Nothing like the padlock icon showing in your browser window to put your mind at ease, eh?

After all, that lock signifies that the site has a Transport Layer Security (TLS) certificate (TLS being the successor to Secure Sockets Layer, or SSL; it’s also referred to as SSL/TLS).

The certificate authorities (CAs) that give out those certificates are supposed to vet the domains that get those certificates and hence bear that supposedly trusty padlock.

But it looks like the vetting is actually a bit lackadaisical, the result being that typosquatters’s sites are being stamped with TLS certificates they don’t deserve, according to internet services provider Netcraft.

In just one month, Netcraft claims, CAs have issued “hundreds” of certificates for deceptive domain names targeting brands including Paypal, Apple, Bank of America, and UK financial institutions Halifax and NatWest.

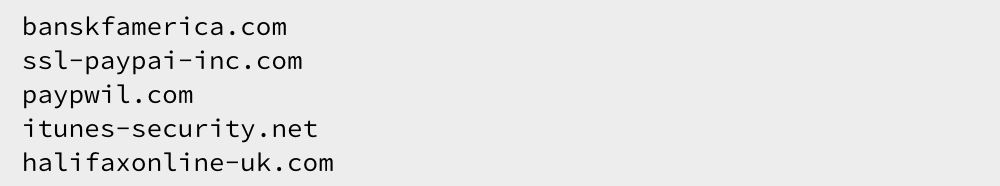

Likely-sounding (but fraudulent) domains that had been issued with TLS certificates and then used in phishing attacks include the following:

A few years ago, Naked Security took a look at what happens when you mistype a website name – easy typos to make, with the resulting URLs being populated by some flavor of fraudster.

The least egregious results of fumbling fingers were links to advertising sites and pop-ups.

The more risky typosquatting URLs were associated with cybercrime, be it hacking, phishing, online fraud or spamming. What’s more, some 2.4% of the domains were devoted to adult or dating sites.

As Netcraft says, sites that use TLS are marketed as trustworthy and operated by legitimate organisations.

The result is that conscientious consumers look for the padlock before they submit sensitive information to websites, including passwords and credit card numbers.

But the fact is that a padlock alone doesn’t imply that a site using TLS can be trusted.

Industry requirements for CAs require that high-risk domain names – i.e., those that may be used for fraud or phishing – be subjected to additional verification.

From the CA/Browser Forum’s Baseline Requirements:

High Risk Certificate Request: A Request that the CA flags for additional scrutiny by reference to internal criteria and databases maintained by the CA, which may include names at higher risk for phishing or other fraudulent usage.

The CA SHALL develop, maintain, and implement documented procedures that identify and require additional verification activity for High Risk Certificate Requests prior to the Certificate’s approval.

Netcraft’s Graham Edgecombe stops short of outright accusing CAs of ignoring checks like these, which are meant to put the kibosh on giving certificates to high-risk sites – say, those that have anything to do with online banking.

But he does point out that some of the CAs’ offerings – including free trial certificates with short expiration times – are quite appealing to phishers:

The short validity periods are ideal for fraudsters as phishing attacks themselves typically have short lifetimes.

Similar issues include one CA’s plan to offer free, automatically-issued certificates later this year.

In other words, there’s not a lot of vetting taking place, Edgecombe told SC Magazine:

The tech industry has been telling users for years, if you want to enter credit card information on a website make sure it's got a padlock, make sure it's using SSL. But now anyone can go and get an SSL certificate for £5 or so, using minimal information, but it's verified.

All the CA will check is that you own the domain name, and that's it. Some of them don't even check that the domain may be misused. One of the rules imposed on certificate authorities is they have to give additional scrutiny to domain names that may be used for fraudulent purposes, but these rules are quite vague.

Edgecombe said that the problem of fake SSL certificates isn’t new, but price competition has caused the cost and levels of checks on certificates to fall.

Meanwhile, phishing is getting smarter, more focused, and even though it’s as old as the hills (at least in internet time), it’s still doing quite well when it comes to putting online consumers at risk.

But just what do we expect the CAs to do, exactly?

Here’s how Paul Ducklin framed it:

If the powers that be accept that I am the guy who owns sn34kydomain.example, then what "vetting" do you expect a CA to do? Why not prevent the domain even being used at all?

In the meantime, this is one more nail in the coffin when it comes to being able to recognise a phishing URL by keeping an eye out for irregularities and mistakes.

Image of phishing courtesy of Shutterstock.com

LonerVamp

The problem here is that these SSL certs are not misnamed or anything. If I make a name like s0ph0s.com and apply for an encryption certificate with the common name s0ph0s.com, who is to say that is a deceptive name before I’ve even done anything with that site?

I know the EV SSL process from 10 years ago was meant to further validate companies, but….

This is sort of like asking gun sellers to not sell to people who will shoot others. How would they know intent? Sure, they can opt to say no, but CAs like Comodo who cold-call my client customer care lines desparately looking for ins to cert buyers don’t surprise me when they’re part of the problem (again).

bob

Interesting. I never realized that having an SSL/TLS certificate was supposed to mean that the site was trustworthy. I just thought it meant that the transport was secure so that no one could snoop between the end user and the website.

And I guess that’s what the criminals are thinking now, too.

Paul Ducklin

Actually, TLS is in many ways much more about *authenticity* than it is secrecy. (If all you want is secrecy of communication, and not to know that you are communicating with the right person, TLS is overkill. You only need a key exchange protocol like Diffie-Hellman-Merkle [qv].)

Indeed, the TLS certificate stuff is all about identifying the other end, and nothing about encrypting the packets you send to it. So you can argue it is vital that the certificates have a clear meaning, and that they genuinely provide accountability by the person they’re issued to.

lee

as long as they are not handing out EV TLS certificate then its not as bad (the general public only look for the padlock or if the whole bar is green, when they should be when on a backing site looking for the Full green bar witch is a EV cert)