A few months ago, a “teen stoner” allegedly hacked into an AOL account belonging to the head of the CIA a few months ago and leaked information about him gleaned from private documents. (In street-speak, this is known as doxing someone.)

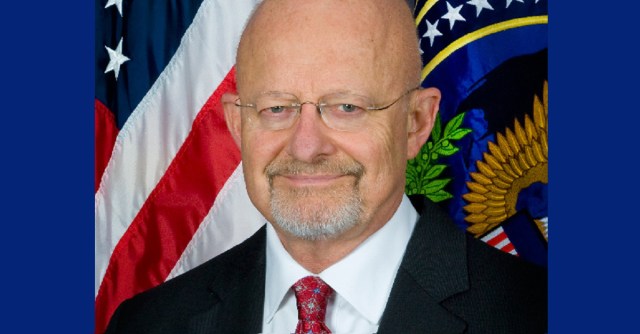

Now he’s claiming to have done the same thing to the country’s top spy, Director of National Intelligence (DNI) James Clapper.

Motherboard says that the alleged hacktivist, known as Cracka, got in touch with the publication on Monday and claimed to have broken into a series of accounts connected to Clapper – including his home telephone and internet, his personal email, and his wife’s Yahoo email.

Cracka is one half of the group CWA (“Crackas With Attitude”), who describe themselves as a duo of pot-smoking, pro-Palestine 13-year-olds, who socially engineered Verizon and got it to reset CIA Director John Brennan’s AOL address in October.

After taking over Brennan’s email, they posted what appeared to be taxpayer and other personal information of more than a dozen top US intelligence officials, plus a government letter about the use of “harsh interrogation techniques” on terrorism suspects.

Brennan called the attack an “outrage” that demonstrates the power of ill-intentioned actors in a cyber-enhanced world.

CNN quoted him:

What it does is to underscore just how vulnerable people are to those who want to cause harm. We really have to evolve to deal with these new threats and challenges.

The FBI subsequently put out a warning about such attacks against politicians and law enforcement officials.

The Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3), a multi-agency task force led by the FBI, issued an alert in November, warning “officers and officials” that they were at risk of having their email accounts compromised and their personal information doxed by “threat actors.”

In this most recent attack, Cracka told Motherboard that while he had control of Clapper’s Verizon FiOS account, he changed the settings so that calls to Clapper’s house number would get forwarded to the Free Palestine Movement, in keeping with the previous, Palestine-themed attack on Brennan.

According to the Guardian, DNI spokesman Brian Hale said in a written statement that the agency is “aware of the matter and [has] notified the appropriate authorities.”

Motherboard followed up by calling a phone number that belongs to Clapper, according to public records.

Reporter Lorenzo Franceschi-Bicchiera’s call did, in fact, get forwarded to Paul Larudee, the co-founder of the Free Palestine Movement. Larudee told Franceschi-Bicchiera that he’d been getting calls for Clapper for an hour and that an anonymous caller told him that he had set Clapper’s number to forward calls to the organization.

Cracka also supplied Motherboard with a call log for Clapper’s home number.

When Franceschi-Bicchiera called one of the numbers, a woman answered and identified herself as an executive at Ball Aerospace and a former senior executive at the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency.

She laughed nervously and hung up.

WHAT TO DO?

Unfortunately, the more information an attacker has, the more convincing a social engineering attack can be.

In this case, both Clapper’s home address and phone number were available through a simple Google search.

To avoid becoming a victim of social engineering or phishing the IC3 offers these tips:

- Be suspicious of unsolicited phone calls, visits, or email messages from individuals asking about employees or other internal information. If an unknown individual claims to be from a legitimate organization, try to verify his or her identity directly with the company.

- Do not provide personal information or information about your organization, including its structure or networks, unless you are certain of a person’s authority to have the information.

- Do not reveal personal or financial information in email, and do not respond to email solicitations for this information. This includes following links sent in email.

- Don’t send sensitive information over the internet before checking a website’s security.

- Pay attention to the URL of a website. Malicious websites may look identical to a legitimate site, but the URL may use a variation in spelling or a different domain (e.g., .com vs. .net).

- If you are unsure whether an email request is legitimate, try to verify it by contacting the company directly. Do not use contact information provided on a website connected to the request; instead, check previous statements for contact information. Information about known phishing attacks is also available online from groups such as the Anti-Phishing Working Group.

- Install and maintain anti-virus software, firewalls, and email filters to reduce some of this traffic.

- Take advantage of any anti-phishing features offered by your email client and web browser.