Thanks to Mark Loman of SurfRight for his behind-the-scenes work on this article.

SophosLabs and our SurfRight colleagues just alerted us to an intriguing new ransomware sample dubbed RAA.

This one is blocked by Sophos as JS/Ransom-DDL, and even though it’s not widespread, it’s an interesting development in the ransomware scene.

Here’s why.

Ransomware, like any sort of malware, can get into your organisation in many different ways: buried inside email attachments, via poisoned websites, through exploit kits, on infected USB devices and occasionally even as part of a self-spreading network worm.

But email attachments seem to work best for the cybercrooks, with fake invoices and made-up court cases amongst the topics used by the criminals to make you think you’d better open the attachment, just in case.

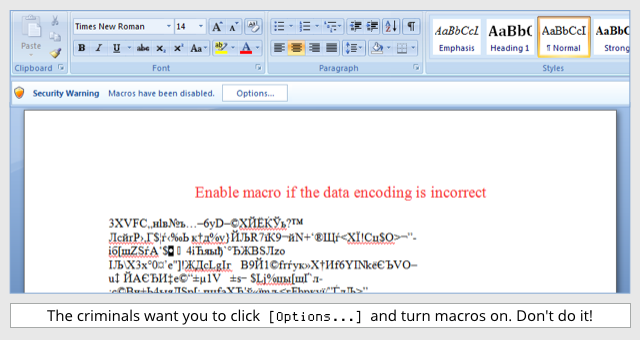

In 2015, most ransomware arrived in Word documents containing what are known as macros: script programs that can be embedded in documents to adapt their content in real time, usually as part of your company’s workflow.

The problem with macros, however, is that they aren’t limited to adapting and modifying just the document that contains them.

Macros can be full-blown programs as powerful as any standalone application, and they can not only read and write files on your C: drive and your local network, but also download and run other files from the internet.

In other words, once you authorise a macro to run, you effectively authorise it to install and launch any other software it likes, including malware, without popping up any further warnings or download dialogs.

You can see why cybercrooks love macros!

Fortunately, macros are turned off by default, so the crooks have to convince you to turn them back on after you open their malicious documents.

Excuses they’ve used include needing to enable macros “for security reasons” (they mean for insecurity, of course), and to change character sets to make documents legible, like this sample that delivered the Locky ransomware:

The switch to JavaScript

By the start of 2016, many crooks were steadily shifting their infection strategy as the world began to realise that enabling macros was a really bad idea.

These days, a lot of ransomware arrives in JavaScript attachments.

In case you’re wondering why anyone would open a .JS file that was pretending to be a document, remember that:

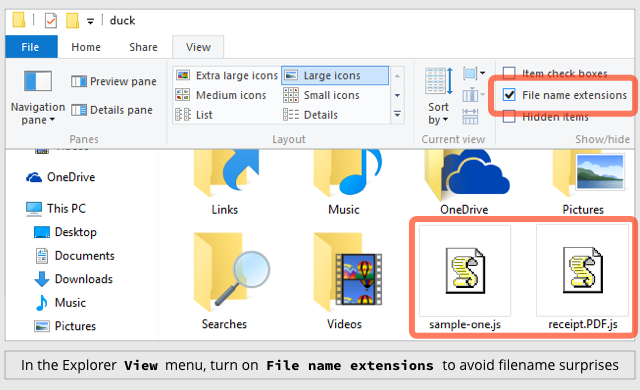

- Windows doesn’t show file extensions by default. So a file called

Invoice.txt.jsshows up as the altogether more believableInvoice.txt. - Windows uses ambiguous imagery to denote .JS files. Scripts appear with an icon looking like a scroll of parchment, making them look like documents instead of programs. (See below.)

Usually, the malicious JavaScript connects to a download server, fetches the actual ransomware in the form of a Windows program (an .EXE file), and launches it to complete the infection.

Pure JavaScript

But JS/Ransom-DDL takes a different approach.

The JavaScript doesn’t download the ransomware, it is the ransomware.

This is possible because:

- JavaScript is a general-purpose programming language. It can be used for anything from modest scripts to full-blown applications.

- On Windows, JavaScript outside your browser runs in the Windows Script Host (WSH). This doesn’t restrict or “sandbox” the script code, so it can do anything a regular application could do.

- The crooks used freely-available cryptographic source code in the malware. This made the implementation much easier, because the hard programming work was already done.

No additional software is downloaded, so once the JS/Ransom-DDL malware file is inside your network, it’s ready to scramble your data and pop up a ransom message all on its own.

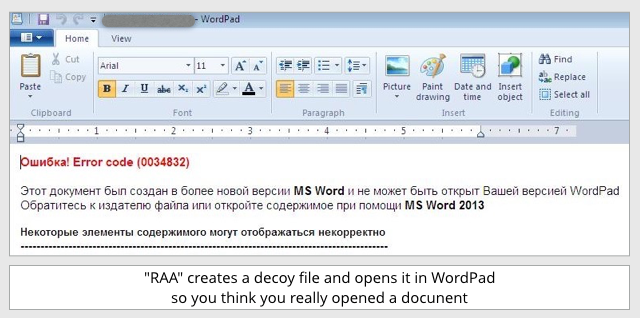

While it’s at work, it opens a file known as a decoy document in WordPad:

Error! Error code (0034832)

This document was created in a newer version of MS Word and cannot be opened with your version of WordPad.

Contact the creator of the file, or open the file with MS Word 2013.

Some parts of this content may not be displayed properly.

The decoy file contains a bogus error message that is supposed to convince you that the file you just opened really was a document, and to distract your attention while the ransomware goes to work.

The payload

Strictly speaking, this ransomware isn’t completely self-contained: like many ransomware families, its first step is to “call home” to a server operated by the crooks to acquire an encryption key.

The server replies with a uniquely-generated identifier and a randomly-created AES encryption key, so that victims can’t share decryption keys with one another.

If your data ends up scrambled, you need to quote your unique identifier and buy back the matching AES key to unscramble your data.

(The AES key downloaded by the malicious JavaScript is only ever kept in memory, so once the encryption is complete and the JavaScript program exits, the crooks have the only remaining copy of the key.)

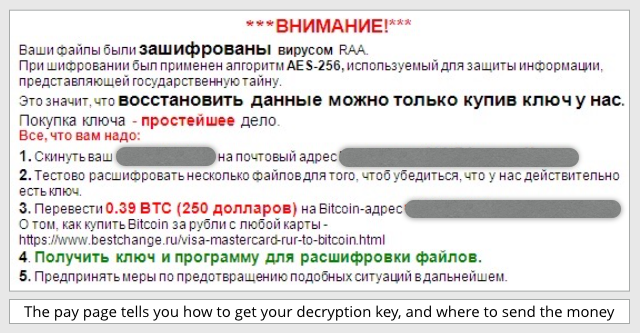

Once the encryption is complete, you’ll see a README page telling you how to buy back the key to recover your data:

The gist of this “pay page” follows the usual ransomware recipe:

***ATTENTION!***

Your files have been encrypted by the RAA malware.

The AES-256 algorithm was used for encryption – the same encryption that is used to protect state secrets.

This means that restoring data is only possible by buying the key from us.

Buying the key is the simplest solution.

You don’t need to understand Russian to figure out that the asking price is 0.39 Bitcoins, or approximately $250.

The crooks also suggest (point 2) that they will decrypt a few files for you first if you need proof that they really have the key, although they don’t say up front exactly how you are supposed to send them the test files.

That’s not all

Most ransomware attacks we’ve seen in the last few years have started by scrambling your files, and finished by unscrambling your files once you’ve paid up.

In other words, the cybercrime component was all about squeezing you to pay the ransom, with the ransomware aspect essentially being the beginning and the end of the crime.

After decrypting your files and making sure that the ransomware program has been removed so it can’t accidentally strike again, the theory is that you’re back where you were before the attack started.

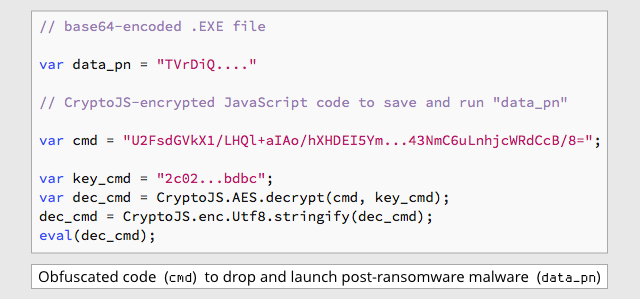

But JS/Ransom-DDL is interestingly different, because it deliberately installs a secondary malware infection: a password stealer blocked by Sophos products as Troj/Fareit-AWR.

This Fareit infection isn’t downloaded; instead it is encoded using base64 into a JavaScript string that is stored inside the ransomware file, and installed as a parting gift by the ransomware.

The program code that drops the Fareit file onto your hard disk and launches it is deliberately obscured by encrypting it with AES, using a decryption key stored inside the malware:

The dropped Fareit malware is saved into your MyDocuments folder using the name st.exe.

What to do?

- Read our article How to stay protected against ransomware.

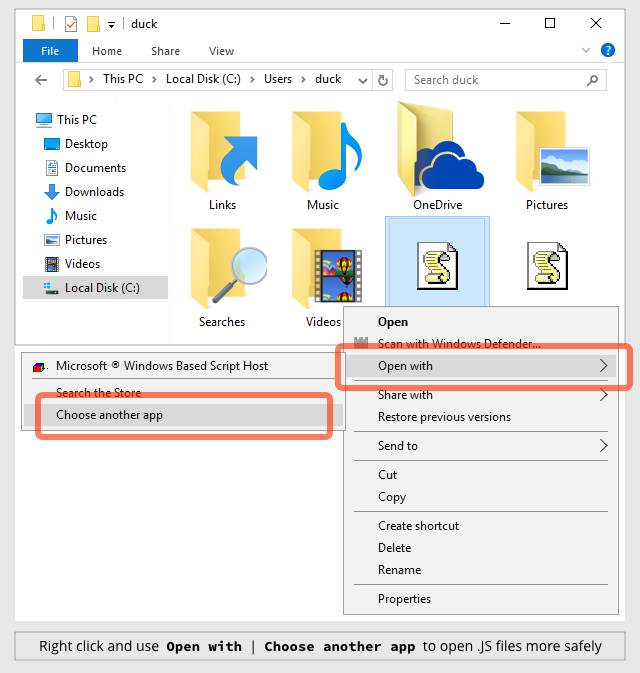

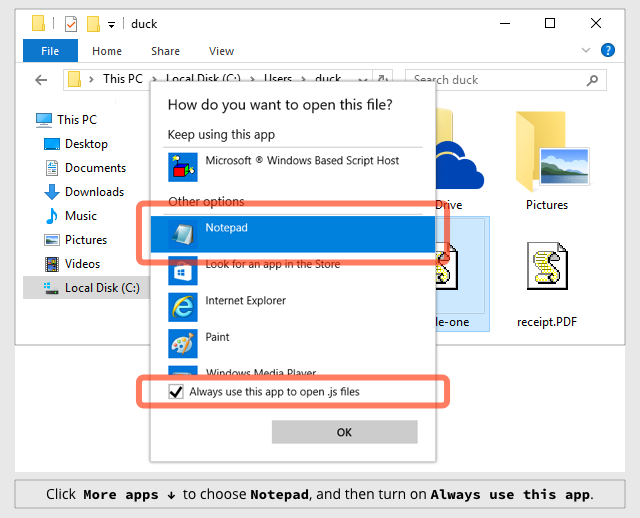

- Configure Windows to show file extensions. This gives you a better chance of spotting files that aren’t what they seem. (See below.)

- Consider configuring Windows to open JavaScript files with NOTEPAD, not with WSH. This displays .JS files harmlessly as text rather than running them as programs. (See below.)

- Consider using a protective recovery tool like Hitman Pro Alert from Sophos. This can detect when malware, including JS/Ransom-DDL, starts scrambling your data, killing the malicious process and rolling back the unauthorised changes so you don’t need to pay up.

By the way, if do you pay up for ransomware, never assume that the “recovery” tool provided by the crooks will clean up your computer as well as unscrambling your data.

As far as we know, the ransomware in this case might itself be intended as a sort of decoy, to distract you from the fact that you’ll still be infected with the password stealing component, even if you recover from the encryption part.

HOW TO TELL EXPLORER TO OPEN .JS FILES WITH NOTEPAD

Right click on a .JS file and then click on: Open with | Choose another app | More apps ↓

Select Notepad and then turn on Always use this app to open .js files:

HOW TO TELL EXPLORER TO SHOW FILE EXTENSIONS

Click on the View menu and turn on the tick-box labelled File name extensions:

Aaron Higgins

Insidious is what that is. Thanks to bringing this new threat vector to our attention.

Bryan

Wow. Yikes. Thanks Paul.

Wish it were feasible for HTML6 to supplant JavaScript as HTML5 similarly obsoletes** Flash players… Who knows? With brighter minds than mine on it maybe it can happen.

On the lighter side (sorta) the text at a certain micro site that one might cathartically enter into one’s browser after reading this article (or while completing a form rife with JS) is far more family friendly–and even somewhat constructive–than it once was.

** is this a transitive verb? Is now.

James Edward Lewis II

“Obsolete” has been used as a transitive verb in computing for as long as I can remember, but it turns out that the first verb with a similar meaning was “obsolesce” (intransitive, meaning “become obsolete” or “be obsoleted”); the transitive verb “obsolete” now appears to be an Americanism (I’ve only seen it in American general-purpose dictionaries so far, but I have seen it in every dictionary I checked, and Oxford Dictionaries Online says “Chiefly American”), but the Oxford English Dictionary attests it as far back as 1640, less than a century after its earliest attestation for the adjective (when, as might be imagined, English was mostly confined to Britain).

Also, much of what allowed HTML5 to supplant Flash was a new set of DOM APIs and other hooks into JavaScript (that is, JS became *more* important as plugins faded away); it looks like scripting is here to stay on the Web, and anyway, this vulnerability is based on JS as a desktop scripting language, which itself likely can’t be supplanted by an alternative that is safe from similar exploits (consider, for example, batch files and PowerShell scripts).

Bryan

Thanks for the references; the usage sounded odd to me but felt right, so I footnoted (har) a disclaimer. Duck, do Brits and Aussies prefer “renders obsolete” instead?

JavaScript: I was hoping to be wrong yet fearing I’m correct in assuming it’s here to stay–I didn’t know the nuts & bolts of HTML5’s hooking further into JS. Maybe HTML8 will find a less-vulnerable implementation that still allows nifty web-paging**

** did I do it again?

:-)

Cheers, James. Thanks again!

Paul Ducklin

The use of “obsolete” as a verb rather than as an adjective is listed by my British and American dictionaries as “chiefly US,” but I think you can consider it mainstream on both sides of the Atlantic (North or South).

I think the real problem is that in IT, it’s very often used wishfully, whether as an adjective or a verb. For example, we might say “HTML5 has made Flash obsolete in your browser,” when what we mean is “if only HTML5 really had obsoleted Flash so no one installed it any more.”

As far as I can see, HTML5 in modern browsers has proved much less useful to crooks for writing RCE exploits than Flash. And as far as any iPhone or Andriod user can see, HTML5 is a sufficient replacement…

Bryan

“it’s very often used wishfully”

Indeed likely. Like all those man pages with decade-old ‘depreciated’ annotations.

Note to coders out there: write a small prog that finds and eradicates all Flash installations on a given subnet/Lan/domain. Charge ten bucks a pop. Or a dollar per ‘cleaned’ machine. Or donationware.

Note to Helpy McHelperton: I know that certain AD management tools already do this, but many small networks lack domain controllers (including my home, although a handful of Winboxes isn’t the target clientele).

Peter Waterman

Why is “Hitman Pro Alert from Sophos” hosted on servers that appear to have no connection with Sophos per:

– http://toolbar.netcraft.com/site_report?url=www.surfright.nl

– https://whois.domaintools.com/surfright.nl

Before downloading something from a site, surely there should be some due diligence about the site in question – and anyone can put “a SOPHOS company” under the logo?

Paul Ducklin

Fair question…I probably should have spelled it out explicitly so I’ll do so here: SurfRight *is* a Sophos company :-)

Proof can be found via a sophos.com URL here:

https://www.sophos.com/en-us/press-office/press-releases/2015/12/sophos-acquires-surfright.aspx

M. Wright

Great article and resources. Thank you!

Bubba Gump

This was my concern, too – especially since they are .NL domain servers.

Paul Ducklin

The SurfRight offices are in the Netherlands, thus .NL.

MikeP

I have always had my systems set to show full file extensions and I very strongly recommend that everyone should set their systems likewise, as Paul suggests above. It should be the default setting anyway since there have been other insidious attacks using files with additional extensions, sometimes hidden beyond the right margin by additional spaces before the extra extension appears – watch out for them.

CraigM

Just a question, won’t changing the default application for JS files in windows effectively stop any JS code being executed on a web page, including legitimate JS code?

Paul Ducklin

No, it only stops JavaScript code being run *outside* your browser when you double-click a .JS file.

(If you really need or want to run a .JS file you can still do so: save the file to disk and use the command “wscript filename.js”)

JavaScript *inside* your browser is handled directly by the browser, and is subject to all the limitations (e.g. it can’t access files on your hard disk at all) imposed by the browser’s so-called sandbox.

Matt Zapp

Yes, but try hitting any web page with JS disabled and you will soon find out how widespread its use is in web development.

ParrotLover

The title is a bit misleading isn’t it?

The malware is written in JS, but it does not run when you visit a page due to browser restrictions. The user has to execute the file (via Windows script host) himself or some other way than just browsing some web site.

Paul Ducklin

Errr, the headline says “ransomware that’s 109% pure JavaScript”, and it is (which is, as the article explains, rather unusual).

The deal here is that in Windows, .JS files are effectively first-class applications when run outside the browser.

Not sure how that’s misleading. If it were ransomware that could escape from your browser I’d have used a headline like “ransomware that escapes from your browser” :-)

RichardD

109% pure JavaScript?! :o)

Paul Ducklin

THAT’S HOW PURE IT IS. Typo, sorry about that. I’ll leave it in the original comment because it’s kind of amusing :-)

Anonymous

When Will we see hitman pro (Sophos Clean) integrated in to Sophos end point security ?

Paul Ducklin

I’m not sure of the date, I’m afraid…but it is en route :-) More news when I have it.

MossyRock

Don’t forget that these settings are account-specific. You have to make these changes for EACH account that is on a Windows system.

DMQ

Windows 7 64 bit

Hitman made a complete mess of IE 11 refusing to show last tab, always requiring one blank tab.

On trying to remove it from Control Panel programs/ uninstall, it Blue Screened windows on restart as its .sys driver was ‘still active’.

Removed until product is more reliable.

Paul Ducklin

Sorry to hear you had problems…you don’t say what else was installed, which might be relevant. Have you tried emailing support@hitmanpro.com?

Matt Zapp

Because of it being the most widely used browser its also been the most insecure due to the massive amount of exploits that target it.

Chris

>The AES key downloaded by the malicious JavaScript is only ever kept in memory, so once the encryption is complete and the JavaScript program exits, the crooks have the only remaining copy of the key.

Why does this matter? Unless they download the private key to your machine, you’ll never be able to access the files. Presumably they don’t download the private key to your machine.

Paul Ducklin

There is no “private key” (in the sense of public-private keypair encryption). There’s a unique AES secret key that *is* sent to your computer, but never saved. Good luck finding it memory after the JavaScript ends. (Might be possible! But it might not.)

danpantry

I’m not convinced this is a legit threat, and the title is incredibly sensationalist.

The script here absolutely does require a download; The user would have to *download* the file, then manually open that file (title as of current says “No download required”). If the main reason this is a threat is because the extension is hidden by default, sorry, but .exes do that too.

Additionally, if I am able to access the Windows Script Host on your PC, I can do lots of other nasty things, too.

Now, one thing that might be a concern is that this would potentially slip through the anti-viruses cracks because it’s so unusual, and that would definitely be a good thing to come out of this – but the only novel thing about this attack is that it is in javascript; it still relies on a user to execute an arbitrary file, and if they do that, then any potential attacker can do a lot more damage with any language.

Paul Ducklin

Most ransomware doesn’t work with web links, but rather by email attachments, where the malicious file is sent *to* under cover of being an important document rather than downloaded *by* you. And most ransomware that’s JavaScript based uses the .JS only to fetch the next part of the attack.

The extension issue isn’t “the main reason this is a threat,” but merely a way of understanding how and why someone might open a .JS under the impression it was a document.

Another point we’re making here is the important one of reminding people that JavaScript *isn’t all about your browser* (an impression it’s easy to form), where JavaScript has a well-deserved reputation for being relatively safe. In other words, it’s easy (and not unreasonable) to assume that executing an arbitrary JavaScript file ought to be much safer than running, say, an EXE. In fact, you can do identical damage with both.

I think a lot of people (and perhaps some anti-virus products) have assumed that ransomware will involve an EXE file at some point, and thus that EXE-specific defences are sufficient. This is a real-world reminder that JavaScript alone is enough.

danpantry

Sure, I’ll agree with you that JavaScript isn’t all about the browser (i’m a full stack developer), however this entire threat relies on the premise of running a random file off of the internet, which is bad practice whichever way you spin it, JS or not.

The only thing that is “news” about this is that now AVs are going to have to catch when a JS file is contacting the internet.

Paul Ducklin

Why “are now going to have to”?

(Ironically, the security products that might get caught out would be those that *relied* on waiting for JS files to contact the internet. You can write ransomware that doesn’t need network connectivity at all.)

Matt Zapp

AVG spotted my stupid attempt to hit a url with a similar threat Ransom-JS Troj, I think the good anti virus databases are aware. You are correct though, I would have had to click on a button that was misleading, but the site was that counterfeit microsoft virus removal BS so I knew before I got the alert from AVG, but yes I was surprised AVG picked up the malicious script before it allowed me to connect.

Francis Kim

Microsoft seems like the offender :P