Swartz killed himself in January 2013 while facing a laundry list of charges: computer intrusion, fraud, and data theft.

The 24-year-old programmer, a Harvard University researcher at the school’s Center for Ethics, was charged with gaining unauthorized access to MIT’s network (not Harvard’s) to download 4.8 million academic articles from not-for-profit, subscription-based academic journal archive JSTOR, in contravention of his entitlement, with the aim of republishing them without restriction.

The charges stemmed from the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA) – a law that rights groups call “infamously problematic“: a vague, blunt instrument that prosecutors have used broadly to go after behaviours they don’t like, rather than those that actually cause harm.

The charges against Swartz carried a maximum of 35 years in prison, restitution and forfeiture, and a fine of $1 million.

Rep. Lofgren said in a statement that the CFAA is “long overdue” for an overhaul:

At its very core, CFAA is an anti-hacking law. Unfortunately, over time we have seen prosecutors broadening the intent of the act, handing out inordinately severe criminal penalties for less-than-serious violations. It's time we reformed this law to better focus on truly malicious hackers and bad actors, and away from common computer and internet activities.

The proposed overhaul of the CFAA would keep prosecutors from using it to go after things like violating terms of service or the sharing of academic articles.

Rep. Lofgren is backing the House version of Aaron’s Law, while Sens. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) and Rand Paul (R-Ky.) are supporting the Senate’s companion bill. Cosponsors of the legislation also include US Reps. Jim Sensenbrenner (R-Wis.), Mike Doyle (D-Pa.), Dan Lipinski (D-Ill.), Jared Polis (D-Colo.), and Beto O’Rourke (D-Texas).

As Lofgren and Wyden said in a Wired article when Aaron’s Law was first introduced in 2013, as it’s currently written, the CFAA makes it a federal crime to access a computer without authorization or in a way that exceeds authorization.

But Congress never clearly described what that actually means and as a result, the legislators pointed out, “prosecutors can take the view that a person who violates a website’s terms of service or employer agreement should face jail time.”

The potential outcomes are preposterous, they said, and could, at least in theory, be used against kids signing on to Facebook by lying about their age, or against people checking personal email on a work computer.

Under the current CFAA: felony violations. Under the proposed Aaron’s Law: not felony violations.

Instead, the proposed legislation would refocus the CFAA on what it was originally written to address: truly malicious computer attacks, including phishing, malware injection, keyloggers and denial of service attacks.

In a statement, Wyden brought up the government’s hypocrisy when it comes to unauthorised access, referencing a CIA report in which the agency acknowledged that it had spied on the Senate:

Violating a smartphone app’s terms of service or sharing academic articles should not be punished more harshly than a government agency hacking into Senate files. The CFAA is so inconsistently and capriciously applied it results in misguided, heavy-handed prosecution. Aaron’s Law would curb this abuse while still preserving the tools needed to prosecute malicious attacks.

These are the ways that Aaron’s Law would tackle fundamental problems in the CFAA:

- Breaches of terms of service, employment agreements, or contracts would no longer be automatic violations of the CFAA. The particularly problematic lack of definition of “access without authorisation” in the CFAA would be addressed by defining it as gaining unauthorised access to information by circumventing technological or physical controls – such as password requirements, encryption or locked office doors.

- Aaron’s Law would remove a redundant provision that allows individuals to be punished multiple times through duplicate charges for the same violation.

- The CFAA’s tiered penalties have given prosecutors wide discretion to ratchet up the severity of penalties, leaving little room for non-felony charges (i.e., those carrying less than a year in prison). Aaron’s Law would prevent this by disallowing stacking of multiple charges under the CFAA, including state law equivalents or non-criminal violations.

Here’s the text of the bill, and here’s a section-by-section summary.

For a while, this bill looked like it was doomed to wither on the vine as Congress refused to take it up, reportedly afflicted by disinterest and concerns that it went too far in de-fanging the CFAA.

Thank heavens it somehow has struggled to the surface once again.

The CFAA has been broken too long.

Overhaul is overdue.

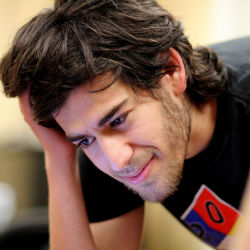

Image of Aaron Swartz from Sage Ross, Wikimedia Commons