On Friday, one of the largest and most powerful distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks in recent history hit DNS provider Dyn and its customers, impacting major services like Twitter, Reddit and Spotify.

Since then, we’ve heard a lot about what the IoT botnet Mirai and the attack on Dyn was, much of which is guesswork to fill in the blanks.

But in a big and powerful attack like this, it’s just as important to know what it isn’t. So let’s look at some of the assertions and myths that have been doing the rounds.

- Code signing enables these types of attacks and is the work of evil DRM monsters

This is the idea that digital signatures prevent people from authoring replacement firmware to fix this type of bug. This argument doesn’t hold water. Digitally signing firmware is critical for preventing random third parties from updating your firmware with malicious code.

While it is convenient for tinkerers to be able to install their own firmware, people who would do this safely are few and far between.

- The attack against Dyn was caused by tens of millions of connected things

Dyn said on Friday that “At this point we know this was a sophisticated, highly distributed attack involving 10s of millions of IP addresses”. But IP addresses and devices are not one and the same.

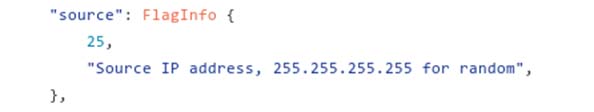

In this screenshot from the source code for Mirai, the botnet can randomize the source IP address. Technically, the attack could have originated from a single device, although many believe the number of devices involved in the attack to be somewhere around 50,000.

Many of us have stressed for years the need to implement RFC 2827 , blocking packets that aren’t part of the expected IP space, to prevent this type of spoofing and help identify affected devices.

Another approach might be implementation of RFC 1149.

- If legislation X in country Y had been passed into law it would have prevented these light bulbs/cameras/cars/thermostats from going rogue

This is an international problem that transcends national borders and laws. Legislation ensuring both minimum safety standards and criminalizing unauthorized access can help prevent, but not resolve, these issues.The devices that have become part of the Mirai botnet are spread around the world and no one government can stop foreign devices from attacking them. The internet is the world’s first truly global space: all the laws, lawsuits and regulations in the world can’t stop this kind of attack.

- Someone should write an anti-botnet worm to patch or even brick all the offending devices

Sadly, nope. First, this is illegal pretty much everywhere, and second, it is nearly always a bad idea from a technical standpoint.The last widespread attempt at this was the Linux.Wifatch worm, which seemed to have been well-intentioned, but, as the EU Agency for Network and Information Security (Enisa) explained at the time, this approach had a number of problems, not the least of which was the potential for the author of the worm to turn it to malicious purposes.

Another problem with this approach is that bricking vulnerable devices could cause further unintended security issues, such as knocking offline internet cameras that are being used to provide public safety functions.

Imagine a situation where, say, an attack on someone went unrecorded because the CCTV camera had been bricked.

- We should recall the affected devices. After all, we recall cars when they can cause public harm

The trouble with the hardware that has been hijacked for Mirai is that the devices are “white label” goods, produced by an unbranded manufacturer for third-party companies.The Chinese company that made the hijacked devices, XiongMai, almost certainly has no way of knowing which companies have rebranded and sold its insecure cameras, and thus who the end users are. That makes it pretty much impossible to recall them.

In any case, how would a “smart” camera or lightbulb display a warning message?

- The answer is product X, which I also happen to sell

Plenty of folks are claiming to have solutions, but there’s a fair chance they’re flogging snake oil.This is a much bigger issue than can be solved by one vendor and one vendor’s products. What’s needed is industry standards and best practices, including thoroughly testing devices for security issues before shipping them to consumers, abiding by best practices and making sure that there is a clear mechanism for patching bugs – and that mechanism must include notifying the owner of the device.

The good news is that there are moves afoot to make this happen. Just last week I was at a meeting arranged by the US Department of Commerce in Austin, Texas, to start building a consensus on what a well-designed mechanism to update IoT devices should look like.

In short, we’re working on this. Watch this space.

Daniel

While signed firmware might not be a valid argument for how attacks like these can be prevented, it also doesn’t work the other way around. A firmware that allows “random third parties” to replace it or inject malicious code, is deeply flawed whether it’s signed or not. Code signing itself verifies the source of the code, and absolutely nothing else, and if we’ve learned anything from experience, it’s that no manufacturer, no matter how big or reputable, can be trusted to write clean or safe code. Signing firmware and allowing unsigned firmware do not have to be mutually exclusive. Automatic, silent firmware updates are probably just as dangerous when they’re signed and from a reputable source, as when they aren’t. And on the pure face of it, DRM and forced signing are just a despicable and incredibly disrespectful way of treating paying customers. A device I buy should be mine to modify as I please, no matter how, why, or what for, and that should be the end of it. Whether “locking down” devices in that way is even legal from a consumer rights perspective will probably keep a few courts occupied in the upcoming years and decades. Allowing unsigned firmware would not help prevent attacks like these, but it most certainly also wouldn’t facilitate them.

FreedomISaMYTH

Or do what i do, when family members buy these totally junk IP Cam/DVR systems I refuse to connect them to the internet, they stay on their own network hardware and never touch anything outside of that. If they ask why they cant view it on the iPhone while shopping for new slippers, I tell them tough ****.

Paul Ducklin

It’s a tough problem, especially with the festive, gift-giving season coming up…

…but stick to your guns :-)

jkwilborn

When one of the HS students tells’em “I can make that work on your phone”, now you have an open one you didn’t know about… :) Not to mention a loss of trust.