Adaptive AI-Native Cybersecurity Platform

Behalten Sie jede Bedrohung im Griff

Sophos vereint modernste Threat Intelligence, adaptive KI und menschliche Expertise in einer offenen Plattform, um Angriffe zu stoppen, bevor Schaden entsteht.

Sophos Firewall

Jetzt verfügbar: Sophos Firewall v22

Sophos Firewall v22 bringt „Secure by Design“ aufs nächste Level

New Sophos Workspace Protection

Schutz von Remote- und Hybrid-Mitarbeitenden

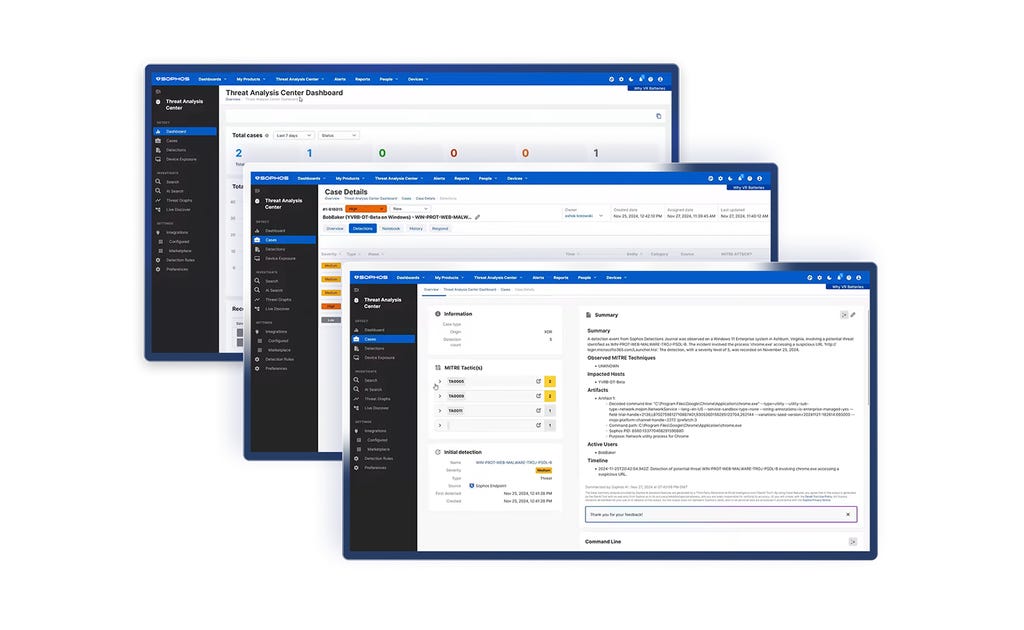

MANAGED DETECTION & RESPONSE

Effektives Beseitigen von Cyberbedrohungen 24/7

Ihre erste, rund um die Uhr aktive Verteidigungslinie – unterstützt durch KI, Threat Intelligence und Experten. Diesem Service vertrauen mehr als 35.000 Unternehmen und Organisationen.

Adaptive AI-Native Cybersecurity Platform

Behalten Sie jede Bedrohung im Griff

Sophos vereint modernste Threat Intelligence, adaptive KI und menschliche Expertise in einer offenen Plattform, um Angriffe zu stoppen, bevor Schaden entsteht.

Sophos Firewall

Jetzt verfügbar: Sophos Firewall v22

Sophos Firewall v22 bringt „Secure by Design“ aufs nächste Level

New Sophos Workspace Protection

Schutz von Remote- und Hybrid-Mitarbeitenden

MANAGED DETECTION & RESPONSE

Effektives Beseitigen von Cyberbedrohungen 24/7

Ihre erste, rund um die Uhr aktive Verteidigungslinie – unterstützt durch KI, Threat Intelligence und Experten. Diesem Service vertrauen mehr als 35.000 Unternehmen und Organisationen.

Modernste Cybersicherheit

Die perfekte Kombination aus erstklassiger Technologie und menschlicher Expertise – optimal abgestimmt auf Ihre Bedürfnisse. So gewinnen Sie auf ganzer Linie.

Starker Schutz und eine adaptive, KI-native Plattform zur frühzeitigen Abwehr von Angriffen

DR-Experten, die Bedrohungen schnell und zuverlässig finden und beseitigen

Einzigartige Abwehrmaßnahmen für die gesamte Angriffsfläche – Endpoint, Firewall, E-Mail und Cloud

Führende Sicherheitsexperten empfehlen Sophos

.webp?width=120&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

.webp?width=440&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

.webp?width=360&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

Stoppen Sie Bedrohungen

frühzeitig

Wir bieten Ihnen innovative KI gegen Bedrohungen und Experten, denen nichts entgeht, damit Sie sich voll und ganz auf Ihr Geschäftswachstum konzentrieren können. Erfahren Sie, wie wir Ihr Unternehmen schützen.

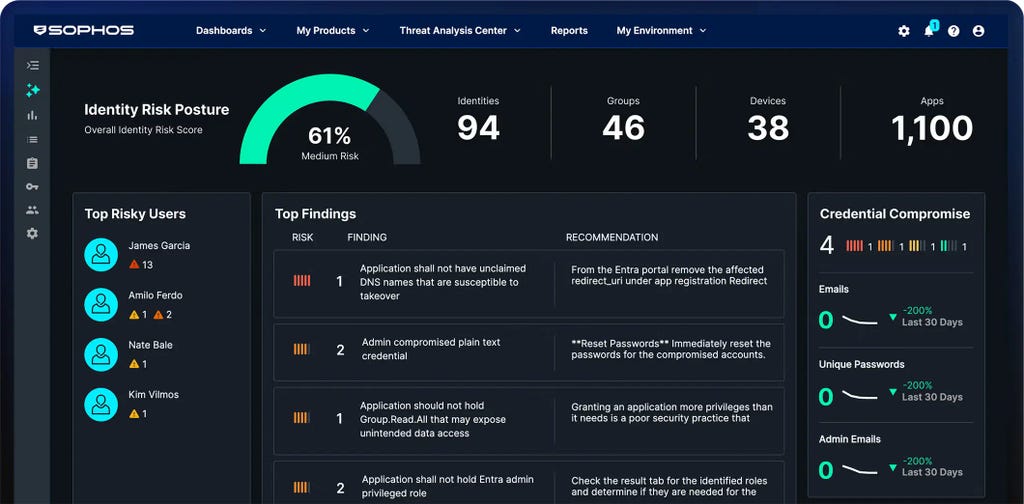

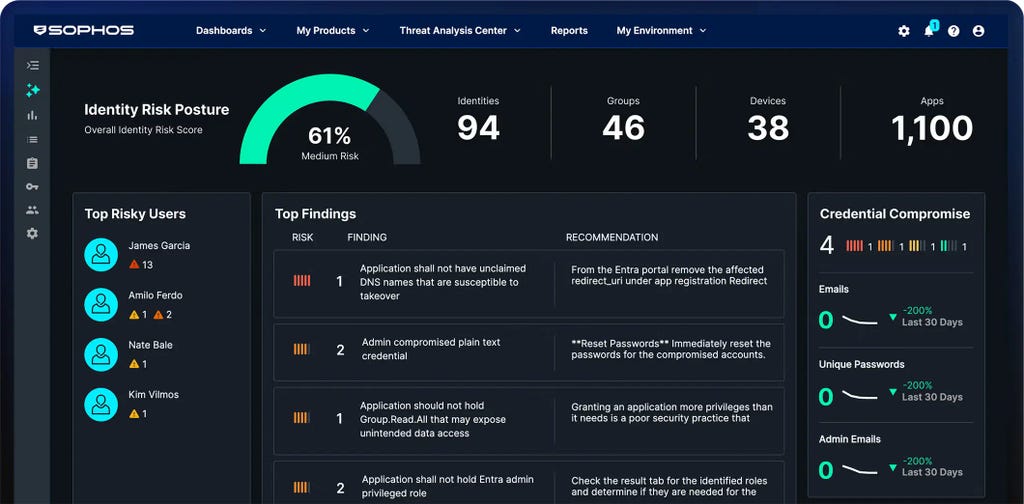

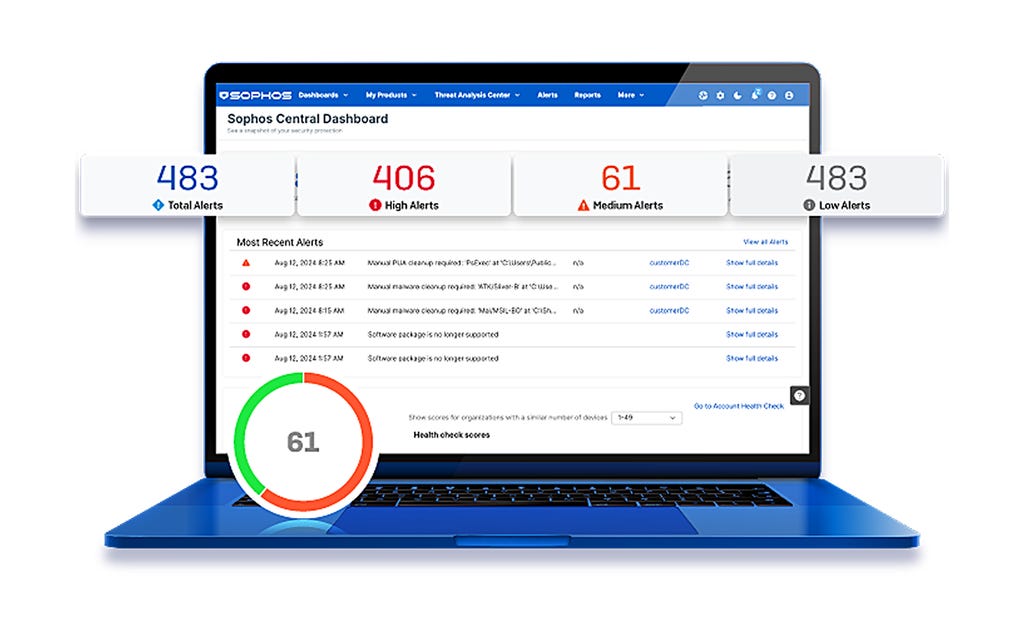

Adaptive, KI-native Cybersecurity-Plattform

Sophos Central bietet Kunden erstklassigen Schutz und sorgt für mehr Effizienz bei der Abwehr. Dynamische Abwehrmaßnahmen, modernste KI und ein offenes Ökosystem mit vielen Integrationen – all das bietet die branchenweit führende KI-Cybersecurity-Plattform.

Mit Sophos sind Sie optimal geschützt

Lösungen für Ihre Sicherheitsprobleme

Wie Unternehmen mit

Sophos sicher bleiben

.webp?width=980&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

Sophos X-Ops

Bietet kollektives Expertenwissen über die gesamte Angriffsumgebung zur effektiven Abwehr hochkomplexer Angreifer.

Events und Training

Informieren Sie sich bei unseren Events und erweitern Sie Ihre Kenntnisse in unseren Trainings – entweder live oder in unseren On-Demand-Webinaren.

.svg?width=185&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

.svg?width=13&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

.png&w=1920&q=75)

.png&w=1920&q=75)

.png&w=1920&q=75)