Old-school computer programmer Olivier Poudade is a French hacker (in the upbeat sense of the word) whose involvement in low, low level coding goes way, way back.

Old-school computer programmer Olivier Poudade is a French hacker (in the upbeat sense of the word) whose involvement in low, low level coding goes way, way back.

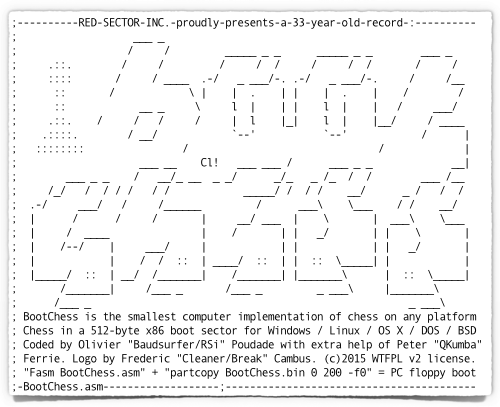

Going as Baudsurfer, he was part of an online community called RSI (Red Sector Inc.), which established what is now claimed as Canada’s first ever BBS, right back in early 1985.

For those who’ve only ever known the internet and the World Wide Web, a BBS is a Bulletin Board System.

That’s a sort-of text-mode website, with news, comments, forums, downloads and more, that you access using a modem on your telephone line.

Unlike the modern internet, where you pay a local company for local access, and from there “fan out” at little or no extra cost to servers all over the world, BBSes were mano a mano affairs.

Each BBS had its own modems and telephone lines that you called up directly, so that local BBSes were cheaper to use than long-distance ones, and much, much cheaper than overseas ones.

Around that time, other aspects of the home computing scene were a bit different, too.

In the UK, for example, the influential and popular ZX81 (sold as the short-lived Timex Sinclair 1000 in the USA) came out of the box with just 1KB of RAM.

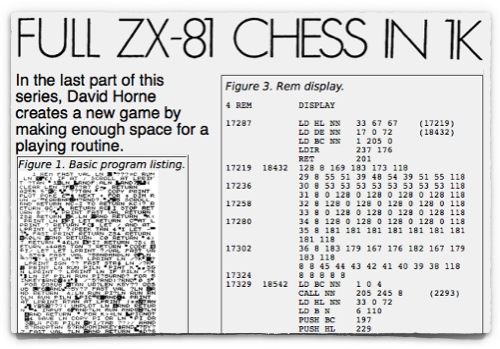

Nevertheless, in 1983, the source code of a chess program was published for the ZX81:

And if that sounds amazing, consider that 1KB was all the RAM that the ZX81 had, leaving just 672 bytes for the chess playing code.

There were certain simplifications, of course.

The program could only play with the white pieces, and you had to prepare two different versions of the game, one for “Queen’s Pawn Moved” and the other for “King’s Pawn Moved.”

In fact, bought copies of the game came on a cassette tape, with the Queen’s Pawn version on one side of the tape and the King’s Pawn version on the other.

And you couldn’t castle, for example.

And you couldn’t castle, for example.

Castling is a special and important move in chess, available only once to each player in each game.

When castling, your king and a rook effectively jump over each other, swapping places in order to shield the king and bring the rook out of its corner and into play.

Because of its significance to chess, and the fact that almost all games include the move, you can argue that a program that omits it isn’t actually playing chess at all, in the same way that a Scrabble game without blank tiles wouldn’t be Scrabble at all.

But a lot of complexity and size (not to mention many bugs) in programming arise from dealing with special cases, and with just 672 bytes to play with, castling had to fall away.

Many years later…

Fast forward almost exactly 25 years, and Olivier Poudade, aka Baudsurfer, thinks he’s cracked the record.

He set a target of 512 bytes – the size of a boot sector.

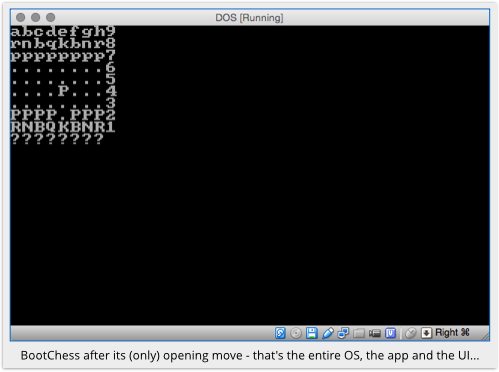

After many iterations, and the help of Aussie anti-virus and machine code expert Peter Ferrie, he delivered BootChess:

You can quite literally write it to the first sector of a USB key, a hard disk or a floppy disk, boot up, and you’re playing.

BootChess is your operating system, your run-time libraries and your application suite, all in one.

Forget GHOSTs (no room), or Heartbleeds (no network) or Shellshocks (no terminal).

It’s Chess, or nothing:

Actually, Poudade’s next challenge is to squeeze BootChess just a little bit more, so that it leaves enough space to be a regularly-formatted, bootable boot sector as well as a chess game.

That way, after playing the game, it could proceed with a normal bootstrap.

The contest

I know exactly what you’re thinking!

What happens if you pit BootChess against 1K ZX Chess?

Sadly, that’s not possible, because both programs can only play with the white pieces.

(Like 1K Chess, BootChess has a hard-coded first move, set to e2-e4, or “King’s Pawn Moved,” as seen above.)

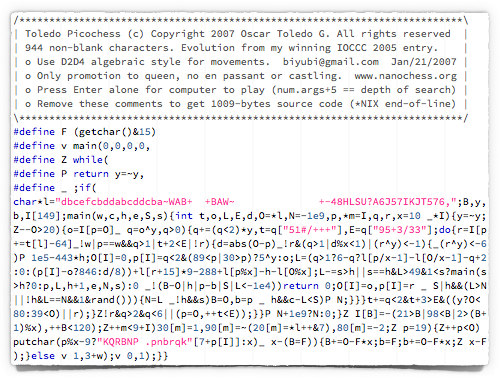

But I did pit BootChess against Oscar Toledo Gutiérrez’s Toldeo Picochess.

Where BootChess fits into 512 bytes of machine code, Picochess fits into 1024 bytes of C source code:

That’s a similarly spectacular achievement – even when redundant characters and comments are stripped from BootChess’s assembly language, you end up with close to 3KB of source code.

What happened?

Chess master Tim Harding is supposed to have said, of 1K ZX Chess, that although it was the work of a genius to make the program fit into the available space, its playing ability was “so appalling that it would be hard to make it beat you.”

Sadly, the same is true of BootChess.

Where Picochess actually managed to develop a few pieces in the course of 12 moves, coming out swinging with a bishop and a queen, BootChess managed little more than advancing several pawns, mostly by one square, and wasting a bishop. (That’s not a phrase you hear often.)

BootChess then proceeded to throw away the game by making an illegal move, failing to notice it was in check.

The bottom line

Apologies to our diehard security readers: there isn’t an obvious security angle here.

Except, of course, that this shows how much you can do in apparently impossibly small amounts of memory, if you are willing to make practicable simplifications, and if you don’t care about correctness.

This is a trick used to good effect by crooks when they have only a tiny hole into which to squeeze an exploit.

Their code doesn’t have to win reliability awards; it doesn’t even have to work all the time.

It just has to work when it runs on your computer, and that’s you pwned…