Adaptive AI-Native Cybersecurity Platform

Tome el control de todo tipo de amenazas

Sophos combina información sobre amenazas sin igual, IA adaptativa y experiencia humana en una plataforma abierta para detener los ataques antes de que se produzcan, lo que le da la claridad y la confianza necesarias para adelantarse a cualquier amenaza.

Sophos Firewall

Ya está disponible Sophos Firewall v22

Sophos Firewall v22 lleva la arquitectura "Secure by Design" a un nivel completamente nuevo

New Sophos Workspace Protection

Proteja a los empleados remotos e híbridos

MANAGED DETECTION & RESPONSE

Ciberamenazas neutralizadas 24/7

Defensa de primera línea 24/7, basada en IA, información sobre amenazas y un equipo de expertos, en la que confían más de 35 000 organizaciones.

Adaptive AI-Native Cybersecurity Platform

Tome el control de todo tipo de amenazas

Sophos combina información sobre amenazas sin igual, IA adaptativa y experiencia humana en una plataforma abierta para detener los ataques antes de que se produzcan, lo que le da la claridad y la confianza necesarias para adelantarse a cualquier amenaza.

Sophos Firewall

Ya está disponible Sophos Firewall v22

Sophos Firewall v22 lleva la arquitectura "Secure by Design" a un nivel completamente nuevo

New Sophos Workspace Protection

Proteja a los empleados remotos e híbridos

MANAGED DETECTION & RESPONSE

Ciberamenazas neutralizadas 24/7

Defensa de primera línea 24/7, basada en IA, información sobre amenazas y un equipo de expertos, en la que confían más de 35 000 organizaciones.

Derrote los ciberataques

Tecnología de clase mundial y experiencia del mundo real, siempre sincronizadas, siempre a su lado. Todos salimos ganando.

Una protección resiliente y una plataforma adaptativa nativa de IA para detener los ataques antes de que se produzcan

Un equipo de expertos en MDR especializados en la búsqueda de amenazas las encuentran y neutralizan con precisión y rapidez

Defensa sin precedentes en toda la superficie de ataque: endpoints, firewall, correo electrónico y la nube

Los profesionales de la seguridad recomiendan Sophos

.webp?width=120&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

.webp?width=440&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

.webp?width=360&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

Detenga las amenazas antes de que le ataquen

Con Sophos, la IA evoluciona al ritmo de las amenazas y a los expertos no se les escapa nada, para que pueda crecer con confianza. Descubra cómo protegemos su negocio.

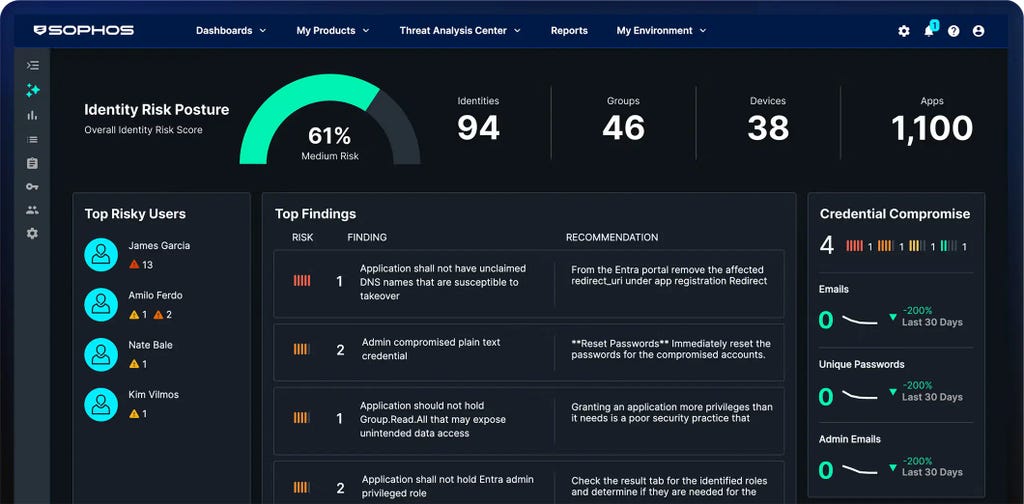

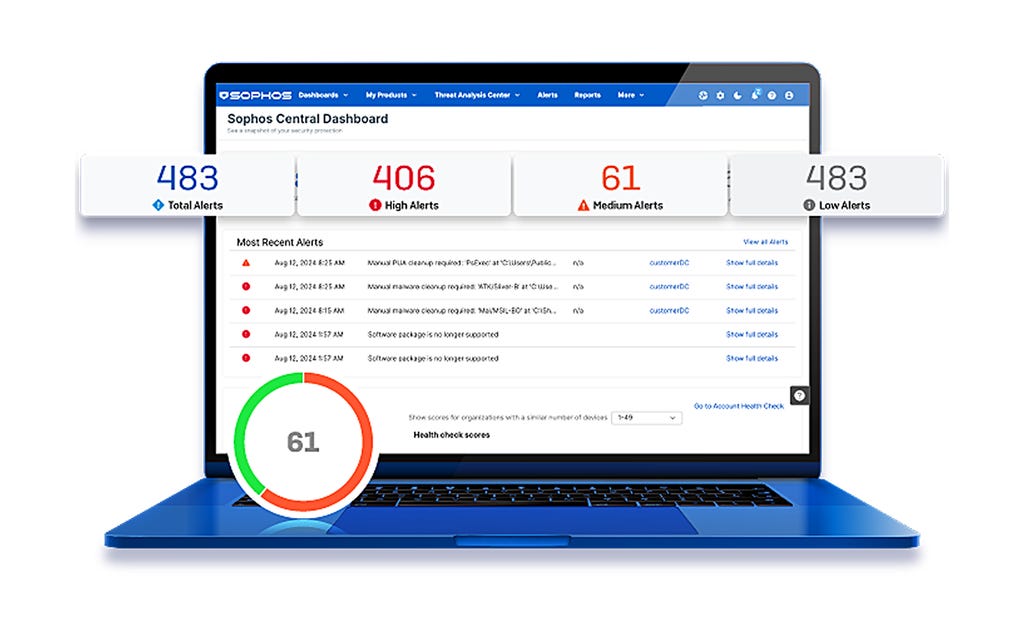

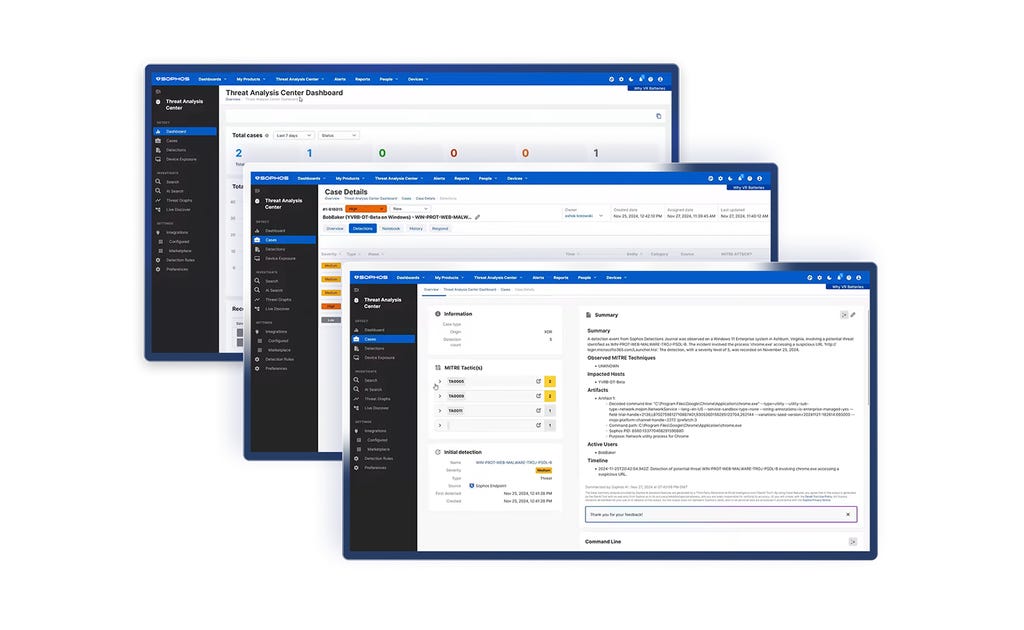

La plataforma de ciberseguridad adaptativa nativa de IA

Sophos Central ofrece una protección inigualable a los clientes y potencia la capacidad de los defensores. Esta plataforma nativa de IA, la más amplia del sector, combina unas defensas dinámicas, una IA probada en situaciones reales y un ecosistema rico en integraciones.

Soluciones a sus retos de seguridad

Cómo las empresas se

protegen con Sophos

.webp?width=980&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

Sophos X-Ops

Benefíciese de nuestra amplia experiencia en todo el entorno de ataque para protegerse de los adversarios más avanzados.

Eventos y formación

Asista a nuestros eventos en directo o vea nuestros webinars bajo demanda para conocer las últimas tendencias del sector y las oportunidades de negocio de la mano de nuestros expertos en ciberseguridad. Consulte nuestra formación para desarrollar las competencias y los conocimientos necesarios para derrotar los ciberataques.

.svg?width=185&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

.svg?width=13&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

.png&w=1920&q=75)

.png&w=1920&q=75)

.png&w=1920&q=75)