Adaptive AI-Native Cybersecurity Platform

Take Control of Every Threat

Sophos unites unmatched threat intelligence, adaptive AI, and human expertise in an open platform to stop attacks before they strike — giving you the clarity and confidence to stay ahead of every threat.

Sophos Firewall

Sophos Firewall v22 now available

Sophos Firewall v22 takes Secure by Design to a whole new level

New Sophos Workspace Protection

Protect remote and hybrid workers

A new easy and affordable solution to protect remote and hybrid workers and tackle the challenge of shadow IT

MANAGED DETECTION & RESPONSE

Cyber threats neutralized, 24/7

Your 24/7 frontline defense powered by AI, threat intel, and experts—trusted by 35K+ organizations.

Adaptive AI-Native Cybersecurity Platform

Take Control of Every Threat

Sophos unites unmatched threat intelligence, adaptive AI, and human expertise in an open platform to stop attacks before they strike — giving you the clarity and confidence to stay ahead of every threat.

Sophos Firewall

Sophos Firewall v22 now available

Sophos Firewall v22 takes Secure by Design to a whole new level

New Sophos Workspace Protection

Protect remote and hybrid workers

A new easy and affordable solution to protect remote and hybrid workers and tackle the challenge of shadow IT

MANAGED DETECTION & RESPONSE

Cyber threats neutralized, 24/7

Your 24/7 frontline defense powered by AI, threat intel, and experts—trusted by 35K+ organizations.

Defeat cyberattacks

World-class technology and real-world expertise, always in sync, always in your corner. That’s a win, win.

Resilient protection and an adaptive AI-native platform to stop attacks before they strike

Elite MDR threat hunters to find and defeat threats with precision and speed

Unparalleled defense for the entire attack surface – endpoint, firewall, email, and cloud

Leading security professionals recommend Sophos

.webp?width=120&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

.webp?width=440&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

.webp?width=360&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

Stop threats before

they strike

With Sophos, AI evolves with threats and experts never miss a move, so you can grow with confidence. See how we protect your business.

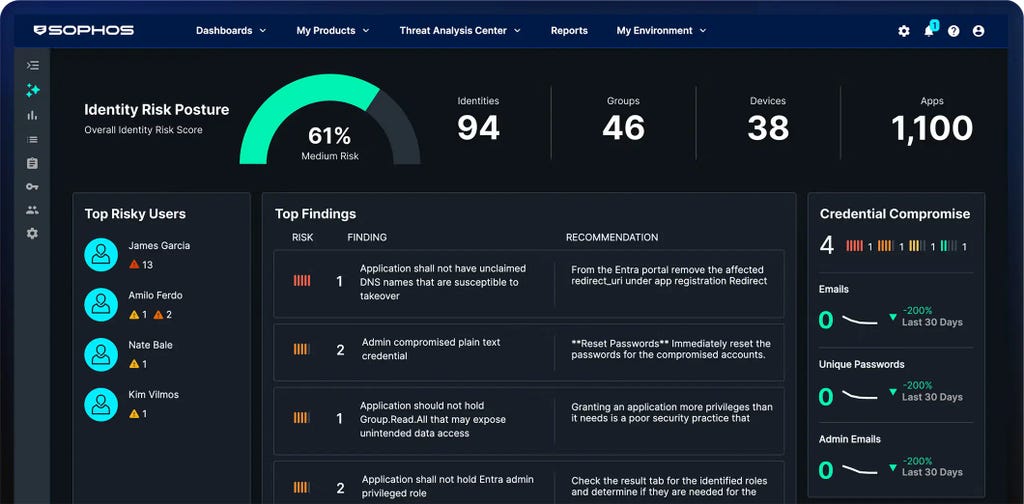

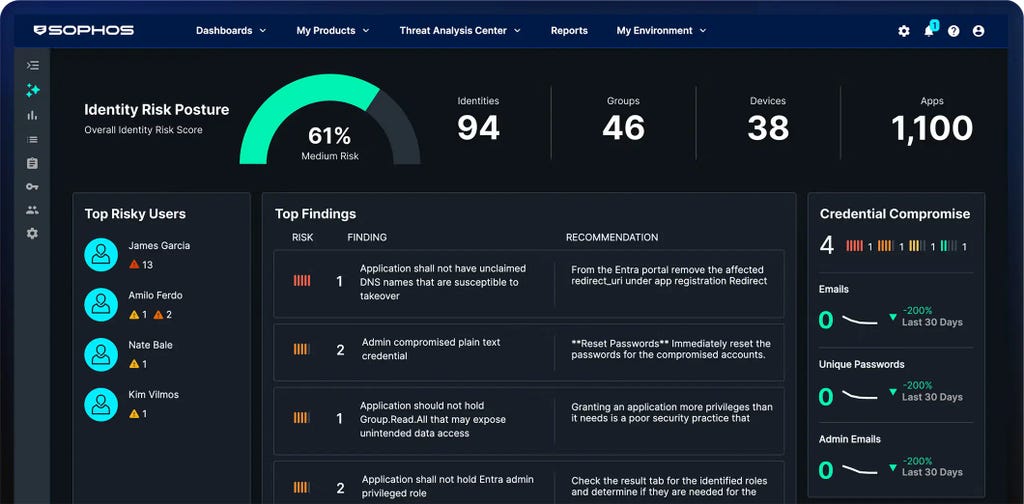

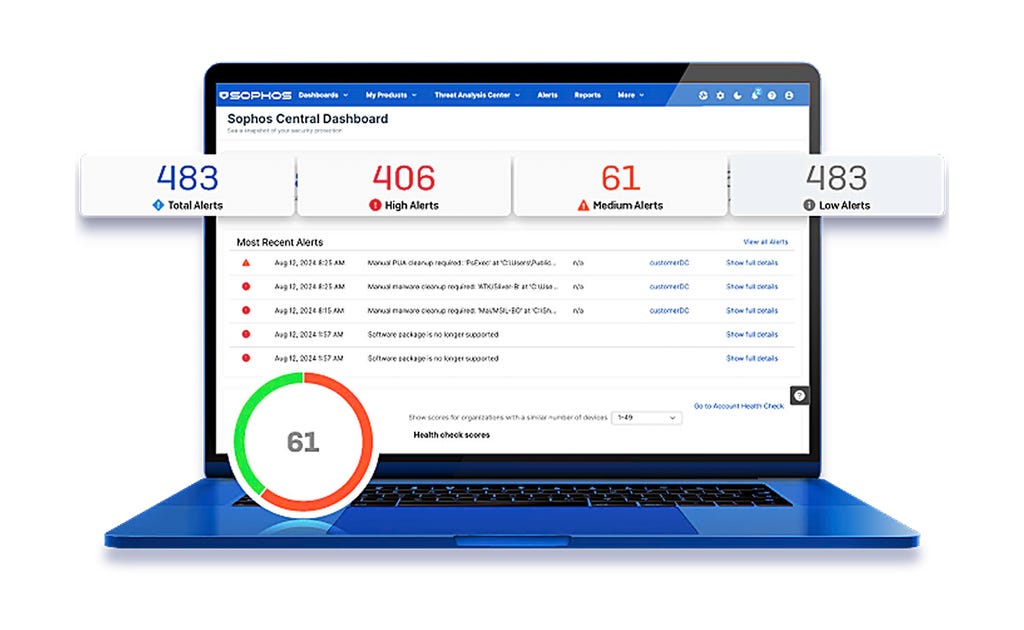

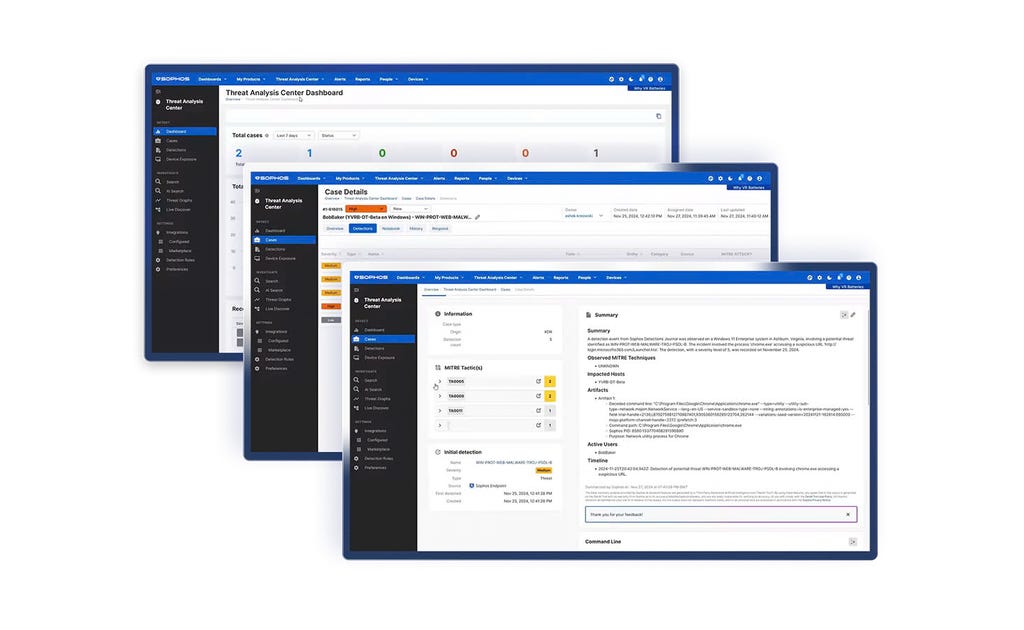

Adaptive AI-native cybersecurity platform

Sophos Central delivers unrivalled protection for customers and enhances the power of defenders. Dynamic defenses, battle-proven AI, and an open, integration-rich ecosystem come together in the largest AI-native platform in the industry.

Sophos has you covered

Solutions to your security challenges

How businesses

stay secure with Sophos

.webp?width=980&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

Sophos X-Ops

Bringing together deep expertise across the attack environment to defend against even the most advanced adversaries.

Events and training

Join us for live and on-demand global opportunities to hear from our subject-matter experts. Access our training to build the skills and knowledge needed to defeat cyberattacks.

.svg?width=185&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

.svg?width=13&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

.webp&w=1920&q=75)

.webp&w=1920&q=75)

.webp&w=1920&q=75)