Adaptive AI-Native Cybersecurity Platform

Assumi il controllo su tutte le minacce

Sophos offre la combinazione ottimale tra dati di intelligence sulle minacce, IA adattiva e competenze umane che non hanno rivali, tutti disponibili attraverso una piattaforma aperta, con la quale puoi bloccare le minacce prima ancora che possano attaccarti. Avrai così massima chiarezza e piena fiducia nelle tue capacità, e potrai tenerti sempre un passo avanti rispetto a qualsiasi minaccia.

Sophos Firewall

È ora disponibile Sophos Firewall v22

Sophos Firewall v22 sviluppa e migliora ulteriormente l’approccio Secure by Design

New Sophos Workspace Protection

Proteggi i dipendenti remoti e ibridi

MANAGED DETECTION & RESPONSE

Neutralizza le cyberminacce 24/7

La tua difesa di prima linea con tecnologie di IA, dati di intelligence sulle minacce ed esperti a tua disposizione 24/7. È la soluzione a cui si affidano più 35.000 organizzazioni in tutto il mondo.

Adaptive AI-Native Cybersecurity Platform

Assumi il controllo su tutte le minacce

Sophos offre la combinazione ottimale tra dati di intelligence sulle minacce, IA adattiva e competenze umane che non hanno rivali, tutti disponibili attraverso una piattaforma aperta, con la quale puoi bloccare le minacce prima ancora che possano attaccarti. Avrai così massima chiarezza e piena fiducia nelle tue capacità, e potrai tenerti sempre un passo avanti rispetto a qualsiasi minaccia.

Sophos Firewall

È ora disponibile Sophos Firewall v22

Sophos Firewall v22 sviluppa e migliora ulteriormente l’approccio Secure by Design

New Sophos Workspace Protection

Proteggi i dipendenti remoti e ibridi

MANAGED DETECTION & RESPONSE

Neutralizza le cyberminacce 24/7

La tua difesa di prima linea con tecnologie di IA, dati di intelligence sulle minacce ed esperti a tua disposizione 24/7. È la soluzione a cui si affidano più 35.000 organizzazioni in tutto il mondo.

Defeat cyberattacks

Tecnologia di primissima categoria e competenze pratiche, sempre sincronizzate, sempre al tuo fianco. Una situazione vantaggiosa per tutti.

Una protezione resiliente e una piattaforma adattiva AI-native per bloccare qualsiasi attacco prima che sia troppo tardi

Esperti Threat Hunter che scovano, combattono e sconfiggono le minacce con accuratezza e rapidità

Una difesa senza pari per l’intera superficie di attacco: endpoint, firewall, e-mail e cloud

Scopri perché i professionisti della cybersecurity consigliano Sophos

.webp?width=120&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

.webp?width=440&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

.webp?width=360&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

Blocca le minacce prima

che possano colpire

Con Sophos, l’IA si evolve insieme alle minacce, così niente sfugge ai nostri esperti. Questo significa che puoi concentrarti sulla crescita della tua azienda, con piena fiducia e serenità. Scopri come proteggiamo la tua azienda.

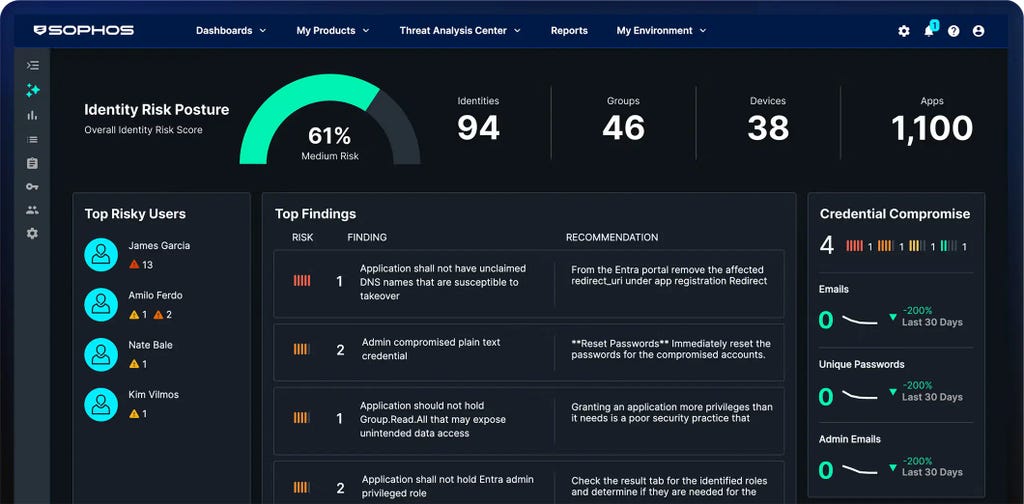

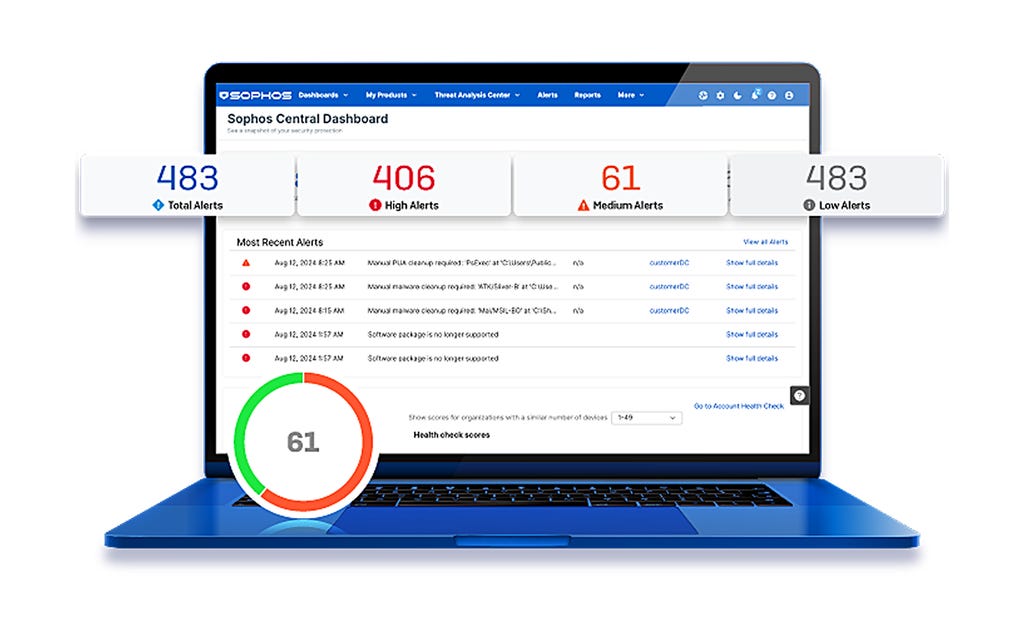

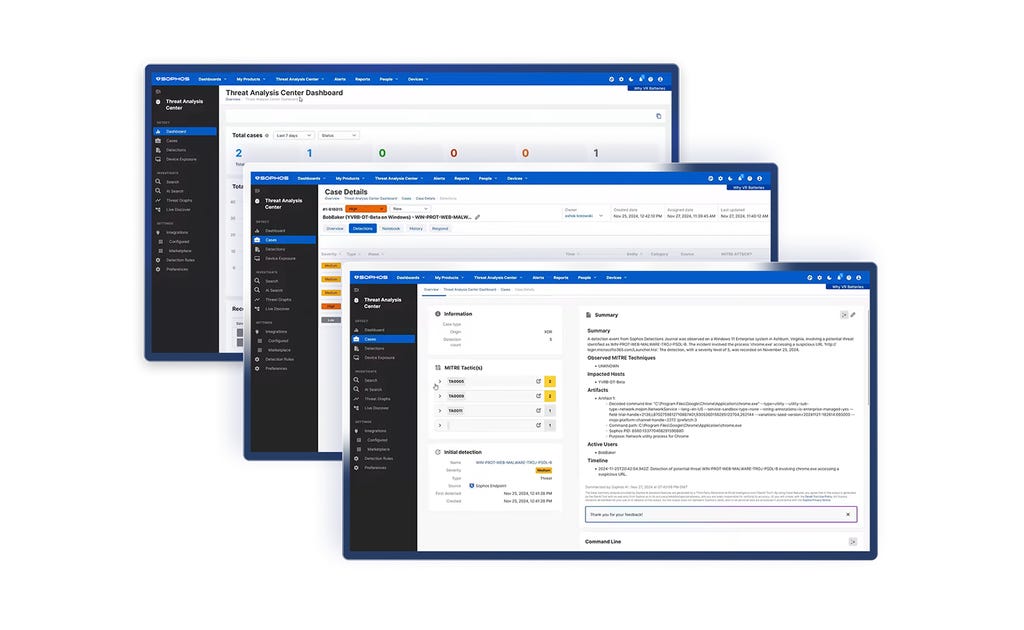

La piattaforma di cybersecurity adattiva AI-native

Sophos Central offre ai clienti una protezione senza paragoni e aumenta il potenziale dei team di sicurezza interni delle organizzazioni. Difese dinamiche, IA dall’efficacia confermata durante attacchi reali e un ecosistema ricco di integrazioni convergono nella più estesa piattaforma AI-native del settore.

Sophos ti protegge su tutti i fronti

Soluzioni ideali per le sfide di sicurezza che affronti

Ecco come le aziende

rimangono protette con Sophos

.webp?width=980&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

Sophos X-Ops

L’unione di diversi ambiti di esperienza per coprire l’intero panorama degli attacchi e proteggerti da tutti i cybercriminali, anche quelli più sofisticati.

Eventi E Formazione

Partecipa ai nostri eventi live e on-demand, per seguire gli interventi dei nostri esperti a livello internazionale. Accedi ai nostri corsi di formazione per acquisire le conoscenze e le competenze necessarie per neutralizzare gli attacchi informatici.

.svg?width=185&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

.svg?width=13&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

.png&w=1920&q=75)

.png&w=1920&q=75)

.png&w=1920&q=75)