Here’s a question:

Here’s a question:

Would you install a mobile app that offered smartphone access to a popular online service?

Billions of people do, for example by choosing Twitter’s dedicated mobile app instead of simply accessing the service via their mobile browser.

Ironically, this is quite the opposite of the trend on desktop and laptop computers, where more and more products that would have been standalone software applications in the 1990s or 2000s are delivered as web content, right inside your browser.

As a result, browser security is getting better and better, spurred on at least in part by the increasing number of vendors that depend upon the browser for the security of their own products, and thus for the security of their customers.

But in a second irony, some mobile apps – even ones that only need to support one specific service, and aren’t general-purpose like a browser – are stuck back in the 1990s when it comes to security.

We call this the security gap, where good looks and usability on the small screen of a mobile device often seem to push security into the background.

We’ve written about this problem not only in popular apps such as Pinterest and Yammer (now patched), but even in banking apps, which you’d think would know better.

OK, here’s another question:

Would you install a mobile app that offered extra features for a popular online service?

Millions of people do, for example by using apps like Hootsuite, a popular and perfectly respectable tool for managing your social media accounts in clever ways that software such as Twitter’s regular app doesn’t support.

Most online services have well-defined interfaces, and clearly-arranged legal terms, by which third-party companies can join in the fun, add value for customers, and share in the revenue, rather than becoming competitors instead.

Sounds like a win-win-win situation, and, done properly, it is.

Now for the third question:

How do you tell whether a third-party mobile app company really is “doing it properly”?

For many users, the answer is very simple: stick to the App Store or Google Play.

The impression, if not actually the promise, of Apple’s and Google’s official app outlets, is that software is carefully vetted for security and checked for malware, and thus implicitly safe to use.

And, to be fair, you will be safer and more secure if you stick to the official markets and avoid installing apps from just anywhere.

For example, most of the Android malware we see – and there is a lot of it about! – spreads via alternative markets or through untrusted links spread via mobile messages.

But both Apple and Google have more than a million apps each in their official marketplaces, even though they have been running for under eight years.

Do the arithmetic, and that means they’ve each approved well over 400 apps a day, weekends and holidays included.

So it’s hardly surprising that the vetting process is superficial, at least by human standards, and doesn’t include anything of any substance like a proper code review or a vulnerability assessment.

And that’s how apps like InstaAgent, which promised to help you “see people who viewed your Instgram profile”, managed to get both Apple’s and Google’s imprimatur.

That’s despite prohibited behaviour that included capturing your Instagram login details and sending them off to InstaAgent’s own servers, and then uploading photos to your account to advertise the product.

An independent iOS developer in Germany documented that behaviour, and wrote a compact but informative blog article about it, reaching a pithy conclusion, with which we agree wholeheartedly:

The behaviour of InstaAgent is very, very strange. You should not use the app.

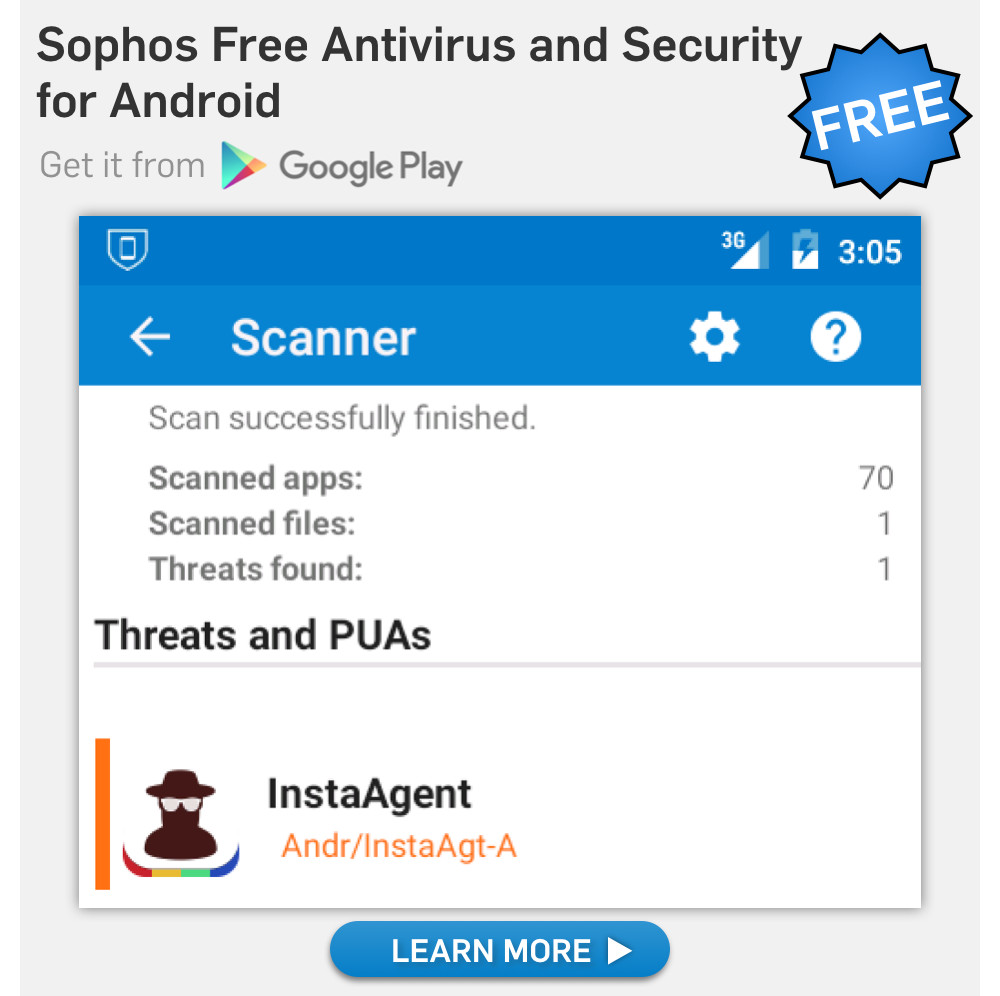

Apparently, both Apple and Google agreed, yanking the offending app (detected by Sophos as Andr/InstaAgt-A) from their respective walled gardens.

According to reports, the app had been downloaded more than 100,000 times from Google Play alone.

At this point, you’re probably asking yourself a fourth question:

Why would a mobile app work this way?

After all, if your app becomes popular and its insecure behaviour becomes known, excommunication from the official market is the most likely result, and that’s all your development wasted.

So why not put in a little bit of extra effort to do things properly in the first place?

Here are three possible reasons:

- You’re an outright crook. Your primary aim is to steal passwords, and so that’s exactly what your app does.

- You’re a programming slob. Instead of using the proper, security-conscious programming interface provided officially by the service, you cut corners by “borrowing” your users’ account details and simply logging in with them.

- You’re a bit of both. You want to offer additional services that can’t be done officially, thus giving yourself an illicit competitive edge over well-behaved apps. Stealing passwords lets you bypass the official restrictions of the service.

All of these reasons end in tears – even the middle one, in which we assume no active malevolence on the part of the developer.

After all, if a developer is sloppy enough to steal your password so he doesn’t have to bother learning the proper way to program, what’s the chance he’ll store your password safely?

In case you’re wondering, the developer of InstaAgent has published an official but almost incomprehensible “issue explanation,” in which he makes a bold but bogus claim that we reject entirely:

Please be relax. Nobody account is not stolen. Your password never saved unauthorized servers. There is nothing wrong.

But also has some advice for other budding mobile app developers that we agree with wholeheartedly:

We have too much excitement and we hurry when our aplication growed. So we couldn't develop controlled enough. And we crashed... Main training in this project for us and other developers, we must full develop with full controlled and full tested before publish an application and first of all we must read service providers policies carefully.

What to do?

If you have ever used the InstaAgent app:

- Uninstall InstaAgent from your phone.

- Avoid apps that offer too-good-to-be-true features.

- Change your Instagram password immediately.

- If you used the same password on any other account…

…but you didn’t do that, did you?

Of course, if you know someone who did share passwords, change those other passwords, too.

This time, choose a different one for each account!

Laurence Marks

The domain host is in Latin America, that hotbed of internet expertise.

R. Dale Barrow

I suspect the code is as sloppy as the English used in the explanation. *shudders*

Mahhn

So much for any reason to trust iTunes and Google Play.

Of course, even without that junk they are still just tracking devices that let us use them as (monitored) communication devices and toys. Meh.