Thanks to Rowland Yu of SophosLabs for the behind-the-scenes effort he put into this article.

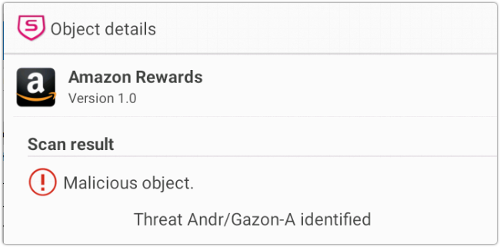

Another Android SMS virus has been doing the rounds, masquerading as an Amazon Rewards app.

Another Android SMS virus has been doing the rounds, masquerading as an Amazon Rewards app.

It’s called Gazon, and it follows in the footsteps of earlier Android viruses like Selfmite and Heart App.

The Heart App story ended quickly and abruptly, with the alleged perpetrator busted by Chinese police in just 17 hours.

It seems he wasn’t a hardened cybercriminal, but a youthful malware creator of the old school, who was bored during his college vacation and wanted to show off at other people’s expense.

As far as we know, the crooks behind Selfmite weren’t quite so obvious about their own identities, and have eluded detection so far.

Viruses and worms…

A virus, remember, differs from the usual sort of malware threat because it doesn’t just infect your device, but can actively distribute itself onwards to infecte others.

In the 1980s and 1990s, most malware was viral, because that was a good way of spreading in the days when many people weren’t on the internet at all, and when most of those who went online did so only intermittently.

Of course, the very act of spreading automatically often made viruses more obvious than their non-self-spreading counterparts (known simply as Trojan Horses, or Trojans).

So, from about 2000 onwards, viruses began to die out because crooks could simply use giant spam runs, or poisoned websites, to trick people into downloading and installing malware, one victim at a time.

SMS viruses

On Android, some malware has combined these techniques in order to create mobile viruses.

Unlike viruses that email a complete copy of themselves as email attachments, this family of malware takes a hybrid approach, sending your contacts an SMS with a link to the virus.

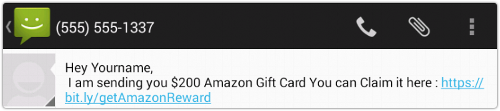

Gazon, for example, arrives like this:

That means the infection can spread even though SMses are limited to less than 200 bytes. (The virus itself is 2.5MB.)

It also means that the poisoned link arrives from someone whose contact list you are part of.

That, in turn, means you’re probably more likely to click the link, even if you’re only thinking of taking a quick look-see.

Protected by Play

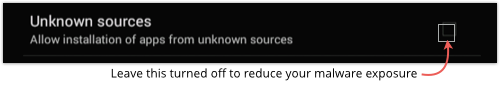

Many of you, especially if you stick to our guidelines, are protected from this sort of infection by Google’s default behaviour of allowing Google Play apps only.

Google Play isn’t immune to malware, but your risk is very much lower if you stick to its vaguely-walled garden.

Google not only performs various security checks before allowing apps into its Play store, but also stands ready to block malicious apps retrospectively.

So even if Google misses a dodgy app at the start, it can change its mind later, stopping any future spread of the malware and withdrawing it from circulation on any devices that have already installed it.

However, reliance only on Google Play doesn’t cut it for everyone, not least in regions like China, where Play doesn’t exist.

The Gazon risk

If you do live your Android life “off-Google,” then you are at risk of malware like Gazon.

If you install it, the icon might give you the impression that it really is all about Amazon Rewards:

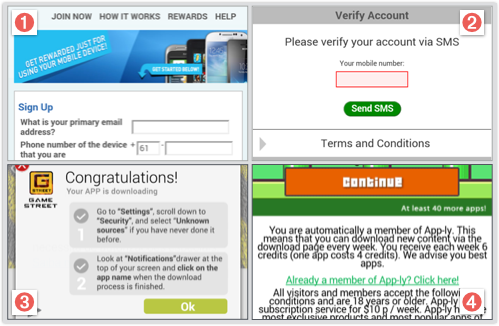

But Gazon’s primary goal seems to be to make cents-at-a-time revenue by taking you to online ads for things reward cards, movie vouchers, free games, and so on.

Sample popups seen by SophosLabs include the following:

The main problem with Gazon, at least for business users, is probably a social one: it aggressively advertises your insecurity to your contacts.

Unlike earlier SMS viruses, it doesn’t limit itself to your top five, or 20, or even 99 contacts: it tells as many people as it can.

That almost certainly includes people who do business with you, as well as just your friends and family.

Do you really want to announce to your customers that your phone is “crook-friendly”?