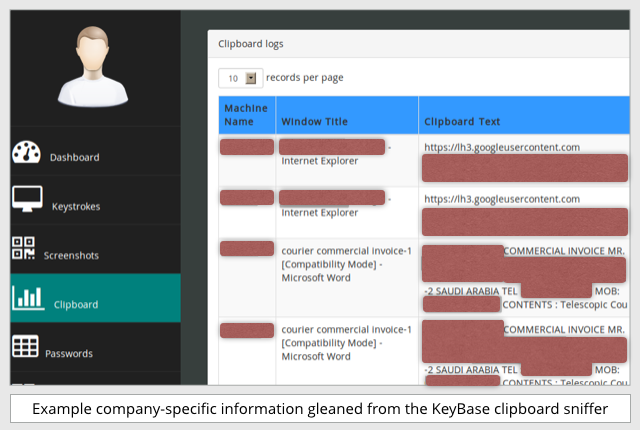

That makes the clipboard a handy signal of interesting data about your business, such as this example data from KeyBase’s cloud-based servers:

KeyBase and other malware families like it are examples of Crimeware-as-a-Service (CaaS).

That’s where a group of technically-savvy criminals provides the servers and the control panels, renting out access to allow any number of non-technical crooks to jump right into the cybercrime scene.

Once a team of crooks has inside information on your business, such as your email passwords and a list of the people you do business with, they are well-placed to start bleeding you for money.

With ransomware, you generally know beyond doubt what has happened; you have a short list of choices of what to do next; and you have a firm price in Bitcoin staring you in the face.

But with system-sniffing malware like KeyBase to teach them how to login to your accounts, crooks can correspond with your creditors and debtors using your email address; change account numbers to divert payments; alter invoices; place bogus orders…

…and then, because they control your logins, they can cover their tracks (for example by deleting sent emails that you’ll know you didn’t write) to keep their swindle going as long as possible.

As we wrote in a recent article about a similar keylogging malware family known as HawkEye:

This is effectively […] high-tech crime available to low-tech criminals.

They [can buy] in the necessary booby-trapped documents; [buy] in the keylogger; [pay] someone to send very small quantities of spam; and then [settle] down to carry out old-fashioned, targeted deception and fraud.

What to do?

- Patch promptly. Word exploit kits such as those mentioned above usually rely on security holes that have already been been patched.

- Keep your security software up-to-date. A good anti-virus can block exploit kits, keyloggers and other malware in numerous different ways.

- Beware of unsolicited attachments. This can be hard if your job is business development and the email is a Request For Quotation, but avoid opening just any old document.

- If your email software supports it, use 2FA. That’s short for two-factor authentication, those one-time codes that come up on your phone or on a special security token. With 2FA, just stealing your email password isn’t enough on its own.

- Have a two-person process for important transactions. Paying invoices and changing account numbers for remittances shouldn’t be too easy. Require separate approval from a supervisor, so you always get a second opinion when company payments are at stake.

LEARN MORE ABOUT 2FA

(Audio player above not working? Download MP3, listen on Soundcloud or access via iTunes.)

Person

“Have a two-person process for important transactions. Paying invoices and changing account numbers for remittances shouldn’t be too easy. Require separate approval from a supervisor, so you always get a second opinion when company payments are at stake.”

Good advice in response to online thievery and offline embezzlement. The more eyes that watch every bill, the better. Can hurt to get more than just a second opinion!

In my last job, every credit card statement was reviewed by at least 6 employees in generally ascending order of rank. I ordered materials that my fellow employees requested. I attached employees’ original written requests and original vendor receipts to correspond with every line item in each statement. After I attached the supporting documents to the statement, the review process went, as follows:

1. My supervisor reviewed the statements and supporting documents, requests, and receipts before she submitted them to her supervisor.

2. My supervisor’s supervisor reviewed the statements and supporting documents before he submitted them to Accounting.

3. The Accounts Payable assistant reviewed the statements and supporting documents before he submitted them to the Assistant Controller.

4. The Assistant Controller reviewed the statements and supporting documents before she submitted them to the Controller.

5. The Controller reviewed the statements and supporting documents before he submitted them to the CFO.

As you can see, there was no chance that I could abuse the company credit card that was in my name and to which I had access – not that I would want to do so, anyway.

My former employer was fairly small yet it had several departments. Each department had at least one employee who had access to a company-issued credit card. The reviews process for those cards’ statements was the same as that above. I think only the CEO and CFO’s statements were subjected to less scrutiny. (This might be OK if the CEO isn’t Jeffrey Skilling.)

My former employer did things right. Their example should be followed by other employers. Employees who handle company money need to be watched by several pairs of eyes.

I weep when I hear stories of employees (at other firms) who handle company issued-credit cards and pay (fake or otherwise) statements with little or no managerial oversight. Can you say “embezzlement”?