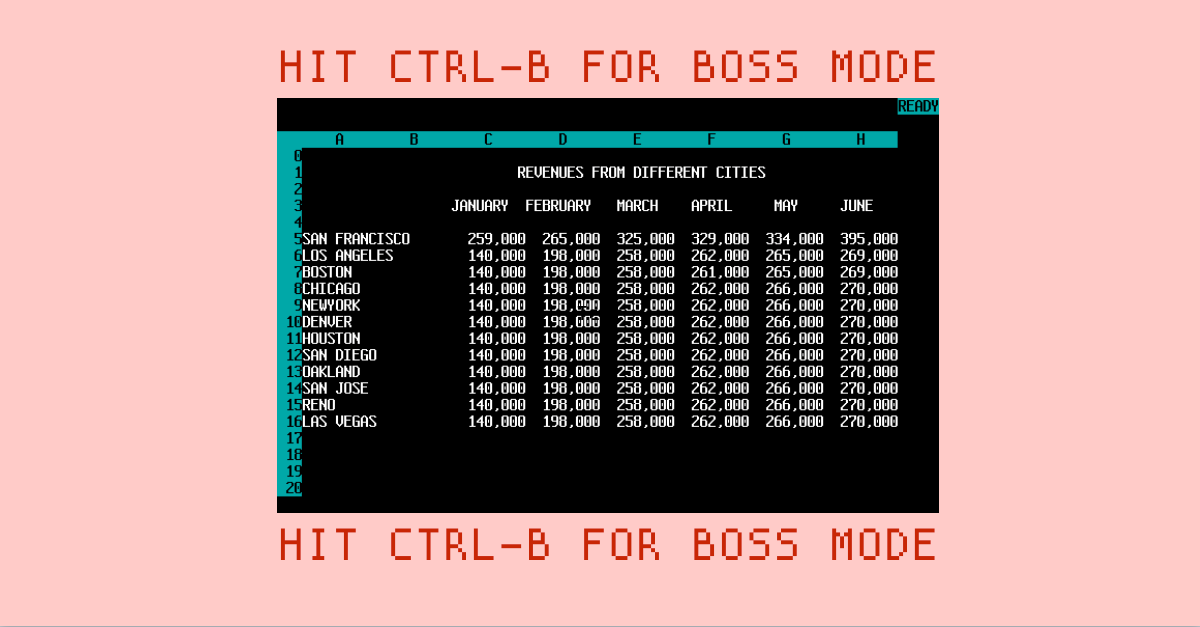

Remember those 1990s MS-DOS computer games that had a “Boss” key?

You could only run one application at a time back then, so if someone came past while you were playing the game on work time you needed a quick way to pop up a fake business app – usually a stripped down spreadsheet program – to act as your “cover story” so you wouldn’t get caught.

(Yes, you recognised it correctly: the Boss screen above is from the original Tetris.)

Fast forward 25 years, and recent revelations from Wikileaks suggest that the CIA has its own modern take on the Boss key.

Apparently, the CIA maintained a list of plausible “cover story” apps that it recommended for field agents who would be working inside a target organisation.

They’re all apps that people might recognise if they saw them running – the sort of app that wouldn’t arouse suspicion, chosen from the list below to blend in best with the field agent’s cover:

VLC Player Portable Libre Office Portable Irfan View Prezi Chrome Portable Babel Pad Opera Portable Notepad++ Firefox Portable Skype ClamWin Portable Iperius Backup Kaspersky TDSS Killer Portable Sandisk Secure Access McAfee Stinger Portable U3 Software Sophos Virus Removal Tool 2048 Thunderbird Portable LBreakout2 Opera Mail 7-Zip Portable Foxit Reader Portable Linux CMD Prompt

Rather than modify the application files themselves, the CIA recommended a trick known as DLL hijacking, which is where you put a specially named DLL into the same folder as an app, so that Windows loads the alternative DLL in preference to the one in the Windows system folder.

DLL is short for dynamic link library, a program component that is stored in a separate file from the main executable.

DLLs exist so that programs can share common “library code”, thus saving disk and memory space, and making updating easier.

As long as the imposter DLL links through to the real DLL, thus duplicating its usual functions, the cover app will run as usual…

…but the imposter DLL will also be running, with the cover app acting as a believable decoy.

Some people are calling this a “vulnerability”, and the attack an “exploit”, but that’s a huge stretch. This method for creating cover-story apps relies not only on how Windows itself handles DLL loading, but also on having field agents who are already in a position to bring in and run any programs they like. Note also that this attack doesn’t require any collusion with programmers inside the companies that make the above products, as some people seem to have assumed. The cover app has to look like the real thing, and the easiest way to do that is simply to start with the real thing. If you can’t find a DLL to hijack, you can just modify the original program instead, or write a “wrapper app” to load your imposter code in the background and run the decoy software on top at the same time.

As it happens, not all system DLLs can be used as imposters: Windows maintains a list of what it calls KnownDlls, such as KERNEL32.DLL and USER32.DLL, that are always loaded from the system directory for performance reasons.

One of the CIA’s favorite imposters seems to be MSIMG32.DLL, a DLL that isn’t common enough to be in the KnownDlls list in any current version of Windows, but is nevertheless common enough to be used by plenty of popular software products.

For this to work, the field agent already needs to be working at a computer inside the target organisation (and in the case of the Sophos Virus Removal Tool, to be logged in as an administrator), running software they brought in themselves.

Why the disguise?

In this “attack”, the field agent already needs the power to do pretty much whatever they want on their computer, including running malware or system snooping tools directly.

So why the subterfuge?

The reason for putting so much effort into the concept of “cover apps” is simply one of blending in, in much the same way that a successful agent would dress, talk and behave in a way that made them fit into the environment where they were working.

This is not about breaking in, it’s about not breaking cover.

Indeed, the CIA called this project Fine Dining, and we’re guessing that’s because most fine dining restaurants have a dress code, so it matters what you look like while you’re there.

So the name is probably a metaphor for eating your fill of other people’s data but looking good while doing it.

The irony here is that it’s almost a backhanded compliment to be on the list: the above apps are there because they’re widely known, trusted and appreciated, so they fit right in.

What to do?

This story is about much more than hacked executables and imposter DLLs: it’s about how to deal with people in your midst who have network powers they don’t deserve, and who aren’t what they seem.

Many organisations quite rightly have a policy of “if you see something, say something”, but to make that work, you also need to have a single IT destination where staff can report potential trouble.

A good place to start is a memorable internal email address such as security911@example.com or tellIT@example.net.

Whether one of your colleagues wants to report a phishing site, a tailgater, or someone who looks as though they’re dining out in a fancy restaurant on the company dime, make it easy for them to remember where to send the information, and make a habit of dealing with security reports promptly.

LEARN MORE: Read our Questions and Answers about Fine Dining ►

Laurence Marks

Duck wrote: “A good place to start is a memorable internal email address such as security911 at example.com or tellIT at example.net.

Sadly, in the large industrial companies those messages would be shunted off to the same offshore locations as regular IT help and nothing useful would come of it.

Paul Ducklin

Hmmm. I hear you. That’s a different problem…but I’m going to add some words to the end of the article about not just listening to users but responding too.

Max

If those agents have privileged access to computers and network, isn’t it likely they are in the IT department? And either way, isn’t it also most likely the IT department that would notice someone acting with elevated privileges and without authorization?

jason brown

Heh, you got downvoted. Must be a couple of spies lurking.