Adaptive AI-Native Cybersecurity Platform

Maîtrisez toutes les menaces

Sophos réunit au sein d’une plateforme ouverte des renseignements sur les menaces inégalés, des technologies d’IA adaptatives et une expertise humaine de premier ordre afin de bloquer les attaques avant qu’elles ne passent à l’action. Vous obtenez ainsi la clarté et la confiance nécessaires pour garder une longueur d’avance sur toutes les menaces.

Sophos Firewall

Sophos Firewall v22 maintenant disponible

Sophos Firewall v22 élève l’approche Secure by Design à un niveau supérieur

New Sophos Workspace Protection

Protéger les travailleurs distants et hybrides

MANAGED DETECTION & RESPONSE

Cybermenaces neutralisées, 24h/24 et 7j/7

Votre cyberdéfense 24/7 alliant IA, expertise et renseignements sur les menaces, à laquelle plus de 35 000 organisations font confiance.

Adaptive AI-Native Cybersecurity Platform

Maîtrisez toutes les menaces

Sophos réunit au sein d’une plateforme ouverte des renseignements sur les menaces inégalés, des technologies d’IA adaptatives et une expertise humaine de premier ordre afin de bloquer les attaques avant qu’elles ne passent à l’action. Vous obtenez ainsi la clarté et la confiance nécessaires pour garder une longueur d’avance sur toutes les menaces.

Sophos Firewall

Sophos Firewall v22 maintenant disponible

Sophos Firewall v22 élève l’approche Secure by Design à un niveau supérieur

New Sophos Workspace Protection

Protéger les travailleurs distants et hybrides

MANAGED DETECTION & RESPONSE

Cybermenaces neutralisées, 24h/24 et 7j/7

Votre cyberdéfense 24/7 alliant IA, expertise et renseignements sur les menaces, à laquelle plus de 35 000 organisations font confiance.

Déjouer les cyberattaques

Une technologie de classe mondiale associée à une expertise de terrain, toujours synchronisées, toujours à votre service. C’est notre approche gagnant-gagnant de la cybersécurité.

Une protection résiliente et une plateforme adaptative IA-native pour bloquer les attaques avant qu’elles ne frappent

Une équipe d’experts MDR spécialisés dans la chasse aux menaces pour trouver et déjouer les menaces avec précision et rapidité

Des défenses inégalées pour l’ensemble de la surface d’attaque : postes, pare-feux, messagerie et cloud

Des professionnels de la sécurité de premier plan recommandent Sophos

.webp?width=120&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

.webp?width=440&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

.webp?width=360&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

Bloquez les menaces avant qu’elles ne passent à l’action

Avec Sophos, l’IA évolue avec les menaces et les analystes ne manquent jamais un incident, pour que vous puissiez développer votre activité en toute confiance. Découvrez comment nous protégeons votre entreprise.

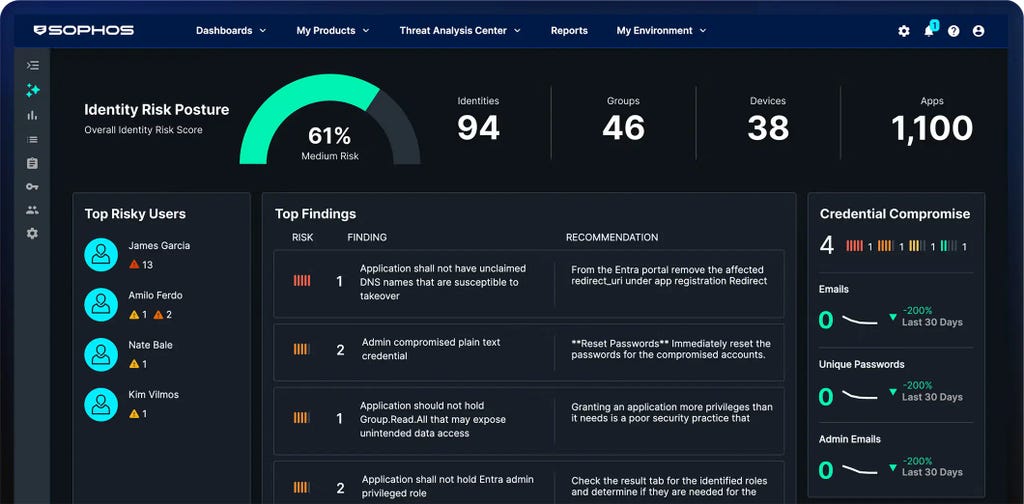

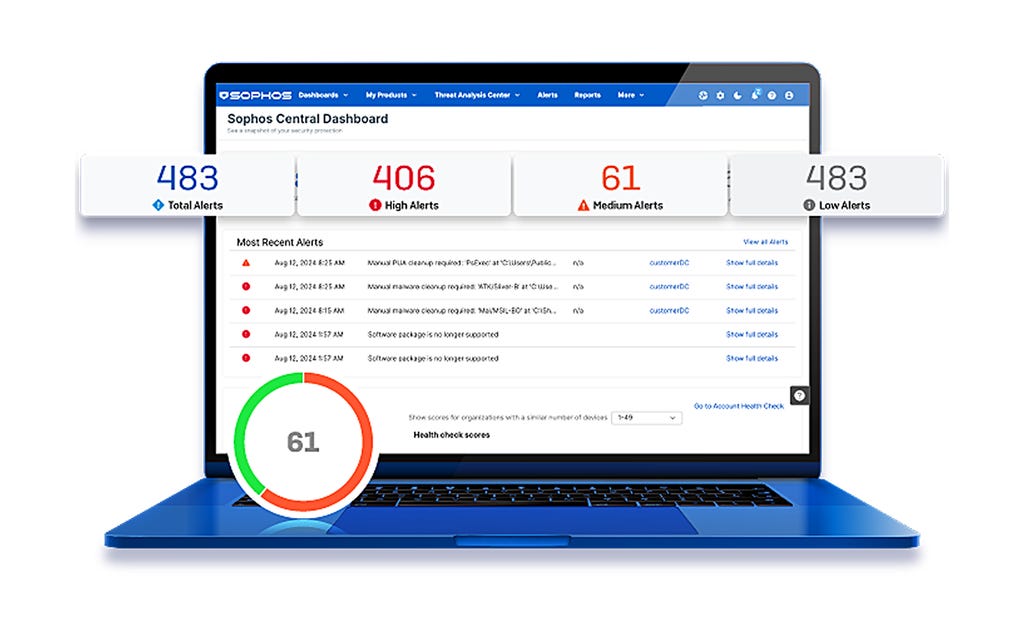

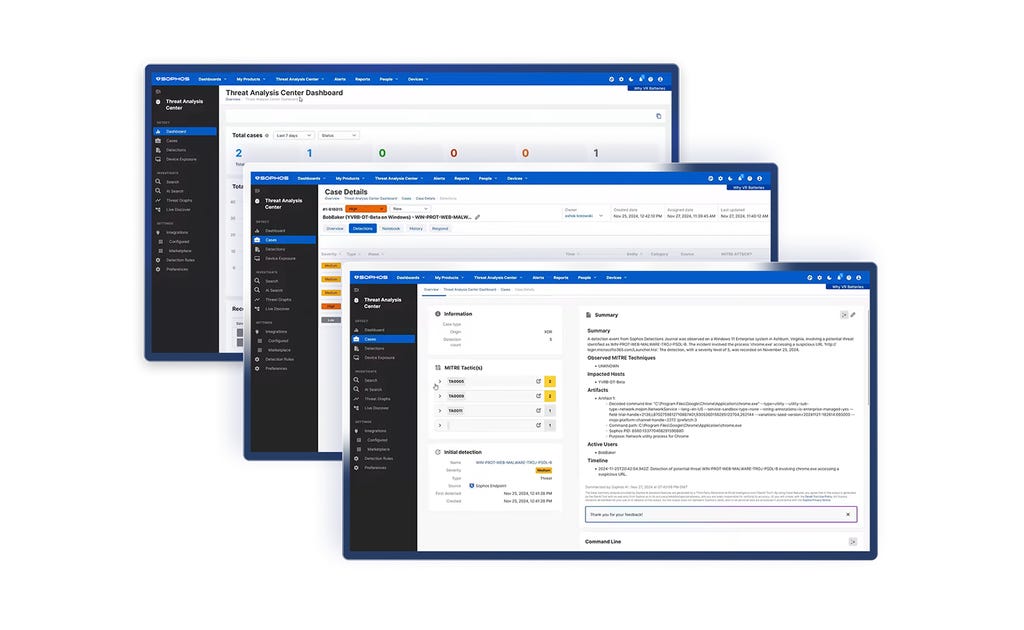

Plateforme de cybersécurité adaptative et IA-native

Sophos Central offre une protection inégalée aux clients et renforce la puissance des défenseurs. Des défenses dynamiques, une IA éprouvée et un écosystème ouvert et riche en intégrations sont réunis dans la plus grande plateforme IA-native de l’industrie.

Sophos vous couvre

Des solutions à vos défis de cybersécurité (si cette expression est trop longue, veuillez utiliser « Solutions de cybersécurité »)

Comment les entreprises assurent

leur sécurité avec Sophos

.webp?width=980&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

Sophos X-Ops

Réunir une expertise approfondie de l’environnement d’attaque pour se défendre contre les adversaires les plus sophistiqués.

Événements et formation

Participez à nos événements en direct ou regardez nos webinaires à la demande pour écouter nos experts en cybersécurité vous présenter les dernières tendances du secteur et nos opportunités commerciales. Accédez à nos formations pour acquérir les compétences et les connaissances nécessaires pour déjouer les cyberattaques.

.svg?width=185&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

.svg?width=13&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

.png&w=1920&q=75)

.png&w=1920&q=75)

.png&w=1920&q=75)