Here’s a scam.

Here’s a scam.

I email you and tell you that I work for X, one of your suppliers.

X just switched banks, so you should update your database so that future payments no longer go to account Y at bank Z.

Instead, you need to pay them into account P at bank Q.

Then I sit back and wait for the money to roll in.

Heck, I don’t even need to bother with fake invoices, because I just wait for X to send you real invoices and for someone else in your accounts department to approve payment…

…straight into my account.

Then I cut and run, timing my exit from the scene just before X’s debt collector phones you up and asks why you’re behind in your payments.

That would never work!

Of course, that sort of scam would never work.

Companies don’t update their payment records merely on the say-so of a dodgy-looking email.

But what if the crooks behind the scam know enough about you and your company to make their email look non-dodgy?

Even if the crooks aren’t elite enough to hack right into your network (in which case they could probably update your database themselves), what if they have access to a couple of employees’ email accounts?

Or a stash of company paperwork, such as existing invoices showing your payment history – invoices that might not even have been lifted from your network?

Or data about your company that was stolen in an earlier cyberheist by other crooks, who sold it on as a job lot in a so-called data dump for a few dollars per gigabyte?

You can probably imagine just how little data you would need to produce a believable email announcing a bank account change.

For example, perhaps your supplier just moved offices, giving the scammers a hook for their story that would make it sound both informed and reasonable?

(Surely the crooks would only know about the move if they really were staff? Surely it’s plausible that a company would change banks when relocating?)

And perhaps the scammers have access to an email account inside the company, to make their correspondence look legitimate?

Or to a domain they’ve registered that looks very similar to the real thing, such as exannple.com instead of example.com?

Invoice emails scams do work

Sadly, these scams do work, and they have apparently enjoyed a renaissance in recent months.

Indeed, both the Australian Scamwatch team and the US Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3) have put out warnings in the past few days.

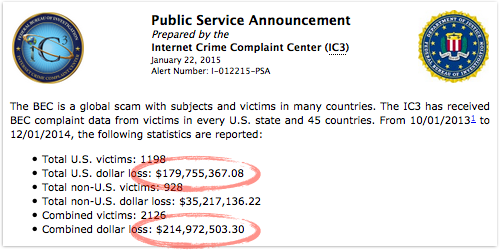

In fact, according to the IC3, the invoice scam, also known as the BEC scam (business email compromise), panned out like this in 2013 alone:

In other words, the average company, once sucked in, ends up losing about $100,000.

And in Australia, the Scamwatch team has received 20 reports in the past three months, a number that equates with about 1000 victims per year in the US, if population is taken into account.

Aussie business have had a slightly better outcome, in some senses of the word “better,” losing about $30,000 on average for a total of $600,000 in the last quarter of 2014.

What to do?

- Revisit your email filtering rules. Getting stricter with sender verification checks such as DKIM and SPF might cause you to start blocking more legitimate email. But if the senders of those emails are also keen on improving security, that might be just the chance you need to start a “win-win” conversation with them.

- Implement a double-approval system for important changes like supplier and customer particulars. Whether you’re paying a supplier, or supplying (or refunding) a customer, you need to make sure that your database is safe against malicious change. Have a second person verify database updates – someone who can ask, “What makes you think this is correct?”

- Don’t rely on verification hints provided online or over the phone. If crooks give you email addresses, phone numbers or URLs to use to “verify” their claims, you will lose if you believe them. If the original email was a bunch of smoke and mirrors, then the “verification” contact information will be smoke and mirrors, too.

- Keep your colleagues up to date with explanations of scams. Many spams, phishes and targeted attacks are really easy to spot – once you know what to look for. You can search Naked Security for the word Anatomy to bring up our series of analytical articles on all aspects of computer security, from malware and exploits to phishing and fraud.

Sophos Naked Security “Anatomy” articles you might like

• iTunes: Anatomy of an iTunes phish – avoid getting caught

• Android: Anatomy of an Android SMS virus

• Bitcoin: Anatomy of a Bitcoin phish – don’t be too quick to click!

• Online banking: Anatomy of a bank scam – spot the Man-in-the-Middle

• For programmers: Anatomy of a buggy pseudorandom generator