An investigation by the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) is shining a spotlight on a US government program developing algorithms that can identify similar tattoos from images, for use by the FBI and law enforcement.

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) has been conducting research into tattoo recognition technology since 2014, relying on a database of 15,000 tattoo images collected by the FBI from prisoners and arrestees without their consent, according to the EFF.

Tattoos, which are usually elective (people choose their own tattoos), can reveal a person’s cultural, religious and political beliefs, the EFF says, raising concerns about how this technology impacts First Amendment rights to freedom of speech and religion.

The algorithms developed by the NIST could be used by law enforcement to link individuals in gangs, but also people affiliated with the same religious or political groups, the EFF said in a report released last week.

Eventually, the EFF says, the algorithms could be used to track individuals by matching images in a database with images of tattoos captured by police or surveillance cameras.

Many of the tattoos in the FBI database showed Christian or Catholic iconography, such as crosses, rosary beads or images of the crucifixion, which the EFF said was “totally inappropriate.”

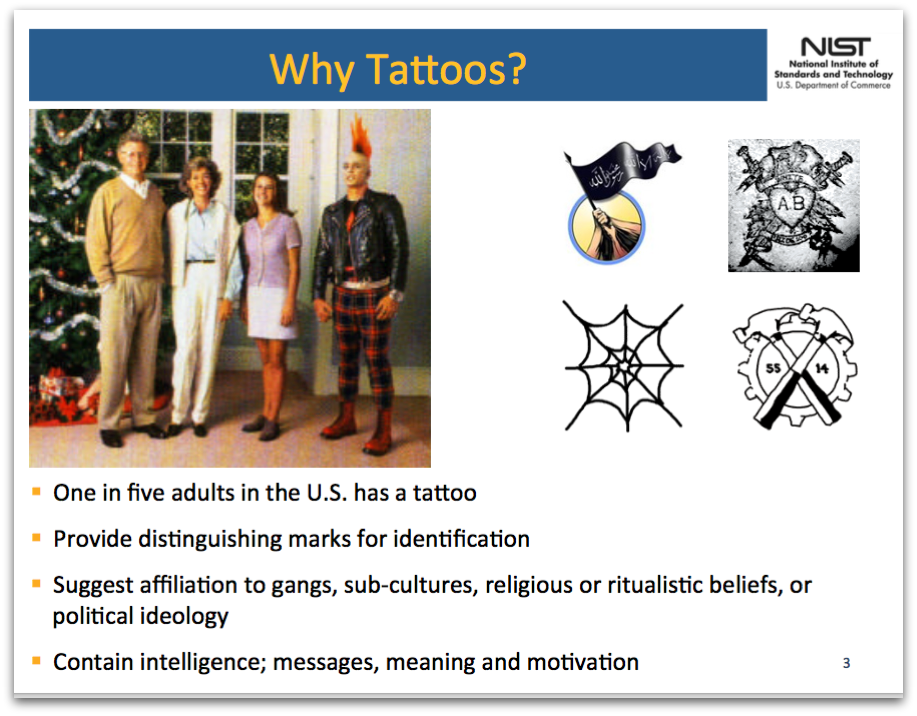

An NIST slide obtained by the EFF through a public records request showed the NIST touted tattoo recognition as a way to link individuals to “gangs, sub-cultures, religious or ritualistic beliefs, or political ideology.”

The EFF also raised concerns about the privacy of individuals whose tattoos were included in the database used in the NIST’s research – not just inmates, but people who were arrested or merely stopped by police.

The tattoo images were shared with private companies such as MorphoTrak, “one of the largest marketers of biometric technology to law enforcement agencies,” including personally identifiable information such as names, faces and birth dates, the EFF report says.

Furthermore, the NIST research is being conducted without scrutiny or ethical oversight, the EFF claims:

Under federal research guidelines, research involving prisoners triggers enhanced scrutiny and ethical oversight to prevent their exploitation. Instead, NIST and the FBI are treating inmates as an endless supply of free data.

In a written response to the EFF report, the NIST said its research will “help ensure tattoo matching technologies are evaluated using sound science to improve accuracy and minimize mismatches.”

Despite the concerns raised by the EFF report about ethical research practices and data sharing, the NIST denied that the FBI tattoo database contained any other identifying information, and said its research does not come under federal regulations for human-subject research.

Another round of NIST research will seek to gather another 100,000 tattoo images collected by police and prison agencies in Florida, Michigan and Tennessee.

The EFF said the government should “act responsibly and halt the program until it goes through the full oversight process.”

Tattoos can already be used by law enforcement to identify individuals, of course, but the use of image recognition technology raises civil liberties concerns about how the images are gathered, used and stored.

Law enforcement agencies are increasingly tracking people by biometrics, whether it’s facial recognition, fingerprints, voiceprints or genetic material including DNA obtained from blood or a person’s unique cloud of microbes.

The FBI and many state and local police departments in the US have for years been creating their own databases of criminal suspects’ DNA, without any kind of regulation or transparency as to how the information should be used or for how long.

The EFF and MuckRock have undertaken a national census to gather public records on what biometric technologies state and local law enforcement agencies have and how they’re using them.

Pat

It would be great if the FBI could stop profiling it’s citizens constantly.

Anonymous

And I’ll bet that if your loved one was murdered by someone who could have been identified by this technology, you’d be the first to sue the legal system for not using it to put the perpetrator away.

KEN

right…..they are trying to make those guys in prison look like criminals.

Richard Klimming

When things like jail and prison sentences were first introduced, it was assumed that, once you had served your time, your debt to society was paid entirely; there was no inability to find employment, and there was no Big Brother watching over your shoulder for the rest of your life afterwards. It’s a shame that, in a civilized society, we don’t work to rehabilitate these people. Instead we confine them to minimum wage jobs that they have no hope of escaping (because who wants to hire someone with a record even though they’ve paid their debt to society and possibly regret it?), and we continue to rob them of their civil rights even after their release.

Anonymous

“It’s a shame that, in a civilized society, we don’t work to rehabilitate these people”

very true.

However this is only a concern for those who allow themselves to fail. I have a friend who served a couple years in prison, and he’s legitimately the most positive and upbeat guy I know. Never having taken a formal survey, I believe the opportunity for turning one’s life around still exists for those willing to seek it.

This article brings to mind the people who view themselves as clever for getting inked with a bar code with a serial number, only to become more familiar down the road with various legal processes.

Like the criminal confessing “privately” on Facebook,these guys are forfeiting their ability to blend in and are saving us time. If I behave I’ve no deterrent to putting Betty Boop on my forehead. …at least not legally.

Mahhn

There is another way to identify people for their “political ideology” Most of the are registered voters and politicians. The FBI should arrest all the politicians.

Jonathan

Perception of security, perception of freedom…perception of security, perception of freedom…

Which one should we choose? Hmmm. They’re both illusions, and everyone sees them differently. I suppose the answer depends on which one is the most profitable. :-P

KEN

collected by the FBI from prisoners and arrestees without their consent, according to the EFF.

right….everyone knows people get tattoos so no one will look at them.

Bryan

If I choose to get a tattoo that’s my choice. But I’d be pretty stupid to expect any LE efforts to avoid taking note of the resultant (usually public) identifying mark. Free speech also includes the right to be silent.

AFA using prisoners as a data supply treasure trove… triple my tax dollars to provide you with perpetual food, shelter, and both better workout equipment and television than I can afford, you’ve forfeited your rights to total privacy–you’ve got the time to participate in a study or two.

jkwilborn

I think most of you are arguing about jail, when the idea is over biometrics. In the US, judges have forced people to unlock their phones because of the older rulings that the police can have access to things like fingerprints, eye color etc… Know as biometrics, but now we’re able to use them as keys and many judges feel it’s like it’s a fingerprint and they can force capitulation. Only difference with tatts is they’re picked out by the user, personal and many don’t want others to know about them. I have tatts, and all of mine are covered, even when I was a police officer there was no knowledge by the department (and I don’t think they cared). This is also a key part of your life, to some and would be no different than looking through your home or cell phone picking up photos or texts. They need to just stop this indiscriminate collection of people data.