Adaptive AI-Native Cybersecurity Platform

あらゆる脅威を制御する

ソフォスは、卓越した脅威インテリジェンスと、適応型 AI、人間の専門知識を組み合わせたソリューションを、オープンなプラットフォームから提供しています。これにより、脅威を早い段階で阻止するとともに、あらゆる脅威を徹底的に可視化して確実に制御することが可能となります。

Sophos Firewall

Sophos Firewall v22 がリリースされました

Sophos Firewall v22 は、Secure by Design をまったく新しいレベルへと引き上げます

New Sophos Workspace Protection

リモート勤務の従業員を保護

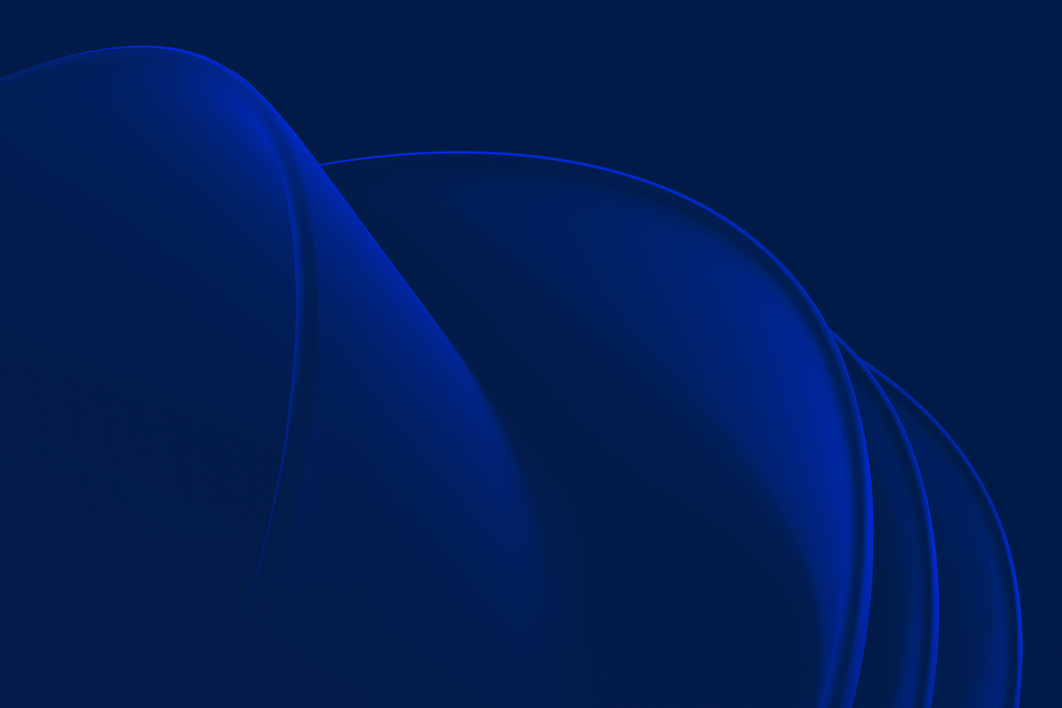

MANAGED DETECTION & RESPONSE

24 時間 365 日体制でサイバー脅威を無害化

AI、脅威インテリジェンス、専門家の力を駆使して、24時間 365日、最前線で防御にあたります。3万 5千を超えるお客様から、高い信頼を得ています。

Adaptive AI-Native Cybersecurity Platform

あらゆる脅威を制御する

ソフォスは、卓越した脅威インテリジェンスと、適応型 AI、人間の専門知識を組み合わせたソリューションを、オープンなプラットフォームから提供しています。これにより、脅威を早い段階で阻止するとともに、あらゆる脅威を徹底的に可視化して確実に制御することが可能となります。

Sophos Firewall

Sophos Firewall v22 がリリースされました

Sophos Firewall v22 は、Secure by Design をまったく新しいレベルへと引き上げます

New Sophos Workspace Protection

リモート勤務の従業員を保護

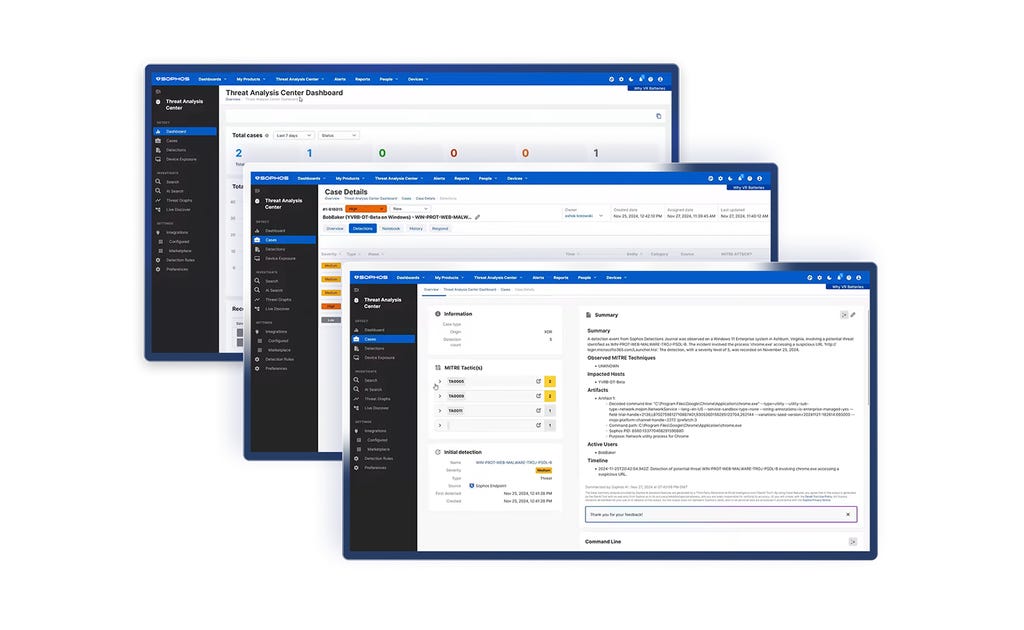

MANAGED DETECTION & RESPONSE

24 時間 365 日体制でサイバー脅威を無害化

AI、脅威インテリジェンス、専門家の力を駆使して、24時間 365日、最前線で防御にあたります。3万 5千を超えるお客様から、高い信頼を得ています。

サイバー攻撃に打ち勝つ

世界トップクラスの技術と実践的な専門知識を常に連携し、常にお客様を守ります。それが、Win/Win実現の鍵なのです。

レジリエンスを追求した保護機能と、AI ネイティブの適応型プラットフォームにより、攻撃を未然に食い止めます

脅威を迅速かつ正確に発見・排除する、MDRの脅威ハンターがお客様をサポートします

エンドポイント、ファイアウォール、メール、クラウドなど、攻撃対象領域全体を保護する優れた防御

セキュリティ業界を牽引する専門家推奨のソフォス

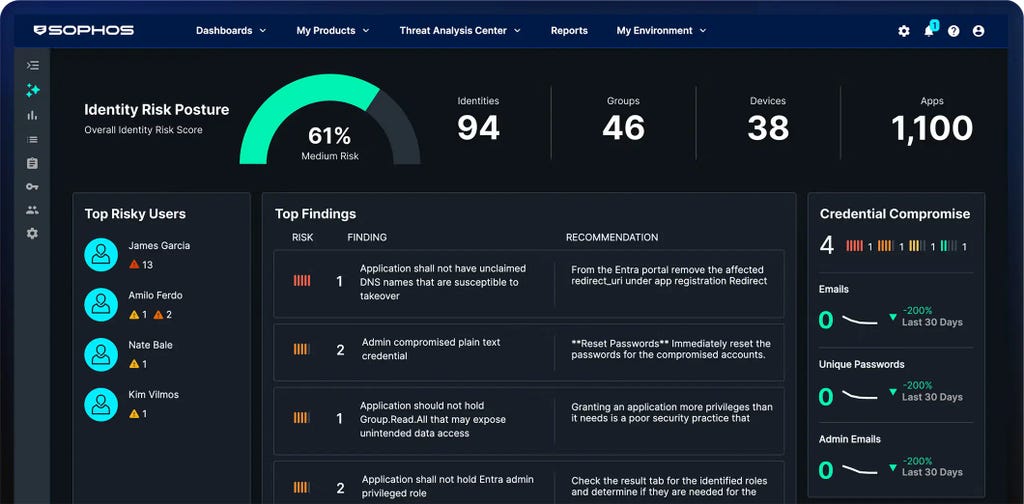

AI ネイティブの適応型プラットフォーム

Sophos Central から、最高水準の保護機能を提供し、防御力を強化します。動的な防御機能と、実績のある AI、サードパーティ製品との連係に対応したオープンなエコシステムを核とし、業界最大級の AI ネイティブプラットフォームを実現しています。

セキュリティソリューション

ソフォスを導入している企業の事例

.webp?width=980&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

Sophos X-Ops

Sophos X-Ops は、サイバー攻撃環境全体にわたる専門知識を結集して、高度な攻撃に立ち向かいます。

ソフォスの最新情報

専門家の話を直接聞けるライブやオンデマンドのイベントにご参加ください。トレーニングを受講して、サイバー攻撃に打ち勝つためのスキルや知識を高めましょう。

.svg?width=185&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

.svg?width=13&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

.webp?width=120&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

.webp?width=440&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

.webp?width=360&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

.png&w=1920&q=75)

.png&w=1920&q=75)

.png&w=1920&q=75)