LinkedIn has always been irresistible to cybercriminals and con artists.

The basic lure is the high value of its users. Hack a Facebook account and a criminal will have insight into an account holder’s friends and family. Do the same for a LinkedIn account and they might be able to start mapping relationships inside an entire organisation and its supply chain.

But that’s only the beginning.

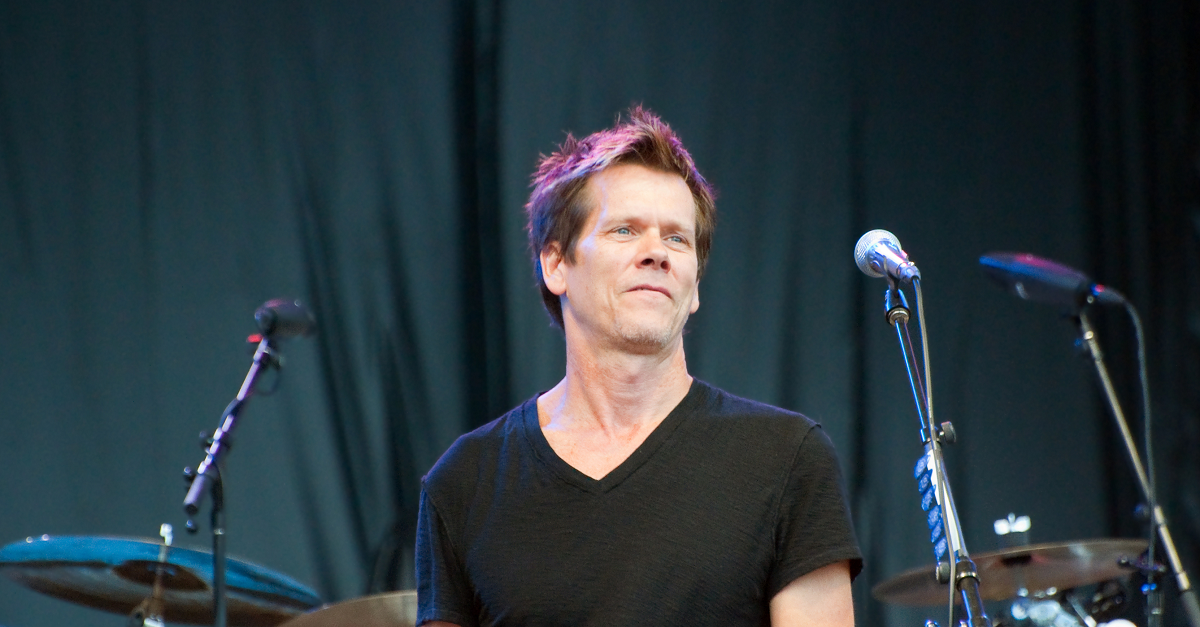

LinkedIn is like a digital demonstration of the famous six degrees of separation from Kevin Bacon rule, which posits that any two people working in Hollywood can be linked to each other through the actor in a maximum of six steps.

Put another way, the fact that you might not see yourself as terribly important in the business world doesn’t alter the fact that you probably know someone who knows someone who is. Every single LinkedIn user has value.

LinkedIn attacks can be internal (within the service) or external (abusing its brand).

The top internal attack is the fake connection request, which exploits the tendency of users to accept invitations from strangers to expand their network. Often couched as marketing or recruitment opportunities, these will typically use profile pictures of women scraped from stock sites.

Fake accounts can be hard to spot at a glance although a giveaway is that they tend to be stuffed full of industry keywords designed to bump them up LinkedIn’s internal search. That’s the other way users might encounter them: when researching new connections.

External attacks are phishing emails that often appear as connection confirmations from unknown LinkedIn users. Confused, the instinctive reaction is to click on the embedded link, which leads to what looks like the genuine LinkedIn site. Logging in hands the credentials to criminals who hijack the account to attack or carry our surveillance on connections.

Controlling visibility

LinkedIn security used to be a labyrinth of privacy, visibility and communication controls but these have recently been simplified.

The key is to tweak account defaults to reduce the attack surface.

- Click on Privacy and Settings (below the profile picture) and study the Profile Privacy tab. The most important setting is who can see connections – changing this to Only You will make it much harder for other LinkedIn users to surveil who you know.

- Make yourself less visible by changing choose who can see you and follow your public updates to Your Connections.

Now to the Communications tab.

- Under who can send you invitations, the recommended setting is everyone. Some users might want to be more circumspect by choosing only people who know your email address.

- Under Messages from Members, LinkedIn offers to filter out certain kinds of contact. It’s probably worth unticking career opportunities and business deals. That won’t stop scammers using this approach but will make their tactic more obvious because it breaches your stated wishes.

Spotting fake users

Security firms lecture people not to connect to strangers but on LinkedIn that’s almost impossible. However, as long as connection requests are studied there are warning signs.

In addition to keyword stuffing and scraped photos, a user with a small number of connections should be viewed as suspicious, as should an incomplete profile and poor spelling.

LinkedIn encourages users to report bogus accounts using the drop down arrow next to that user’s profile.

A final warning: LinkedIn was hacked in 2012 and the account data for 117 million users was stolen, although the extent of the incident only emerged later.

If this doesn’t encourage users to turn on LinkedIn two-step verification (under the Privacy setting), nothing will.

Image of Kevin Bacon courtesy of Paul McKinnon / Shutterstock.com

Anonymous

sure, why be social on a social network? moronic article. If you are that worried about who can see you stay off the site and go back to meeting people the old fashioned way, in person.

Good luck with your job search!

agisten

” tendency of users to accept invitations from strangers to expand their network.”

I have exactly the opposite tendency

Myles

“John E Dunn has covered cybersecurity since 2003, long before anyone was worried. ”

Ha…lol…people were worried far far far before then.