Adaptive AI-Native Cybersecurity Platform

Assuma o controle de cada ameaça

A Sophos congrega inteligência de ameaça inigualável, IA adaptável e expertise humana em uma plataforma aberta para interromper ataques antes que se concretizem, dando a você a clareza e confiança de estar no comando de cada ameaça.

Sophos Firewall

Sophos Firewall v22 já disponível

O Sophos Firewall v22 leva os princípios Secure by Design a um novo patamar

New Sophos Workspace Protection

Proteja trabalhadores remotos e híbridos

MANAGED DETECTION & RESPONSE

Ameaças cibernéticas neutralizadas todos os dias do ano

A linha de frente da sua defesa 24/7 com o poder da IA, inteligência de ameaça e especialistas — e a confiança de mais de 35 mil organizações.

Adaptive AI-Native Cybersecurity Platform

Assuma o controle de cada ameaça

A Sophos congrega inteligência de ameaça inigualável, IA adaptável e expertise humana em uma plataforma aberta para interromper ataques antes que se concretizem, dando a você a clareza e confiança de estar no comando de cada ameaça.

Sophos Firewall

Sophos Firewall v22 já disponível

O Sophos Firewall v22 leva os princípios Secure by Design a um novo patamar

New Sophos Workspace Protection

Proteja trabalhadores remotos e híbridos

MANAGED DETECTION & RESPONSE

Ameaças cibernéticas neutralizadas todos os dias do ano

A linha de frente da sua defesa 24/7 com o poder da IA, inteligência de ameaça e especialistas — e a confiança de mais de 35 mil organizações.

Vence a luta cibernética

Tecnologia de classe mundial e conhecimento do mundo real, sempre em sincronia, sempre ao seu lado. Isso é uma vitória, vitória.

Proteção resiliente e uma plataforma de IA nativa adaptável para interromper ataques antes do golpe

Caçadores de ameaças elite do MDR que encontram e vencem as ameaças com precisão e velocidade

Defesa sem igual de toda a superfície de ataque — endpoint, firewall, e-mail e nuvem

Profissionais de segurança de ponta recomendam a Sophos

.webp?width=120&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

.webp?width=440&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

.webp?width=360&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

Bloqueie as ameaças

antes do golpe

Na Sophos, a IA evolui no ritmo das ameaças e os especialistas não perdem nada, o que reforça a sua confiança. Veja como protegemos o seu negócio.

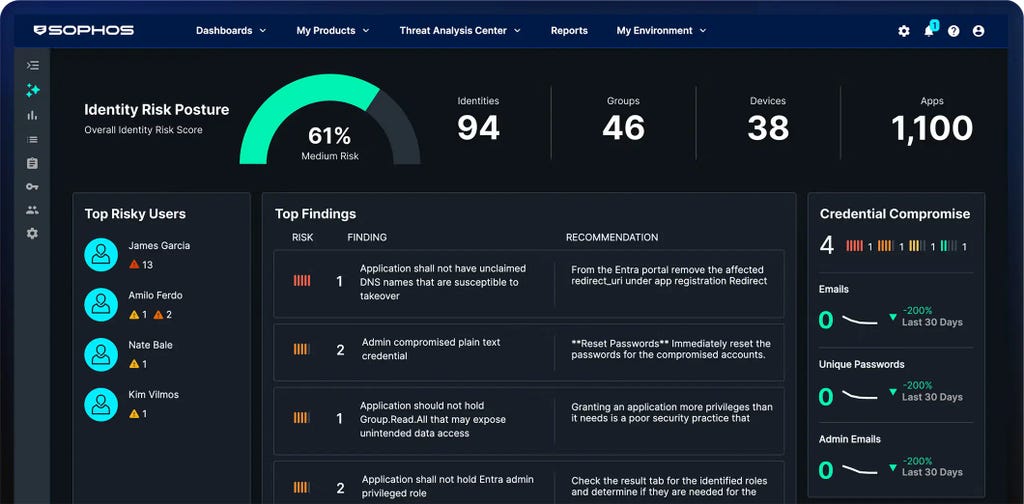

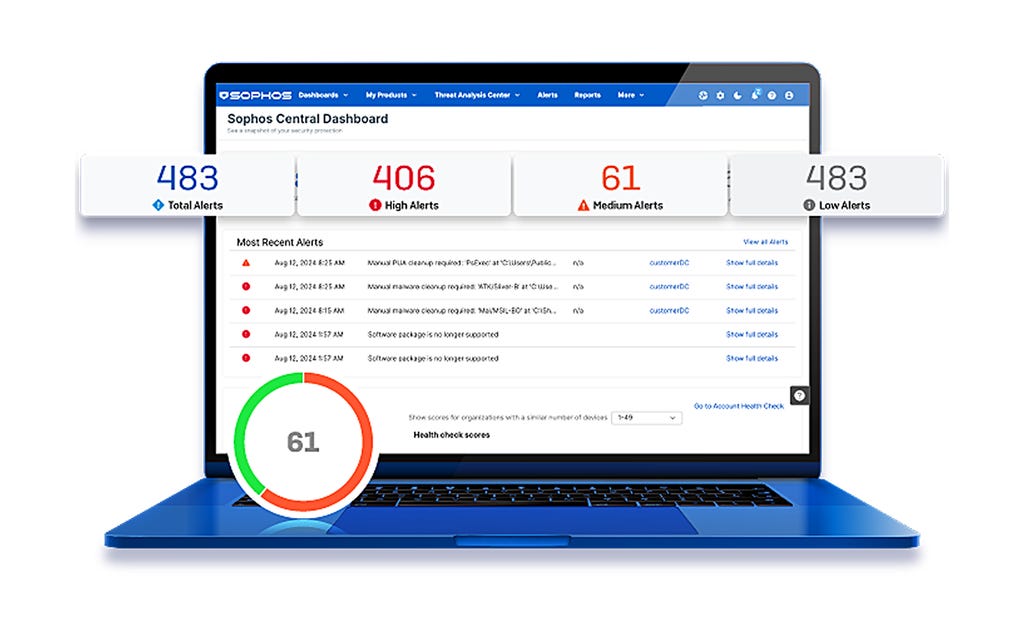

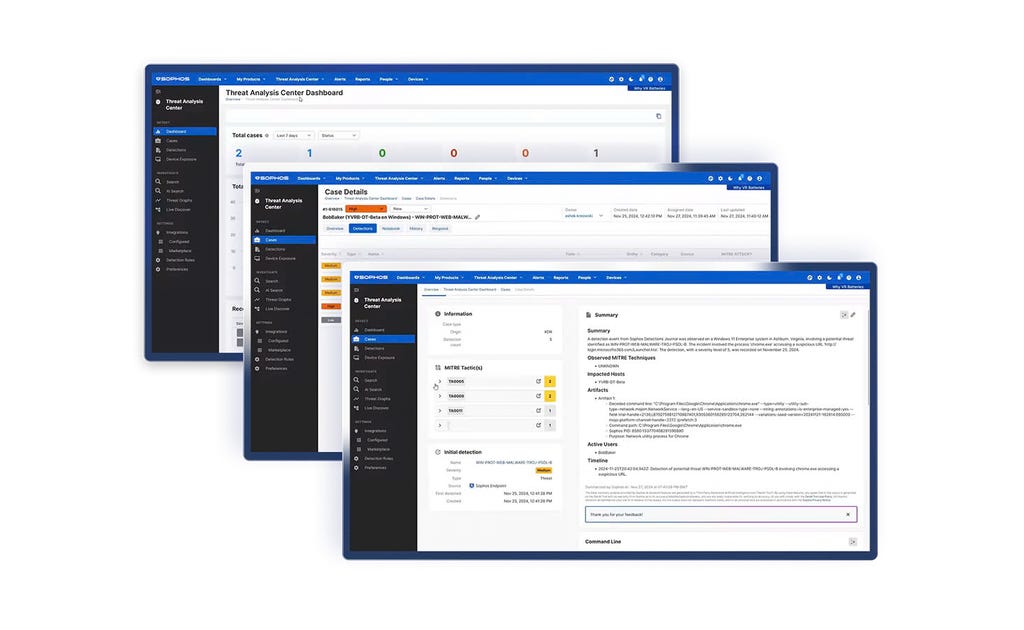

Plataforma de segurança cibernética com IA nativa adaptável

O Sophos Central proporciona uma proteção sem igual para os clientes e aumenta o poder das equipes de defesa. Defesas dinâmicas, IA pronta para o combate e um ecossistema aberto e altamente integrado se unem na maior plataforma de IA nativa do setor.

Sophos sempre presente

Soluções para seus desafios de segurança

Como as empresas se mantêm

protegidas com a Sophos

.webp?width=980&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

Sophos X-Ops

Perícia extrema injetada a todo o ambiente sob ataque para a defesa contra os adversários mais avançados.

Eventos e treinamento

Participe conosco de oportunidades globais ao vivo e sob demanda e aprenda com nossos especialistas. Acesse nosso treinamento para adquirir os conhecimentos e habilidades necessários para vencer os ataques cibernéticos.

.svg?width=185&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

.svg?width=13&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

.webp&w=1920&q=75)

.webp&w=1920&q=75)

.webp&w=1920&q=75)